For the modern mobile phone, see Smartphone.

A mobile phone[a] is a portable telephone that can make and receive calls over a radio frequency link while the user is moving within a telephone service area. The radio frequency link establishes a connection to the switching systems of a mobile phone operator, which provides access to the public switched telephone network (PSTN). Modern mobile telephone services use a cellular network architecture and, therefore, mobile telephones are called cellular telephones or cell phones in North America. In addition to telephony, digital mobile phones (2G) support a variety of other services, such as text messaging, multimedia messagIng, email, Internet access, short-range wireless communications (infrared, Bluetooth), business applications, video games and digital photography. Mobile phones offering only those capabilities are known as feature phones; mobile phones which offer greatly advanced computing capabilities are referred to as smartphones.[1]

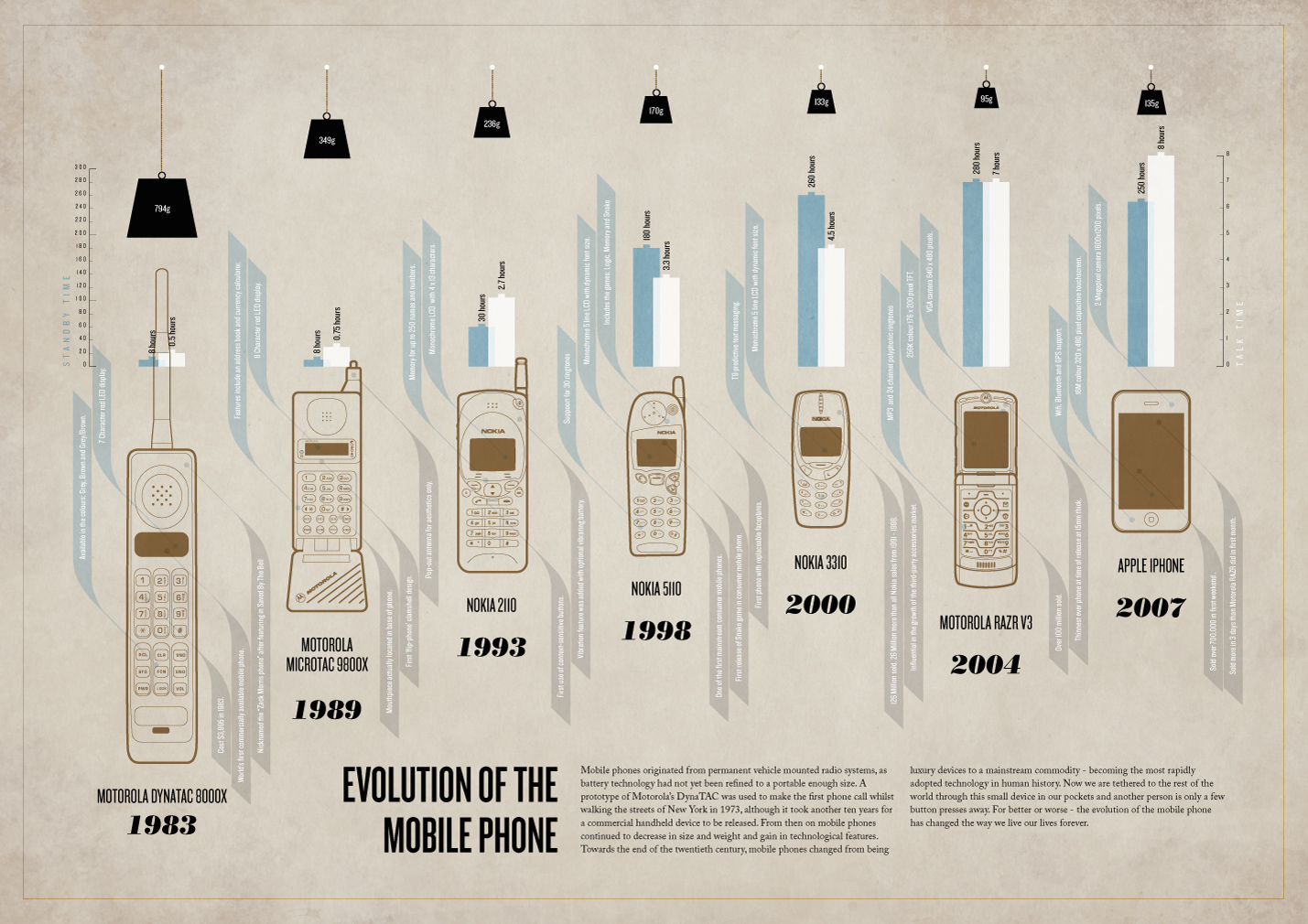

The first handheld mobile phone was demonstrated by Martin Cooper of Motorola in New York City in 1973, using a handset weighing c. 2 kilograms (4.4 lbs).[2] In 1979, Nippon Telegraph and Telephone (NTT) launched the world’s first cellular network in Japan.[3] In 1983, the DynaTAC 8000x was the first commercially available handheld mobile phone. From 1983 to 2014, worldwide mobile phone subscriptions grew to over seven billion; enough to provide one for every person on Earth.[4] In the first quarter of 2016, the top smartphone developers worldwide were Samsung, Apple and Huawei; smartphone sales represented 78 percent of total mobile phone sales.[5] For feature phones (slang: «dumbphones») as of 2016, the top-selling brands were Samsung, Nokia and Alcatel.[6]

Mobile phones are considered an important human invention as it has been one of the most widely used and sold pieces of consumer technology.[7] The growth in popularity has been rapid in some places, for example in the UK the total number of mobile phones overtook the number of houses in 1999.[8] Today mobile phones are globally ubiquitous,[9] and in almost half the world’s countries, over 90% of the population own at least one.[10]

History

Martin Cooper of Motorola, shown here in a 2007 reenactment, made the first publicized handheld mobile phone call on a prototype DynaTAC model on 3 April 1973.

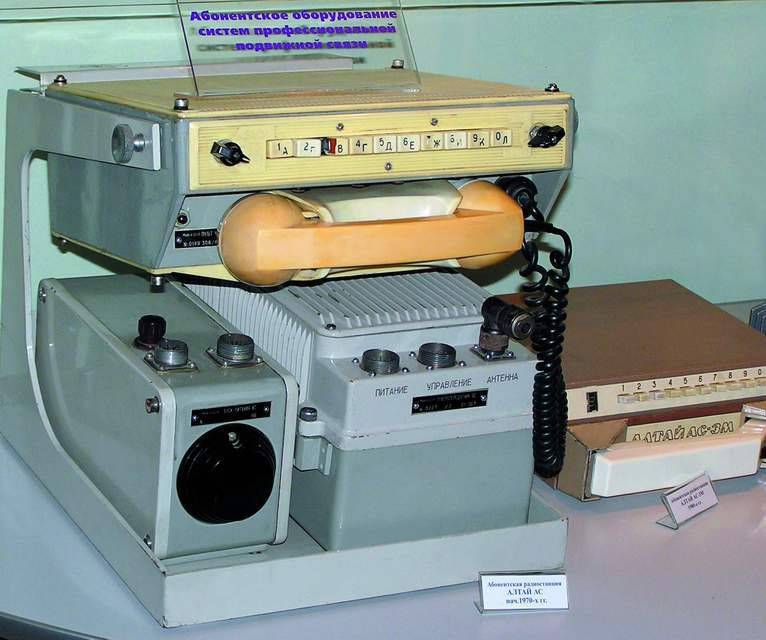

A handheld mobile radio telephone service was envisioned in the early stages of radio engineering. In 1917, Finnish inventor Eric Tigerstedt filed a patent for a «pocket-size folding telephone with a very thin carbon microphone». Early predecessors of cellular phones included analog radio communications from ships and trains. The race to create truly portable telephone devices began after World War II, with developments taking place in many countries. The advances in mobile telephony have been traced in successive «generations», starting with the early zeroth-generation (0G) services, such as Bell System’s Mobile Telephone Service and its successor, the Improved Mobile Telephone Service. These 0G systems were not cellular, supported few simultaneous calls, and were very expensive.

The Motorola DynaTAC 8000X. In 1983, it became the first commercially available handheld cellular mobile phone.

The first handheld cellular mobile phone was demonstrated by John F. Mitchell[11][12] and Martin Cooper of Motorola in 1973, using a handset weighing 2 kilograms (4.4 lb).[2] The first commercial automated cellular network (1G) analog was launched in Japan by Nippon Telegraph and Telephone in 1979. This was followed in 1981 by the simultaneous launch of the Nordic Mobile Telephone (NMT) system in Denmark, Finland, Norway, and Sweden.[13] Several other countries then followed in the early to mid-1980s. These first-generation (1G) systems could support far more simultaneous calls but still used analog cellular technology. In 1983, the DynaTAC 8000x was the first commercially available handheld mobile phone.

In 1991, the second-generation (2G) digital cellular technology was launched in Finland by Radiolinja on the GSM standard. This sparked competition in the sector as the new operators challenged the incumbent 1G network operators. The GSM standard is a European initiative expressed at the CEPT («Conférence Européenne des Postes et Telecommunications», European Postal and Telecommunications conference). The Franco-German R&D cooperation demonstrated the technical feasibility, and in 1987 a Memorandum of Understanding was signed between 13 European countries who agreed to launch a commercial service by 1991. The first version of the GSM (=2G) standard had 6,000 pages. The IEEE and RSE awarded to Thomas Haug and Philippe Dupuis the 2018 James Clerk Maxwell medal for their contributions to the first digital mobile telephone standard.[14] In 2018, the GSM was used by over 5 billion people in over 220 countries. The GSM (2G) has evolved into 3G, 4G and 5G. The standardisation body for GSM started at the CEPT Working Group GSM (Group Special Mobile) in 1982 under the umbrella of CEPT. In 1988, ETSI was established and all CEPT standardization activities were transferred to ETSI. Working Group GSM became Technical Committee GSM. In 1991, it became Technical Committee SMG (Special Mobile Group) when ETSI tasked the committee with UMTS (3G).

Dupuis and Haug during a GSM meeting in Belgium, April 1992

In 2001, the third generation (3G) was launched in Japan by NTT DoCoMo on the WCDMA standard.[15] This was followed by 3.5G, 3G+ or turbo 3G enhancements based on the high-speed packet access (HSPA) family, allowing UMTS networks to have higher data transfer speeds and capacity.

By 2009, it had become clear that, at some point, 3G networks would be overwhelmed by the growth of bandwidth-intensive applications, such as streaming media.[16] Consequently, the industry began looking to data-optimized fourth-generation technologies, with the promise of speed improvements up to ten-fold over existing 3G technologies. The first two commercially available technologies billed as 4G were the WiMAX standard, offered in North America by Sprint, and the LTE standard, first offered in Scandinavia by TeliaSonera.

5G is a technology and term used in research papers and projects to denote the next major phase in mobile telecommunication standards beyond the 4G/IMT-Advanced standards. The term 5G is not officially used in any specification or official document yet made public by telecommunication companies or standardization bodies such as 3GPP, WiMAX Forum or ITU-R. New standards beyond 4G are currently being developed by standardization bodies, but they are at this time seen as under the 4G umbrella, not for a new mobile generation.

Types

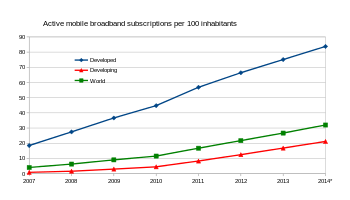

Active mobile broadband subscriptions per 100 inhabitants.[17]

Smartphone

Smartphones have a number of distinguishing features. The International Telecommunication Union measures those with Internet connection, which it calls Active Mobile-Broadband subscriptions (which includes tablets, etc.). In the developed world, smartphones have now overtaken the usage of earlier mobile systems. However, in the developing world, they account for around 50% of mobile telephony.

Feature phone

Feature phone is a term typically used as a retronym to describe mobile phones which are limited in capabilities in contrast to a modern smartphone. Feature phones typically provide voice calling and text messaging functionality, in addition to basic multimedia and Internet capabilities, and other services offered by the user’s wireless service provider. A feature phone has additional functions over and above a basic mobile phone, which is only capable of voice calling and text messaging.[18][19] Feature phones and basic mobile phones tend to use a proprietary, custom-designed software and user interface. By contrast, smartphones generally use a mobile operating system that often shares common traits across devices.

Infrastructure

Cellular networks work by only reusing radio frequencies (in this example frequencies f1-f4) in non adjacent cells to avoid interference

Mobile phones communicate with cell towers that are placed to give coverage across a telephone service area, which is divided up into ‘cells’. Each cell uses a different set of frequencies from neighboring cells, and will typically be covered by three towers placed at different locations. The cell towers are usually interconnected to each other and the phone network and the internet by wired connections. Due to bandwidth limitations each cell will have a maximum number of cell phones it can handle at once. The cells are therefore sized depending on the expected usage density, and may be much smaller in cities. In that case much lower transmitter powers are used to avoid broadcasting beyond the cell.

In order to handle the high traffic, multiple towers can be set up in the same area (using different frequencies). This can be done permanently or temporarily such as at special events like at the Super Bowl, Taste of Chicago, State Fair, NYC New Year’s Eve, hurricane hit cities, etc. where cell phone companies will bring a truck with equipment to host the abnormally high traffic with a portable cell.

Cellular can greatly increase the capacity of simultaneous wireless phone calls. While a phone company for example, has a license to 1,000 frequencies, each cell must use unique frequencies with each call using one of them when communicating. Because cells only slightly overlap, the same frequency can be reused. Example cell one uses frequency 1–500, next door cell uses frequency 501–1,000, next door can reuse frequency 1–500. Cells one and three are not «touching» and do not overlap/communicate so each can reuse the same frequencies.[citation needed]

Capacity was further increased when phone companies implemented digital networks. With digital, one frequency can host multiple simultaneous calls.

As a phone moves around, a phone will «hand off» — automatically disconnect and reconnect to the tower of another cell that gives the best reception.

Additionally, short-range Wi-Fi infrastructure is often used by smartphones as much as possible as it offloads traffic from cell networks on to local area networks.

Hardware

The common components found on all mobile phones are:

- A central processing unit (CPU), the processor of phones. The CPU is a microprocessor fabricated on a metal–oxide–semiconductor (MOS) integrated circuit (IC) chip.

- A battery, providing the power source for the phone functions. A modern handset typically uses a lithium-ion battery (LIB), whereas older handsets used nickel–metal hydride (Ni–MH) batteries.

- An input mechanism to allow the user to interact with the phone. These are a keypad for feature phones, and touch screens for most smartphones (typically with capacitive sensing).

- A display which echoes the user’s typing, and displays text messages, contacts, and more. The display is typically either a liquid-crystal display (LCD) or organic light-emitting diode (OLED) display.

- Speakers for sound.

- Subscriber identity module (SIM) cards and removable user identity module (R-UIM) cards.

- A hardware notification LED on some phones

Low-end mobile phones are often referred to as feature phones and offer basic telephony. Handsets with more advanced computing ability through the use of native software applications are known as smartphones.

Central processing unit

Mobile phones have central processing units (CPUs), similar to those in computers, but optimised to operate in low power environments.

Mobile CPU performance depends not only on the clock rate (generally given in multiples of hertz)[20] but also the memory hierarchy also greatly affects overall performance. Because of these problems, the performance of mobile phone CPUs is often more appropriately given by scores derived from various standardized tests to measure the real effective performance in commonly used applications.

Display

One of the main characteristics of phones is the screen. Depending on the device’s type and design, the screen fills most or nearly all of the space on a device’s front surface. Many smartphone displays have an aspect ratio of 16:9, but taller aspect ratios became more common in 2017.

Screen sizes are often measured in diagonal inches or millimeters; feature phones generally have screen sizes below 90 millimetres (3.5 in). Phones with screens larger than 130 millimetres (5.2 in) are often called «phablets.» Smartphones with screens over 115 millimetres (4.5 in) in size are commonly difficult to use with only a single hand, since most thumbs cannot reach the entire screen surface; they may need to be shifted around in the hand, held in one hand and manipulated by the other, or used in place with both hands. Due to design advances, some modern smartphones with large screen sizes and «edge-to-edge» designs have compact builds that improve their ergonomics, while the shift to taller aspect ratios have resulted in phones that have larger screen sizes whilst maintaining the ergonomics associated with smaller 16:9 displays.[21][22][23]

Liquid-crystal displays are the most common; others are IPS, LED, OLED, and AMOLED displays. Some displays are integrated with pressure-sensitive digitizers, such as those developed by Wacom and Samsung,[24] and Apple’s «3D Touch» system.

Sound

In sound, smartphones and feature phones vary little. Some audio-quality enhancing features, such as Voice over LTE and HD Voice, have appeared and are often available on newer smartphones. Sound quality can remain a problem due to the design of the phone, the quality of the cellular network and compression algorithms used in long-distance calls.[25][26] Audio quality can be improved using a VoIP application over WiFi.[27] Cellphones have small speakers so that the user can use a speakerphone feature and talk to a person on the phone without holding it to their ear. The small speakers can also be used to listen to digital audio files of music or speech or watch videos with an audio component, without holding the phone close to the ear.

Battery

The average phone battery lasts 2–3 years at best. Many of the wireless devices use a Lithium-Ion (Li-Ion) battery, which charges 500–2500 times, depending on how users take care of the battery and the charging techniques used.[28] It is only natural for these rechargeable batteries to chemically age, which is why the performance of the battery when used for a year or two will begin to deteriorate. Battery life can be extended by draining it regularly, not overcharging it, and keeping it away from heat.[29][30]

SIM card

Mobile phones require a small microchip called a Subscriber Identity Module or SIM card, in order to function. The SIM card is approximately the size of a small postage stamp and is usually placed underneath the battery in the rear of the unit. The SIM securely stores the service-subscriber key (IMSI) and the Ki used to identify and authenticate the user of the mobile phone. The SIM card allows users to change phones by simply removing the SIM card from one mobile phone and inserting it into another mobile phone or broadband telephony device, provided that this is not prevented by a SIM lock. The first SIM card was made in 1991 by Munich smart card maker Giesecke & Devrient for the Finnish wireless network operator Radiolinja.[citation needed]

A hybrid mobile phone can hold up to four SIM cards, with a phone having a different device identifier for each SIM Card. SIM and R-UIM cards may be mixed together to allow both GSM and CDMA networks to be accessed. From 2010 onwards, such phones became popular in emerging markets,[31] and this was attributed to the desire to obtain the lowest calling costs.

When the removal of a SIM card is detected by the operating system, it may deny further operation until a reboot.[32]

Software

Software platforms

| This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (October 2018) |

Feature phones have basic software platforms. Smartphones have advanced software platforms. Android OS has been the best-selling OS worldwide on smartphones since 2011.

Mobile app

A mobile app is a computer program designed to run on a mobile device, such as a smartphone. The term «app» is a shortening of the term «software application».

- Messaging

A common data application on mobile phones is Short Message Service (SMS) text messaging. The first SMS message was sent from a computer to a mobile phone in 1992 in the UK while the first person-to-person SMS from phone to phone was sent in Finland in 1993. The first mobile news service, delivered via SMS, was launched in Finland in 2000,[33] and subsequently many organizations provided «on-demand» and «instant» news services by SMS. Multimedia Messaging Service (MMS) was introduced in March 2002.[34]

Application stores

The introduction of Apple’s App Store for the iPhone and iPod Touch in July 2008 popularized manufacturer-hosted online distribution for third-party applications (software and computer programs) focused on a single platform. There are a huge variety of apps, including video games, music products and business tools. Up until that point, smartphone application distribution depended on third-party sources providing applications for multiple platforms, such as GetJar, Handango, Handmark, and PocketGear. Following the success of the App Store, other smartphone manufacturers launched application stores, such as Google’s Android Market (later renamed to the Google Play Store), RIM’s BlackBerry App World, or Android-related app stores like Aptoide, Cafe Bazaar, F-Droid, GetJar, and Opera Mobile Store. In February 2014, 93% of mobile developers were targeting smartphones first for mobile app development.[35]

Sales

By manufacturer

| Rank | Manufacturer | Strategy Analytics report[36] |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Samsung | 21% |

| 2 | Apple | 16% |

| 3 | Xiaomi | 13% |

| 4 | Oppo | 10% |

| 5 | Vivo | 9% |

| Others | 31% | |

| Note: Vendor shipments are branded shipments and exclude OEM sales for all vendors. |

As of 2022, the top five manufacturers worldwide were Samsung (21%), Apple (16%), Xiaomi (13%), Oppo (10%), and Vivo (9%).[37]

- History

From 1983 to 1998, Motorola was market leader in mobile phones. Nokia was the market leader in mobile phones from 1998 to 2012.[38] In Q1 2012, Samsung surpassed Nokia, selling 93.5 million units as against Nokia’s 82.7 million units. Samsung has retained its top position since then.

Aside from Motorola, European brands such as Nokia, Siemens and Ericsson once held large sway over the global mobile phone market, and many new technologies were pioneered in Europe. By 2010, the influence of European companies had significantly decreased due to fierce competition from American and Asian companies, to where most technical innovation had shifted.[39][40] Apple and Google, both of the United States, also came to dominate mobile phone software.[39]

By mobile phone operator

The world’s largest individual mobile operator by number of subscribers is China Mobile, which has over 902 million mobile phone subscribers as of June 2018.[41] Over 50 mobile operators have over ten million subscribers each, and over 150 mobile operators had at least one million subscribers by the end of 2009.[42] In 2014, there were more than seven billion mobile phone subscribers worldwide, a number that is expected to keep growing.

Use

Mobile phone subscribers per 100 inhabitants. 2014 figure is estimated.

Mobile phones are used for a variety of purposes, such as keeping in touch with family members, for conducting business, and in order to have access to a telephone in the event of an emergency. Some people carry more than one mobile phone for different purposes, such as for business and personal use. Multiple SIM cards may be used to take advantage of the benefits of different calling plans. For example, a particular plan might provide for cheaper local calls, long-distance calls, international calls, or roaming.

The mobile phone has been used in a variety of diverse contexts in society. For example:

- A study by Motorola found that one in ten mobile phone subscribers have a second phone that is often kept secret from other family members. These phones may be used to engage in such activities as extramarital affairs or clandestine business dealings.[43]

- Some organizations assist victims of domestic violence by providing mobile phones for use in emergencies. These are often refurbished phones.[44]

- The advent of widespread text-messaging has resulted in the cell phone novel, the first literary genre to emerge from the cellular age, via text messaging to a website that collects the novels as a whole.[45]

- Mobile telephony also facilitates activism and citizen journalism.

- The United Nations reported that mobile phones have spread faster than any other form of technology and can improve the livelihood of the poorest people in developing countries, by providing access to information in places where landlines or the Internet are not available, especially in the least developed countries. Use of mobile phones also spawns a wealth of micro-enterprises, by providing such work as selling airtime on the streets and repairing or refurbishing handsets.[46]

- In Mali and other African countries, people used to travel from village to village to let friends and relatives know about weddings, births, and other events. This can now be avoided in areas with mobile phone coverage, which are usually more extensive than areas with just land-line penetration.

- The TV industry has recently started using mobile phones to drive live TV viewing through mobile apps, advertising, social TV, and mobile TV.[47] It is estimated that 86% of Americans use their mobile phone while watching TV.

- In some parts of the world, mobile phone sharing is common. Cell phone sharing is prevalent in urban India, as families and groups of friends often share one or more mobile phones among their members. There are obvious economic benefits, but often familial customs and traditional gender roles play a part.[48] It is common for a village to have access to only one mobile phone, perhaps owned by a teacher or missionary, which is available to all members of the village for necessary calls.[49]

Content distribution

In 1998, one of the first examples of distributing and selling media content through the mobile phone was the sale of ringtones by Radiolinja in Finland. Soon afterwards, other media content appeared, such as news, video games, jokes, horoscopes, TV content and advertising. Most early content for mobile phones tended to be copies of legacy media, such as banner advertisements or TV news highlight video clips. Recently, unique content for mobile phones has been emerging, from ringtones and ringback tones to mobisodes, video content that has been produced exclusively for mobile phones.[citation needed]

Mobile banking and payment

In many countries, mobile phones are used to provide mobile banking services, which may include the ability to transfer cash payments by secure SMS text message. Kenya’s M-PESA mobile banking service, for example, allows customers of the mobile phone operator Safaricom to hold cash balances which are recorded on their SIM cards. Cash can be deposited or withdrawn from M-PESA accounts at Safaricom retail outlets located throughout the country and can be transferred electronically from person to person and used to pay bills to companies.

Branchless banking has also been successful in South Africa and the Philippines. A pilot project in Bali was launched in 2011 by the International Finance Corporation and an Indonesian bank, Bank Mandiri.[50]

Mobile payments were first trialled in Finland in 1998 when two Coca-Cola vending machines in Espoo were enabled to work with SMS payments. Eventually, the idea spread and in 1999, the Philippines launched the country’s first commercial mobile payments systems with mobile operators Globe and Smart.[citation needed]

Some mobile phones can make mobile payments via direct mobile billing schemes, or through contactless payments if the phone and the point of sale support near field communication (NFC).[51] Enabling contactless payments through NFC-equipped mobile phones requires the co-operation of manufacturers, network operators, and retail merchants.[52][53]

Mobile tracking

Mobile phones are commonly used to collect location data. While the phone is turned on, the geographical location of a mobile phone can be determined easily (whether it is being used or not) using a technique known as multilateration to calculate the differences in time for a signal to travel from the mobile phone to each of several cell towers near the owner of the phone.[54][55]

The movements of a mobile phone user can be tracked by their service provider and, if desired, by law enforcement agencies and their governments. Both the SIM card and the handset can be tracked.[54]

China has proposed using this technology to track the commuting patterns of Beijing city residents.[56] In the UK and US, law enforcement and intelligence services use mobile phones to perform surveillance operations.[57]

Hackers have been able to track a phone’s location, read messages, and record calls, through obtaining a subscribers phone number.[58]

While driving

A driver using two handheld mobile phones at once

A sign in the U.S. restricting cell phone use to certain times of day (no cell phone use between 7:30am-9:00am and 2:00pm-4:15pm)

Mobile phone use while driving, including talking on the phone, texting, or operating other phone features, is common but controversial. It is widely considered dangerous due to distracted driving. Being distracted while operating a motor vehicle has been shown to increase the risk of accidents. In September 2010, the US National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA) reported that 995 people were killed by drivers distracted by cell phones. In March 2011, a U.S. insurance company, State Farm Insurance, announced the results of a study which showed 19% of drivers surveyed accessed the Internet on a smartphone while driving.[59] Many jurisdictions prohibit the use of mobile phones while driving. In Egypt, Israel, Japan, Portugal, and Singapore, both handheld and hands-free use of a mobile phone (which uses a speakerphone) is banned. In other countries, including the UK and France and in many U.S. states, only handheld phone use is banned while hands-free use is permitted.

A 2011 study reported that over 90% of college students surveyed text (initiate, reply or read) while driving.[60]

The scientific literature on the dangers of driving while sending a text message from a mobile phone, or texting while driving, is limited. A simulation study at the University of Utah found a sixfold increase in distraction-related accidents when texting.[61]

Due to the increasing complexity of mobile phones, they are often more like mobile computers in their available uses. This has introduced additional difficulties for law enforcement officials when attempting to distinguish one usage from another in drivers using their devices. This is more apparent in countries which ban both handheld and hands-free usage, rather than those which ban handheld use only, as officials cannot easily tell which function of the mobile phone is being used simply by looking at the driver. This can lead to drivers being stopped for using their device illegally for a phone call when, in fact, they were using the device legally, for example, when using the phone’s incorporated controls for car stereo, GPS or satnav.

A 2010 study reviewed the incidence of mobile phone use while cycling and its effects on behaviour and safety.[62] In 2013, a national survey in the US reported the number of drivers who reported using their cellphones to access the Internet while driving had risen to nearly one of four.[63] A study conducted by the University of Vienna examined approaches for reducing inappropriate and problematic use of mobile phones, such as using mobile phones while driving.[64]

Accidents involving a driver being distracted by talking on a mobile phone have begun to be prosecuted as negligence similar to speeding. In the United Kingdom, from 27 February 2007, motorists who are caught using a hand-held mobile phone while driving will have three penalty points added to their license in addition to the fine of £60.[65] This increase was introduced to try to stem the increase in drivers ignoring the law.[66] Japan prohibits all mobile phone use while driving, including use of hands-free devices. New Zealand has banned hand-held cell phone use since 1 November 2009. Many states in the United States have banned texting on cell phones while driving. Illinois became the 17th American state to enforce this law.[67] As of July 2010, 30 states had banned texting while driving, with Kentucky becoming the most recent addition on 15 July.[68]

Public Health Law Research maintains a list of distracted driving laws in the United States. This database of laws provides a comprehensive view of the provisions of laws that restrict the use of mobile communication devices while driving for all 50 states and the District of Columbia between 1992 when first law was passed, through 1 December 2010. The dataset contains information on 22 dichotomous, continuous or categorical variables including, for example, activities regulated (e.g., texting versus talking, hands-free versus handheld), targeted populations, and exemptions.[69]

In 2010, an estimated 1500 pedestrians were injured in the US while using a cellphone and some jurisdictions have attempted to ban pedestrians from using their cellphones.[70][71]

Health effects

The effect of mobile phone radiation on human health is the subject of recent[when?] interest and study, as a result of the enormous increase in mobile phone usage throughout the world. Mobile phones use electromagnetic radiation in the microwave range, which some believe may be harmful to human health. A large body of research exists, both epidemiological and experimental, in non-human animals and in humans. The majority of this research shows no definite causative relationship between exposure to mobile phones and harmful biological effects in humans. This is often paraphrased simply as the balance of evidence showing no harm to humans from mobile phones, although a significant number of individual studies do suggest such a relationship, or are inconclusive. Other digital wireless systems, such as data communication networks, produce similar radiation.[citation needed]

On 31 May 2011, the World Health Organization stated that mobile phone use may possibly represent a long-term health risk,[72][73] classifying mobile phone radiation as «possibly carcinogenic to humans» after a team of scientists reviewed studies on mobile phone safety.[74] The mobile phone is in category 2B, which ranks it alongside coffee and other possibly carcinogenic substances.[75][76]

Some recent[when?] studies have found an association between mobile phone use and certain kinds of brain and salivary gland tumors. Lennart Hardell and other authors of a 2009 meta-analysis of 11 studies from peer-reviewed journals concluded that cell phone usage for at least ten years «approximately doubles the risk of being diagnosed with a brain tumor on the same (‘ipsilateral’) side of the head as that preferred for cell phone use».[77]

One study of past mobile phone use cited in the report showed a «40% increased risk for gliomas (brain cancer) in the highest category of heavy users (reported average: 30 minutes per day over a 10‐year period)».[78] This is a reversal of the study’s prior position that cancer was unlikely to be caused by cellular phones or their base stations and that reviews had found no convincing evidence for other health effects.[73][79] However, a study published 24 March 2012, in the British Medical Journal questioned these estimates because the increase in brain cancers has not paralleled the increase in mobile phone use.[80] Certain countries, including France, have warned against the use of mobile phones by minors in particular, due to health risk uncertainties.[81] Mobile pollution by transmitting electromagnetic waves can be decreased up to 90% by adopting the circuit as designed in mobile phone and mobile exchange.[82]

In May 2016, preliminary findings of a long-term study by the U.S. government suggested that radio-frequency (RF) radiation, the type emitted by cell phones, can cause cancer.[83][84]

Educational impact

A study by the London School of Economics found that banning mobile phones in schools could increase pupils’ academic performance, providing benefits equal to one extra week of schooling per year.[85]

Electronic waste regulation

Studies have shown that around 40–50% of the environmental impact of mobile phones occurs during the manufacture of their printed wiring boards and integrated circuits.[86]

The average user replaces their mobile phone every 11 to 18 months,[87] and the discarded phones then contribute to electronic waste. Mobile phone manufacturers within Europe are subject to the WEEE directive, and Australia has introduced a mobile phone recycling scheme.[88]

Apple Inc. had an advanced robotic disassembler and sorter called Liam specifically for recycling outdated or broken iPhones.[89]

Theft

According to the Federal Communications Commission, one out of three robberies involve the theft of a cellular phone.[citation needed] Police data in San Francisco show that half of all robberies in 2012 were thefts of cellular phones.[citation needed] An online petition on Change.org, called Secure our Smartphones, urged smartphone manufacturers to install kill switches in their devices to make them unusable if stolen. The petition is part of a joint effort by New York Attorney General Eric Schneiderman and San Francisco District Attorney George Gascón and was directed to the CEOs of the major smartphone manufacturers and telecommunication carriers.[90] On 10 June 2013, Apple announced that it would install a «kill switch» on its next iPhone operating system, due to debut in October 2013.[91]

All mobile phones have a unique identifier called IMEI. Anyone can report their phone as lost or stolen with their Telecom Carrier, and the IMEI would be blacklisted with a central registry.[92] Telecom carriers, depending upon local regulation can or must implement blocking of blacklisted phones in their network. There are, however, a number of ways to circumvent a blacklist. One method is to send the phone to a country where the telecom carriers are not required to implement the blacklisting and sell it there,[93] another involves altering the phone’s IMEI number.[94] Even so, mobile phones typically have less value on the second-hand market if the phones original IMEI is blacklisted.

Conflict minerals

Demand for metals used in mobile phones and other electronics fuelled the Second Congo War, which claimed almost 5.5 million lives.[95] In a 2012 news story, The Guardian reported: «In unsafe mines deep underground in eastern Congo, children are working to extract minerals essential for the electronics industry. The profits from the minerals finance the bloodiest conflict since the second world war; the war has lasted nearly 20 years and has recently flared up again. For the last 15 years, the Democratic Republic of the Congo has been a major source of natural resources for the mobile phone industry.»[96] The company Fairphone has worked to develop a mobile phone that does not contain conflict minerals.[citation needed]

Kosher phones

Due to concerns by the Orthodox Jewish rabbinate in Britain that texting by youths could waste time and lead to «immodest» communication, the rabbinate recommended that phones with text-messaging capability not be used by children; to address this, they gave their official approval to a brand of «Kosher» phones with no texting capabilities. Although these phones are intended to prevent immodesty, some vendors report good sales to adults who prefer the simplicity of the devices; other Orthodox Jews question the need for them.[97]

In Israel, similar phones to kosher phones with restricted features exist to observe the sabbath; under Orthodox Judaism, the use of any electrical device is generally prohibited during this time, other than to save lives, or reduce the risk of death or similar needs. Such phones are approved for use by essential workers, such as health, security, and public service workers.[98]

See also

- Cellular frequencies

- Customer proprietary network information

- Field telephone

- List of countries by number of mobile phones in use

- Mobile broadband

- Mobile Internet device (MID)

- Mobile phone accessories

- Mobile phones on aircraft

- Mobile phone use in schools

- Mobile technology

- Mobile telephony

- Mobile phone form factor

- Optical head-mounted display

- OpenBTS

- Pager

- Personal digital assistant

- Personal Handy-phone System

- Prepaid mobile phone

- Two-way radio

- Professional mobile radio

- Push-button telephone

- Rechargeable battery

- Smombie

- Surveillance

- Tethering

- VoIP phone

Notes

- ^ Also named cellular phone, cell phone, cellphone, handphone, hand phone or pocket phone, sometimes shortened to simply mobile, cell, or just phone.

References

- ^ Srivastava, Viranjay M.; Singh, Ghanshyam (2013). MOSFET Technologies for Double-Pole Four-Throw Radio-Frequency Switch. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 1. ISBN 9783319011653.

- ^ a b Teixeira, Tania (23 April 2010). «Meet the man who invented the mobile phone». BBC News. Retrieved 2 July 2021.

- ^ «Timeline from 1G to 5G: A Brief History on Cell Phones». CENGN. 21 September 2020. Retrieved 18 February 2022.

- ^ «Mobile penetration». 9 July 2010.

Almost 40 percent of the world’s population, 2.7 billion people, are online. The developing world is home to about 826 million female internet users and 980 million male internet users. The developed world is home to about 475 million female Internet users and 483 million male Internet users.

- ^ «Gartner Says Worldwide Smartphone Sales Grew 3.9 Percent in First Quarter of 2016». Gartner. Archived from the original on 22 May 2016. Retrieved 21 May 2016.

- ^ «Nokia Captured 9% Feature Phone Marketshare Worldwide in 2016». Strategyanalytics.com. 24 February 2017. Retrieved 7 September 2018.

- ^ Harris, Arlene; Cooper, Martin (2019). «Mobile phones: Impacts, challenges, and predictions». Human Behavior and Emerging Technologies. 1: 15–17. doi:10.1002/hbe2.112. S2CID 187189041.

- ^ «BBC News | BUSINESS | Mobile phone sales surge».

- ^ Gupta, Gireesh K. (2011). «Ubiquitous mobile phones are becoming indispensable». ACM Inroads. 2 (2): 32–33. doi:10.1145/1963533.1963545. S2CID 2942617.

- ^ «Mobile phones are becoming ubiquitous». International Telecommunication Union (ITU). 17 February 2022.

- ^ «John F. Mitchell Biography». Archived from the original on 23 February 2017. Retrieved 4 October 2012.

- ^ «Who invented the cell phone?». Archived from the original on 23 February 2017. Retrieved 4 October 2012.

- ^ «Swedish National Museum of Science and Technology». Tekniskamuseet.se. Archived from the original on 22 October 2008. Retrieved 29 July 2009.

- ^ «Duke of Cambridge Presents Maxwell Medals to GSM Developers». IEEE United Kingdom and Ireland Section. 1 September 2018. Retrieved 10 December 2020.

- ^ «History of UMTS and 3G Development». Umtsworld.com. Retrieved 29 July 2009.

- ^ Fahd Ahmad Saeed. «Capacity Limit Problem in 3G Networks». Purdue School of Engineering. Retrieved 23 April 2010.

- ^ «Statistics». ITU.

- ^ «feature phone Definition from PC Magazine Encyclopedia». www.pcmag.com.

- ^ Todd Hixon, Two Weeks With A Dumb Phone Archived 30 July 2017 at the Wayback Machine, Forbes, 13 November 2012

- ^ «CPU Frequency». CPU World Glossary. CPU World. 25 March 2008. Retrieved 1 January 2010.

- ^ «Don’t call it a phablet: the 5.5″ Samsung Galaxy S7 Edge is narrower than many 5.2″ devices». PhoneArena. Retrieved 3 April 2017.

- ^ «We’re gonna need Pythagoras’ help to compare screen sizes in 2017». The Verge. 30 March 2017. Retrieved 3 April 2017.

- ^ «The Samsung Galaxy S8 will change the way we think about display sizes». The Verge. Vox Media. 30 March 2017. Retrieved 3 April 2017.

- ^ Ward, J. R.; Phillips, M. J. (1 April 1987). «Digitizer Technology: Performance Characteristics and the Effects on the User Interface». IEEE Computer Graphics and Applications. 7 (4): 31–44. doi:10.1109/MCG.1987.276869. ISSN 0272-1716. S2CID 16707568.

- ^ Jeff Hecht (30 September 2014). «Why Mobile Voice Quality Still Stinks—and How to Fix It». ieee.org.

- ^ Elena Malykhina. «Why Is Cell Phone Call Quality So Terrible?». scientificamerican.com.

- ^ Alan Henry (22 May 2014). «What’s the Best Mobile VoIP App?». Lifehacker. Gawker Media.

- ^ Taylor, Martin. «How To Prolong Your Cell Phone Battery’s Life Span». Phonedog.com. Retrieved 8 June 2018.

- ^ «Iphone Battery and Performance». Apple Support. Retrieved 8 June 2018.

- ^ Hill, Simon. «Should You Leave Your Smartphone Plugged Into The Charger Overnight? We Asked An Expert». Digital Trends. Retrieved 8 June 2018.

- ^ «Smartphone boom lifts phone market in first quarter». Reuters. 29 April 2011. Archived from the original on 8 May 2011. Retrieved 6 May 2019.

- ^ «How to Fix ‘No SIM Card Detected’ Error on Android». Make Tech Easier. 20 September 2020.

- ^ Lynn, Natalie (10 March 2016). «The History and Evolution of Mobile Advertising». Gimbal. Retrieved 3 October 2021.

- ^ Bodic, Gwenaël Le (8 July 2005). Mobile Messaging Technologies and Services: SMS, EMS and MMS. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-0-470-01451-6.

- ^ W3C Interview: Vision Mobile on the App Developer Economy with Matos Kapetanakis and Dimitris Michalakos Archived 29 June 2016 at the Wayback Machine. 18 February 2014. Retrieved 24 February 2015.

- ^ «Global Smartphone Market Share: By Quarter». Counterpoint Research. 24 August 2022. Retrieved 28 August 2022.

- ^ «Global Smartphone Market Share: By Quarter». Counterpoint Research. 24 August 2022. Retrieved 28 August 2022.

- ^ Cheng, Roger. «Farewell Nokia: The rise and fall of a mobile pioneer». CNET.

- ^ a b «How the smartphone made Europe look stupid». the Guardian. 14 February 2010.

- ^ Mobility, Yomi Adegboye AKA Mister (5 February 2020). «Non-Chinese smartphones: These phones are not made in China — MobilityArena.com». mobilityarena.com.

- ^ «Operation Data». China Mobile. 31 August 2017.

- ^ Source: wireless intelligence

- ^ «Millions keep secret mobile». BBC News. 16 October 2001. Retrieved 4 November 2009.

- ^ Brooks, Richard (13 August 2007). «Donated cell phones help battered women». The Press-Enterprise. Archived from the original on 25 September 2009. Retrieved 4 November 2009.

- ^ Goodyear, Dana (7 January 2009). «Letter from Japan: I ♥ Novels». The New Yorker. Retrieved 29 July 2009.

- ^ Lynn, Jonathan. «Mobile phones help lift poor out of poverty: U.N. study». Reuters. Retrieved 3 December 2013.

- ^ «4 Ways Smartphones Can Save Live TV». Tvgenius.net. Archived from the original on 14 May 2012. Retrieved 4 June 2012.

- ^ Donner, Jonathan, and Steenson, Molly Wright. «Beyond the Personal and Private: Modes of Mobile Phone Sharing in Urban India.» In The Reconstruction of Space and Time: Mobile Communication Practices, edited by Scott Campbell and Rich Ling, 231–50. Piscataway, NJ: Transaction Publishers, 2008.

- ^ Hahn, Hans; Kibora, Ludovic (2008). «The Domestication of the Mobile Phone: Oral Society and New ICT in Burkina Faso». Journal of Modern African Studies. 46: 87–109. doi:10.1017/s0022278x07003084. S2CID 154804246.

- ^ «Branchless banking to start in Bali». The Jakarta Post. 13 April 2012. Retrieved 4 June 2012.

- ^ Feig, Nancy (25 June 2007). «Mobile Payments: Look to Korea». banktech.com. Archived from the original on 26 March 2010. Retrieved 29 January 2011.

- ^ Ready, Sarah (10 November 2009). «NFC mobile phone set to explode». connectedplanetonline.com. Archived from the original on 24 January 2010. Retrieved 29 January 2011.

- ^ Tofel, Kevin C. (20 August 2010). «VISA Testing NFC Memory Cards for Wireless Payments». gigaom.com. Archived from the original on 21 June 2012. Retrieved 21 January 2011.

- ^ a b «Tracking a suspect by mobile phone». BBC News. 3 August 2005. Retrieved 14 March 2009.

- ^ Miller, Joshua (14 March 2009). «Cell Phone Tracking Can Locate Terrorists — But Only Where It’s Legal». FOX News. Retrieved 4 February 2014.

- ^ Cecilia Kang (3 March 2011). «China plans to track cellphone users, sparking human rights concerns». The Washington Post.

- ^ McCullagh, Declan; Anne Broache (1 December 2006). «FBI taps cell phone mic as eavesdropping tool». CNet News. Archived from the original on 10 November 2013. Retrieved 14 March 2009.

- ^ Gibbs, Samuel (18 April 2016). «Your phone number is all a hacker needs to read texts, listen to calls and track you» – via www.theguardian.com.

- ^ «Quit Googling yourself and drive: About 20% of drivers using Web behind the wheel, study says». Los Angeles Times. 4 March 2011.

- ^ Atchley, Paul; Atwood, Stephanie; Boulton, Aaron (January 2011). «The Choice to Text and Drive in Younger Drivers: Behaviour May Shape Attitude». Accident Analysis and Prevention. 43 (1): 134–142. doi:10.1016/j.aap.2010.08.003. PMID 21094307.

- ^ «Text messaging not illegal but data clear on its peril». Democrat and Chronicle. Archived from the original on 29 April 2008.

- ^ de Waard, D., Schepers, P., Ormel, W. and Brookhuis, K., 2010, Mobile phone use while cycling: Incidence and effects on behaviour and safety, Ergonomics, Vol 53, No. 1, January 2010, pp. 30–42.

- ^ «Drivers still Web surfing while driving, survey finds». USA TODAY.

- ^ Burger, Christoph; Riemer, Valentin; Grafeneder, Jürgen; Woisetschläger, Bianca; Vidovic, Dragana; Hergovich, Andreas (2010). «Reaching the Mobile Respondent: Determinants of High-Level Mobile Phone Use Among a High-Coverage Group» (PDF). Social Science Computer Review. 28 (3): 336–349. doi:10.1177/0894439309353099. S2CID 61640965.

- ^ «Drivers face new phone penalties». 22 January 2007 – via news.bbc.co.uk.

- ^ «Careless talk». 22 February 2007 – via news.bbc.co.uk.

- ^ «Illinois to ban texting while driving». CNN. 6 August 2009. Retrieved 12 May 2010.

- ^ Steitzer, Stephanie (14 July 2010). «Texting while driving ban, other new Kentucky laws take effect today». The Courier-Journal. Archived from the original on 19 January 2013. Retrieved 15 July 2010.

- ^ «Distracted Driving Laws». Public Health Law Research. 15 July 2011. Retrieved 27 June 2014.

- ^ Nasar, Jack L.; Troyer, Dereck (21 March 2013). «Pedestrian injuries due to mobile phone use in public places» (PDF). Accident Analysis and Prevention. 57: 91–95. doi:10.1016/j.aap.2013.03.021. PMID 23644536. S2CID 8743434. Archived from the original (PDF) on 31 July 2017. Retrieved 31 July 2017.

- ^ Grabar, Henry (28 July 2017). «The Absurdity of Honolulu’s New Law Banning Pedestrians From Looking at Their Cellphones». Slate. Retrieved 31 July 2017.

- ^ «IARC Classifies Radiofrequency Electromagnetic Fields as Possibly Carcinogenic to Humans» (PDF). World Health Organization.

- ^ a b «What are the health risks associated with mobile phones and their base stations?». Online Q&A. World Health Organization. 5 December 2005. Retrieved 19 January 2008.

- ^ «WHO: Cell phone use can increase possible cancer risk». CNN. 31 May 2011. Retrieved 31 May 2011.

- ^ «Agents Classified by the IARC Monographs, Volumes 1–107» (PDF). monographs.iarc.fr. Archived from the original (PDF) on 25 October 2011. Retrieved 5 March 2013.

- ^ Kovvali, Gopala (1 January 2011). «Cell phones are as carcinogenic as coffee». Journal of Carcinogenesis. 10 (1): 18. doi:10.4103/1477-3163.83044. PMC 3142790. PMID 21799662.

- ^ Khurana, VG; Teo C; Kundi M; Hardell L; Carlberg M (2009). «Cell phones and brain tumors: A review including the long term epidemiologic data». Surgical Neurology. 72 (3): 205–214. doi:10.1016/j.surneu.2009.01.019. PMID 19328536.

- ^ «World Health Organization: Cell Phones May Cause Cancer». Business Insider. Retrieved 31 May 2011.

- ^ «Electromagnetic fields and public health: mobile telephones and their base stations». Fact sheet N°193. World Health Organization. June 2000. Archived from the original on 27 February 2004. Retrieved 19 January 2008.

- ^ Little MP, Rajaraman P, Curtis RE, et al. (2012). «Mobile phone use and glioma risk: comparison of epidemiological study results with incidence trends in the United States». BMJ. 344: e1147. doi:10.1136/bmj.e1147. PMC 3297541. PMID 22403263.

- ^ Brian Rohan (2 January 2008). «France warns against excessive mobile phone use». Reuters. Retrieved 10 May 2010.

- ^ Bhattacharjee, Pijush Kanti (2012). «Mobile Phone and System Are Designed In A Novel Way To Have Minimum Electromagnetic Wave Transmission In Air and Minimum Electrical Power Consumption» (PDF). International Journal of Computer Networks and Wireless Communications [IJCNWC]. 2 (5): 556–559.

- ^ Harkinson, Josh (27 May 2016). ««Game-changing» study links cellphone radiation to cancer». Mother Jones. Retrieved 10 December 2020.

- ^ ««Report of Partial Findings from the National Toxicology Program Carcinogenesis Studies of Cell Phone Radiofrequency Radiation in Hsd: Sprague Dawley® SD rats (Whole Body Exposures) – Draft 5-19-2016»» (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 1 June 2016. Retrieved 27 May 2016.

- ^ Davis, Anna (18 May 2015). «Social media ‘more stressful than exams’«. London Evening Standard. p. 13.

- ^ «The Secret Life Series – Environmental Impacts of Cell Phones». Inform, Inc. Retrieved 4 February 2014.

- ^ «E-waste research group, Facts and figures». Griffith University. Retrieved 3 December 2011.

- ^ «Mobile Phone Waste and The Environment». Aussie Recycling Program. Retrieved 3 December 2011.

- ^ Rujanavech, Charissa; Lessard, Joe; Chandler, Sarah; Shannon, Sean; Dahmus, Jeffrey; Guzzo, Rob (September 2016). «Liam — An Innovation Story» (PDF). Apple. Retrieved 10 May 2022.

- ^ Adams, Mike «Plea Urges Anti-Theft Phone Tech» Archived 16 October 2014 at the Wayback Machine San Francisco Examiner 7 June 2013 p. 5

- ^ «Apple to add kill switches to help combat iPhone theft» by Jaxon Van Derbeken San Francisco Chronicle 11 June 2013 p. 1

- ^ «IMEIpro – free IMEI number check service». www.imeipro.info. Retrieved 29 September 2016.

- ^ «How stolen phone blacklists will tamp down on crime, and what to do in the mean time». 27 November 2012. Retrieved 29 September 2016.

- ^ «How To Change IMEI Number». 1 July 2015. Retrieved 29 September 2016.

- ^ «Is your mobile phone helping fund war in Congo?». The Daily Telegraph. 27 September 2011. Archived from the original on 10 January 2022.

- ^ «Children of the Congo who risk their lives to supply our mobile phones». The Guardian. 7 December 2012.

- ^ Brunwasser, Matthew (25 January 2012). «Kosher Phones For Britain’s Orthodox Jews». Public Radio International.

- ^ Hirshfeld, Rachel (26 March 2012). «Introducing: A ‘Kosher Phone’ Permitted on Shabbat». Arutz Sheva.

Further reading

- Agar, Jon, Constant Touch: A Global History of the Mobile Phone, 2004 ISBN 1-84046-541-7

- Fessenden, R. A. (1908). «Wireless Telephony». Annual Report of the Board of Regents of the Smithsonian Institution. The Institution: 161–196. Retrieved 7 August 2009.

- Glotz, Peter & Bertsch, Stefan, eds. Thumb Culture: The Meaning of Mobile Phones for Society, 2005

- Goggin, Gerard, Global Mobile Media (New York: Routledge, 2011), p. 176. ISBN 978-0-415-46918-0

- Jain, S. Lochlann (2002). «Urban Errands: The Means of Mobility». Journal of Consumer Culture. 2: 385–404. doi:10.1177/146954050200200305. S2CID 145577892.

- Katz, James E. & Aakhus, Mark, eds. Perpetual Contact: Mobile Communication, Private Talk, Public Performance, 2002

- Kavoori, Anandam & Arceneaux, Noah, eds. The Cell Phone Reader: Essays in Social Transformation, 2006

- Kennedy, Pagan. Who Made That Cellphone? Archived 4 November 2017 at the Wayback Machine, The New York Times, 15 March 2013, p. MM19

- Kopomaa, Timo. The City in Your Pocket, Gaudeamus 2000

- Levinson, Paul, Cellphone: The Story of the World’s Most Mobile Medium, and How It Has Transformed Everything!, 2004 ISBN 1-4039-6041-0

- Ling, Rich, The Mobile Connection: the Cell Phone’s Impact on Society, 2004 ISBN 1-55860-936-9

- Ling, Rich and Pedersen, Per, eds. Mobile Communications: Re-negotiation of the Social Sphere, 2005 ISBN 1-85233-931-4

- Home page of Rich Ling

- Nyíri, Kristóf, ed. Mobile Communication: Essays on Cognition and Community, 2003

- Nyíri, Kristóf, ed. Mobile Learning: Essays on Philosophy, Psychology and Education, 2003

- Nyíri, Kristóf, ed. Mobile Democracy: Essays on Society, Self and Politics, 2003

- Nyíri, Kristóf, ed. A Sense of Place: The Global and the Local in Mobile Communication, 2005

- Nyíri, Kristóf, ed. Mobile Understanding: The Epistemology of Ubiquitous Communication, 2006

- Plant, Dr. Sadie, on the mobile – the effects of mobile telephones on social and individual life, 2001

- Rheingold, Howard, Smart Mobs: The Next Social Revolution, 2002 ISBN 0-7382-0861-2

- Singh, Rohit (April 2009). Mobile phones for development and profit: a win-win scenario (PDF). Overseas Development Institute. p. 2. Archived from the original (PDF) on 16 April 2009. Retrieved 5 April 2009.

External links

- «How Cell Phones Work» at HowStuffWorks

- «The Long Odyssey of the Cell Phone», 15 photos with captions from Time magazine

- Cell Phone, the ring heard around the world—a video documentary by the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation

For the modern mobile phone, see Smartphone.

A mobile phone[a] is a portable telephone that can make and receive calls over a radio frequency link while the user is moving within a telephone service area. The radio frequency link establishes a connection to the switching systems of a mobile phone operator, which provides access to the public switched telephone network (PSTN). Modern mobile telephone services use a cellular network architecture and, therefore, mobile telephones are called cellular telephones or cell phones in North America. In addition to telephony, digital mobile phones (2G) support a variety of other services, such as text messaging, multimedia messagIng, email, Internet access, short-range wireless communications (infrared, Bluetooth), business applications, video games and digital photography. Mobile phones offering only those capabilities are known as feature phones; mobile phones which offer greatly advanced computing capabilities are referred to as smartphones.[1]

The first handheld mobile phone was demonstrated by Martin Cooper of Motorola in New York City in 1973, using a handset weighing c. 2 kilograms (4.4 lbs).[2] In 1979, Nippon Telegraph and Telephone (NTT) launched the world’s first cellular network in Japan.[3] In 1983, the DynaTAC 8000x was the first commercially available handheld mobile phone. From 1983 to 2014, worldwide mobile phone subscriptions grew to over seven billion; enough to provide one for every person on Earth.[4] In the first quarter of 2016, the top smartphone developers worldwide were Samsung, Apple and Huawei; smartphone sales represented 78 percent of total mobile phone sales.[5] For feature phones (slang: «dumbphones») as of 2016, the top-selling brands were Samsung, Nokia and Alcatel.[6]

Mobile phones are considered an important human invention as it has been one of the most widely used and sold pieces of consumer technology.[7] The growth in popularity has been rapid in some places, for example in the UK the total number of mobile phones overtook the number of houses in 1999.[8] Today mobile phones are globally ubiquitous,[9] and in almost half the world’s countries, over 90% of the population own at least one.[10]

History

Martin Cooper of Motorola, shown here in a 2007 reenactment, made the first publicized handheld mobile phone call on a prototype DynaTAC model on 3 April 1973.

A handheld mobile radio telephone service was envisioned in the early stages of radio engineering. In 1917, Finnish inventor Eric Tigerstedt filed a patent for a «pocket-size folding telephone with a very thin carbon microphone». Early predecessors of cellular phones included analog radio communications from ships and trains. The race to create truly portable telephone devices began after World War II, with developments taking place in many countries. The advances in mobile telephony have been traced in successive «generations», starting with the early zeroth-generation (0G) services, such as Bell System’s Mobile Telephone Service and its successor, the Improved Mobile Telephone Service. These 0G systems were not cellular, supported few simultaneous calls, and were very expensive.

The Motorola DynaTAC 8000X. In 1983, it became the first commercially available handheld cellular mobile phone.

The first handheld cellular mobile phone was demonstrated by John F. Mitchell[11][12] and Martin Cooper of Motorola in 1973, using a handset weighing 2 kilograms (4.4 lb).[2] The first commercial automated cellular network (1G) analog was launched in Japan by Nippon Telegraph and Telephone in 1979. This was followed in 1981 by the simultaneous launch of the Nordic Mobile Telephone (NMT) system in Denmark, Finland, Norway, and Sweden.[13] Several other countries then followed in the early to mid-1980s. These first-generation (1G) systems could support far more simultaneous calls but still used analog cellular technology. In 1983, the DynaTAC 8000x was the first commercially available handheld mobile phone.

In 1991, the second-generation (2G) digital cellular technology was launched in Finland by Radiolinja on the GSM standard. This sparked competition in the sector as the new operators challenged the incumbent 1G network operators. The GSM standard is a European initiative expressed at the CEPT («Conférence Européenne des Postes et Telecommunications», European Postal and Telecommunications conference). The Franco-German R&D cooperation demonstrated the technical feasibility, and in 1987 a Memorandum of Understanding was signed between 13 European countries who agreed to launch a commercial service by 1991. The first version of the GSM (=2G) standard had 6,000 pages. The IEEE and RSE awarded to Thomas Haug and Philippe Dupuis the 2018 James Clerk Maxwell medal for their contributions to the first digital mobile telephone standard.[14] In 2018, the GSM was used by over 5 billion people in over 220 countries. The GSM (2G) has evolved into 3G, 4G and 5G. The standardisation body for GSM started at the CEPT Working Group GSM (Group Special Mobile) in 1982 under the umbrella of CEPT. In 1988, ETSI was established and all CEPT standardization activities were transferred to ETSI. Working Group GSM became Technical Committee GSM. In 1991, it became Technical Committee SMG (Special Mobile Group) when ETSI tasked the committee with UMTS (3G).

Dupuis and Haug during a GSM meeting in Belgium, April 1992

In 2001, the third generation (3G) was launched in Japan by NTT DoCoMo on the WCDMA standard.[15] This was followed by 3.5G, 3G+ or turbo 3G enhancements based on the high-speed packet access (HSPA) family, allowing UMTS networks to have higher data transfer speeds and capacity.

By 2009, it had become clear that, at some point, 3G networks would be overwhelmed by the growth of bandwidth-intensive applications, such as streaming media.[16] Consequently, the industry began looking to data-optimized fourth-generation technologies, with the promise of speed improvements up to ten-fold over existing 3G technologies. The first two commercially available technologies billed as 4G were the WiMAX standard, offered in North America by Sprint, and the LTE standard, first offered in Scandinavia by TeliaSonera.

5G is a technology and term used in research papers and projects to denote the next major phase in mobile telecommunication standards beyond the 4G/IMT-Advanced standards. The term 5G is not officially used in any specification or official document yet made public by telecommunication companies or standardization bodies such as 3GPP, WiMAX Forum or ITU-R. New standards beyond 4G are currently being developed by standardization bodies, but they are at this time seen as under the 4G umbrella, not for a new mobile generation.

Types

Active mobile broadband subscriptions per 100 inhabitants.[17]

Smartphone

Smartphones have a number of distinguishing features. The International Telecommunication Union measures those with Internet connection, which it calls Active Mobile-Broadband subscriptions (which includes tablets, etc.). In the developed world, smartphones have now overtaken the usage of earlier mobile systems. However, in the developing world, they account for around 50% of mobile telephony.

Feature phone

Feature phone is a term typically used as a retronym to describe mobile phones which are limited in capabilities in contrast to a modern smartphone. Feature phones typically provide voice calling and text messaging functionality, in addition to basic multimedia and Internet capabilities, and other services offered by the user’s wireless service provider. A feature phone has additional functions over and above a basic mobile phone, which is only capable of voice calling and text messaging.[18][19] Feature phones and basic mobile phones tend to use a proprietary, custom-designed software and user interface. By contrast, smartphones generally use a mobile operating system that often shares common traits across devices.

Infrastructure

Cellular networks work by only reusing radio frequencies (in this example frequencies f1-f4) in non adjacent cells to avoid interference

Mobile phones communicate with cell towers that are placed to give coverage across a telephone service area, which is divided up into ‘cells’. Each cell uses a different set of frequencies from neighboring cells, and will typically be covered by three towers placed at different locations. The cell towers are usually interconnected to each other and the phone network and the internet by wired connections. Due to bandwidth limitations each cell will have a maximum number of cell phones it can handle at once. The cells are therefore sized depending on the expected usage density, and may be much smaller in cities. In that case much lower transmitter powers are used to avoid broadcasting beyond the cell.

In order to handle the high traffic, multiple towers can be set up in the same area (using different frequencies). This can be done permanently or temporarily such as at special events like at the Super Bowl, Taste of Chicago, State Fair, NYC New Year’s Eve, hurricane hit cities, etc. where cell phone companies will bring a truck with equipment to host the abnormally high traffic with a portable cell.

Cellular can greatly increase the capacity of simultaneous wireless phone calls. While a phone company for example, has a license to 1,000 frequencies, each cell must use unique frequencies with each call using one of them when communicating. Because cells only slightly overlap, the same frequency can be reused. Example cell one uses frequency 1–500, next door cell uses frequency 501–1,000, next door can reuse frequency 1–500. Cells one and three are not «touching» and do not overlap/communicate so each can reuse the same frequencies.[citation needed]

Capacity was further increased when phone companies implemented digital networks. With digital, one frequency can host multiple simultaneous calls.

As a phone moves around, a phone will «hand off» — automatically disconnect and reconnect to the tower of another cell that gives the best reception.

Additionally, short-range Wi-Fi infrastructure is often used by smartphones as much as possible as it offloads traffic from cell networks on to local area networks.

Hardware

The common components found on all mobile phones are:

- A central processing unit (CPU), the processor of phones. The CPU is a microprocessor fabricated on a metal–oxide–semiconductor (MOS) integrated circuit (IC) chip.

- A battery, providing the power source for the phone functions. A modern handset typically uses a lithium-ion battery (LIB), whereas older handsets used nickel–metal hydride (Ni–MH) batteries.

- An input mechanism to allow the user to interact with the phone. These are a keypad for feature phones, and touch screens for most smartphones (typically with capacitive sensing).

- A display which echoes the user’s typing, and displays text messages, contacts, and more. The display is typically either a liquid-crystal display (LCD) or organic light-emitting diode (OLED) display.

- Speakers for sound.

- Subscriber identity module (SIM) cards and removable user identity module (R-UIM) cards.

- A hardware notification LED on some phones

Low-end mobile phones are often referred to as feature phones and offer basic telephony. Handsets with more advanced computing ability through the use of native software applications are known as smartphones.

Central processing unit

Mobile phones have central processing units (CPUs), similar to those in computers, but optimised to operate in low power environments.

Mobile CPU performance depends not only on the clock rate (generally given in multiples of hertz)[20] but also the memory hierarchy also greatly affects overall performance. Because of these problems, the performance of mobile phone CPUs is often more appropriately given by scores derived from various standardized tests to measure the real effective performance in commonly used applications.

Display

One of the main characteristics of phones is the screen. Depending on the device’s type and design, the screen fills most or nearly all of the space on a device’s front surface. Many smartphone displays have an aspect ratio of 16:9, but taller aspect ratios became more common in 2017.

Screen sizes are often measured in diagonal inches or millimeters; feature phones generally have screen sizes below 90 millimetres (3.5 in). Phones with screens larger than 130 millimetres (5.2 in) are often called «phablets.» Smartphones with screens over 115 millimetres (4.5 in) in size are commonly difficult to use with only a single hand, since most thumbs cannot reach the entire screen surface; they may need to be shifted around in the hand, held in one hand and manipulated by the other, or used in place with both hands. Due to design advances, some modern smartphones with large screen sizes and «edge-to-edge» designs have compact builds that improve their ergonomics, while the shift to taller aspect ratios have resulted in phones that have larger screen sizes whilst maintaining the ergonomics associated with smaller 16:9 displays.[21][22][23]

Liquid-crystal displays are the most common; others are IPS, LED, OLED, and AMOLED displays. Some displays are integrated with pressure-sensitive digitizers, such as those developed by Wacom and Samsung,[24] and Apple’s «3D Touch» system.

Sound

In sound, smartphones and feature phones vary little. Some audio-quality enhancing features, such as Voice over LTE and HD Voice, have appeared and are often available on newer smartphones. Sound quality can remain a problem due to the design of the phone, the quality of the cellular network and compression algorithms used in long-distance calls.[25][26] Audio quality can be improved using a VoIP application over WiFi.[27] Cellphones have small speakers so that the user can use a speakerphone feature and talk to a person on the phone without holding it to their ear. The small speakers can also be used to listen to digital audio files of music or speech or watch videos with an audio component, without holding the phone close to the ear.

Battery

The average phone battery lasts 2–3 years at best. Many of the wireless devices use a Lithium-Ion (Li-Ion) battery, which charges 500–2500 times, depending on how users take care of the battery and the charging techniques used.[28] It is only natural for these rechargeable batteries to chemically age, which is why the performance of the battery when used for a year or two will begin to deteriorate. Battery life can be extended by draining it regularly, not overcharging it, and keeping it away from heat.[29][30]

SIM card

Mobile phones require a small microchip called a Subscriber Identity Module or SIM card, in order to function. The SIM card is approximately the size of a small postage stamp and is usually placed underneath the battery in the rear of the unit. The SIM securely stores the service-subscriber key (IMSI) and the Ki used to identify and authenticate the user of the mobile phone. The SIM card allows users to change phones by simply removing the SIM card from one mobile phone and inserting it into another mobile phone or broadband telephony device, provided that this is not prevented by a SIM lock. The first SIM card was made in 1991 by Munich smart card maker Giesecke & Devrient for the Finnish wireless network operator Radiolinja.[citation needed]

A hybrid mobile phone can hold up to four SIM cards, with a phone having a different device identifier for each SIM Card. SIM and R-UIM cards may be mixed together to allow both GSM and CDMA networks to be accessed. From 2010 onwards, such phones became popular in emerging markets,[31] and this was attributed to the desire to obtain the lowest calling costs.

When the removal of a SIM card is detected by the operating system, it may deny further operation until a reboot.[32]

Software

Software platforms

| This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (October 2018) |

Feature phones have basic software platforms. Smartphones have advanced software platforms. Android OS has been the best-selling OS worldwide on smartphones since 2011.

Mobile app

A mobile app is a computer program designed to run on a mobile device, such as a smartphone. The term «app» is a shortening of the term «software application».

- Messaging

A common data application on mobile phones is Short Message Service (SMS) text messaging. The first SMS message was sent from a computer to a mobile phone in 1992 in the UK while the first person-to-person SMS from phone to phone was sent in Finland in 1993. The first mobile news service, delivered via SMS, was launched in Finland in 2000,[33] and subsequently many organizations provided «on-demand» and «instant» news services by SMS. Multimedia Messaging Service (MMS) was introduced in March 2002.[34]

Application stores

The introduction of Apple’s App Store for the iPhone and iPod Touch in July 2008 popularized manufacturer-hosted online distribution for third-party applications (software and computer programs) focused on a single platform. There are a huge variety of apps, including video games, music products and business tools. Up until that point, smartphone application distribution depended on third-party sources providing applications for multiple platforms, such as GetJar, Handango, Handmark, and PocketGear. Following the success of the App Store, other smartphone manufacturers launched application stores, such as Google’s Android Market (later renamed to the Google Play Store), RIM’s BlackBerry App World, or Android-related app stores like Aptoide, Cafe Bazaar, F-Droid, GetJar, and Opera Mobile Store. In February 2014, 93% of mobile developers were targeting smartphones first for mobile app development.[35]

Sales

By manufacturer

| Rank | Manufacturer | Strategy Analytics report[36] |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Samsung | 21% |

| 2 | Apple | 16% |

| 3 | Xiaomi | 13% |

| 4 | Oppo | 10% |

| 5 | Vivo | 9% |

| Others | 31% | |

| Note: Vendor shipments are branded shipments and exclude OEM sales for all vendors. |

As of 2022, the top five manufacturers worldwide were Samsung (21%), Apple (16%), Xiaomi (13%), Oppo (10%), and Vivo (9%).[37]

- History

From 1983 to 1998, Motorola was market leader in mobile phones. Nokia was the market leader in mobile phones from 1998 to 2012.[38] In Q1 2012, Samsung surpassed Nokia, selling 93.5 million units as against Nokia’s 82.7 million units. Samsung has retained its top position since then.

Aside from Motorola, European brands such as Nokia, Siemens and Ericsson once held large sway over the global mobile phone market, and many new technologies were pioneered in Europe. By 2010, the influence of European companies had significantly decreased due to fierce competition from American and Asian companies, to where most technical innovation had shifted.[39][40] Apple and Google, both of the United States, also came to dominate mobile phone software.[39]

By mobile phone operator

The world’s largest individual mobile operator by number of subscribers is China Mobile, which has over 902 million mobile phone subscribers as of June 2018.[41] Over 50 mobile operators have over ten million subscribers each, and over 150 mobile operators had at least one million subscribers by the end of 2009.[42] In 2014, there were more than seven billion mobile phone subscribers worldwide, a number that is expected to keep growing.

Use

Mobile phone subscribers per 100 inhabitants. 2014 figure is estimated.

Mobile phones are used for a variety of purposes, such as keeping in touch with family members, for conducting business, and in order to have access to a telephone in the event of an emergency. Some people carry more than one mobile phone for different purposes, such as for business and personal use. Multiple SIM cards may be used to take advantage of the benefits of different calling plans. For example, a particular plan might provide for cheaper local calls, long-distance calls, international calls, or roaming.

The mobile phone has been used in a variety of diverse contexts in society. For example:

- A study by Motorola found that one in ten mobile phone subscribers have a second phone that is often kept secret from other family members. These phones may be used to engage in such activities as extramarital affairs or clandestine business dealings.[43]

- Some organizations assist victims of domestic violence by providing mobile phones for use in emergencies. These are often refurbished phones.[44]

- The advent of widespread text-messaging has resulted in the cell phone novel, the first literary genre to emerge from the cellular age, via text messaging to a website that collects the novels as a whole.[45]

- Mobile telephony also facilitates activism and citizen journalism.

- The United Nations reported that mobile phones have spread faster than any other form of technology and can improve the livelihood of the poorest people in developing countries, by providing access to information in places where landlines or the Internet are not available, especially in the least developed countries. Use of mobile phones also spawns a wealth of micro-enterprises, by providing such work as selling airtime on the streets and repairing or refurbishing handsets.[46]

- In Mali and other African countries, people used to travel from village to village to let friends and relatives know about weddings, births, and other events. This can now be avoided in areas with mobile phone coverage, which are usually more extensive than areas with just land-line penetration.

- The TV industry has recently started using mobile phones to drive live TV viewing through mobile apps, advertising, social TV, and mobile TV.[47] It is estimated that 86% of Americans use their mobile phone while watching TV.

- In some parts of the world, mobile phone sharing is common. Cell phone sharing is prevalent in urban India, as families and groups of friends often share one or more mobile phones among their members. There are obvious economic benefits, but often familial customs and traditional gender roles play a part.[48] It is common for a village to have access to only one mobile phone, perhaps owned by a teacher or missionary, which is available to all members of the village for necessary calls.[49]

Content distribution

In 1998, one of the first examples of distributing and selling media content through the mobile phone was the sale of ringtones by Radiolinja in Finland. Soon afterwards, other media content appeared, such as news, video games, jokes, horoscopes, TV content and advertising. Most early content for mobile phones tended to be copies of legacy media, such as banner advertisements or TV news highlight video clips. Recently, unique content for mobile phones has been emerging, from ringtones and ringback tones to mobisodes, video content that has been produced exclusively for mobile phones.[citation needed]

Mobile banking and payment

In many countries, mobile phones are used to provide mobile banking services, which may include the ability to transfer cash payments by secure SMS text message. Kenya’s M-PESA mobile banking service, for example, allows customers of the mobile phone operator Safaricom to hold cash balances which are recorded on their SIM cards. Cash can be deposited or withdrawn from M-PESA accounts at Safaricom retail outlets located throughout the country and can be transferred electronically from person to person and used to pay bills to companies.

Branchless banking has also been successful in South Africa and the Philippines. A pilot project in Bali was launched in 2011 by the International Finance Corporation and an Indonesian bank, Bank Mandiri.[50]