Как изменились обложки известнейших журналов начиная с самой первой до сегодняшних дней

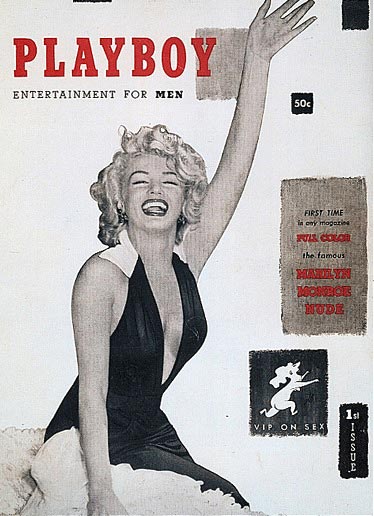

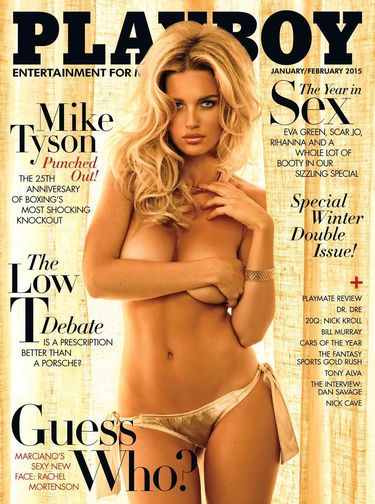

Журналы — единственная вещь, которая открывала людям дверь в мир интересной развлекательной информации до появления интернета. Многие из них уже давно прикрыли лавочку, но мастодонтам журнального дела всё нипочем, хотя и они сейчас переживают не лучшие времена. Вы знали, что самую первую обложку журнала «Playboy» украсила собой Мэрилин Монро? Скорее всего нет, потому как откуда вы могли это знать, если вы в глаза никогда не видели первые обложки знаменитых журналов. Можете не переживать по этому поводу, 20 самых известных из них ждут вас далее.

Playboy, в 1953 и в 2015

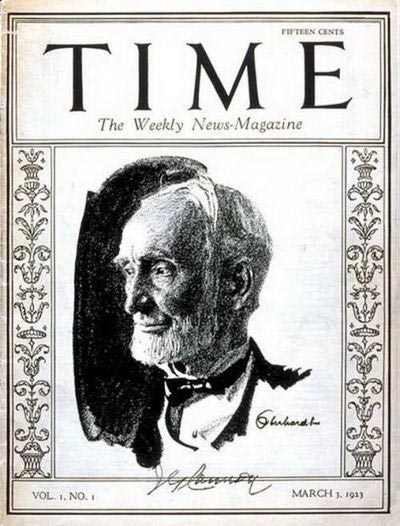

Time, в 1923 и в 2015

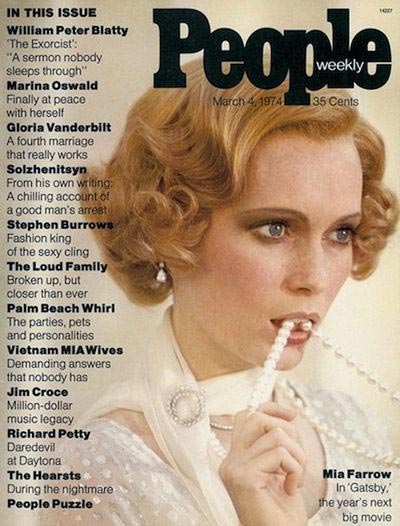

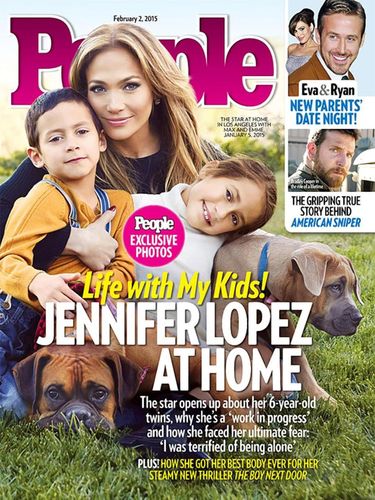

People, в 1974 и в 2015

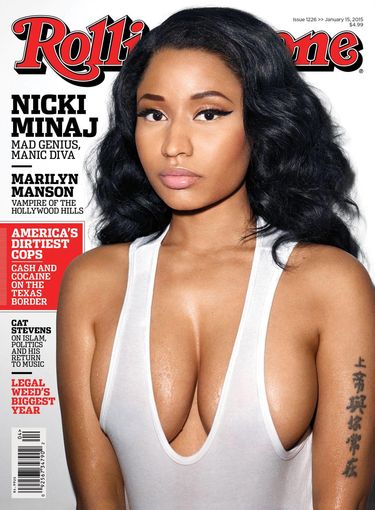

Rolling Stone, в 1967 и в 2015

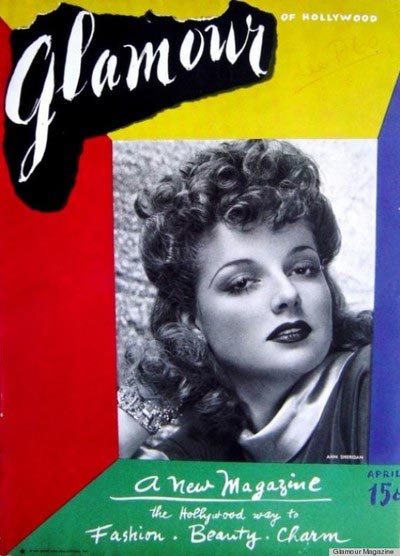

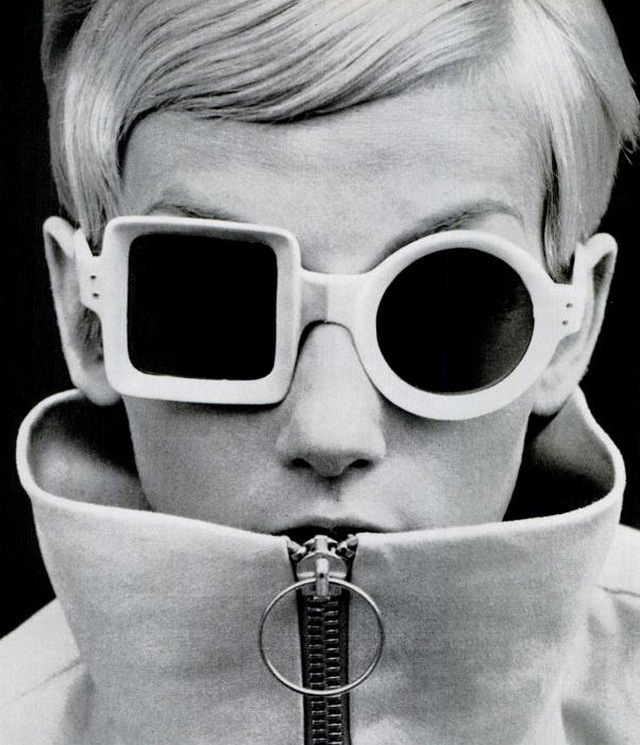

Glamour, в 1939 и в 2015

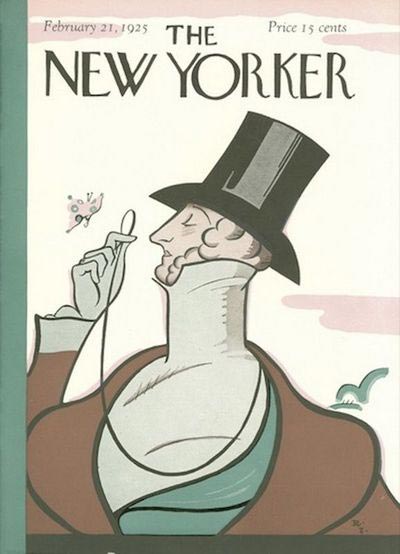

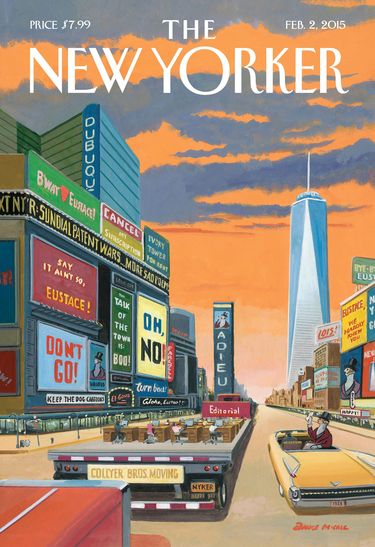

New Yorker, в 1925 и в 2015

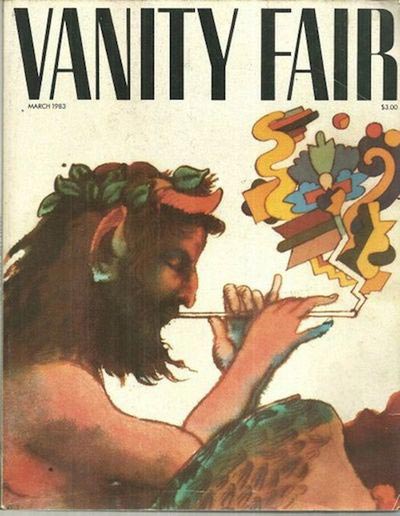

Vanity Fair, в 1983 и в 2015

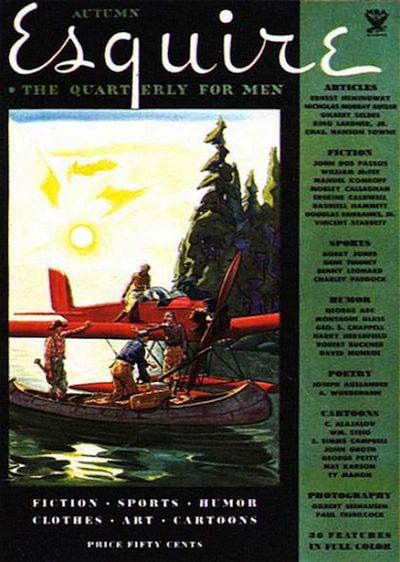

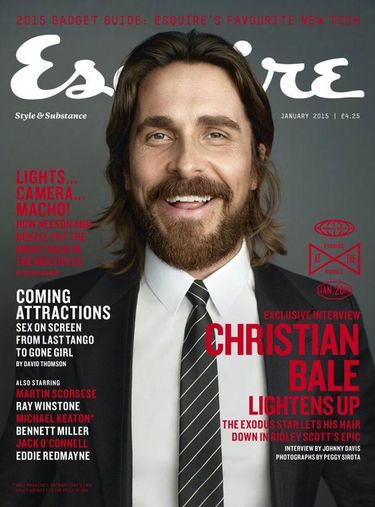

Esquire, в 1933 и в 2015

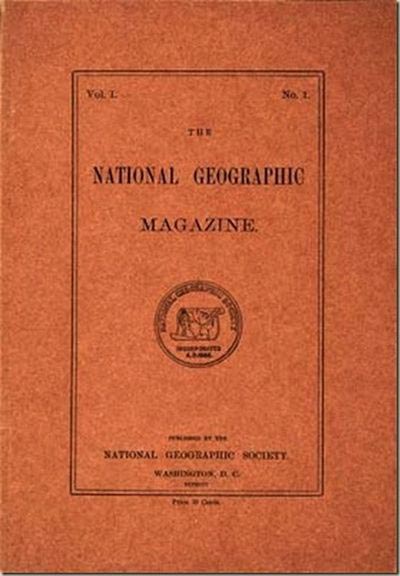

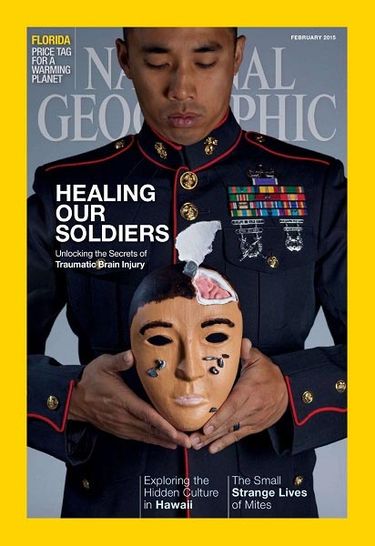

National Geographic, в 1888 и в 2015

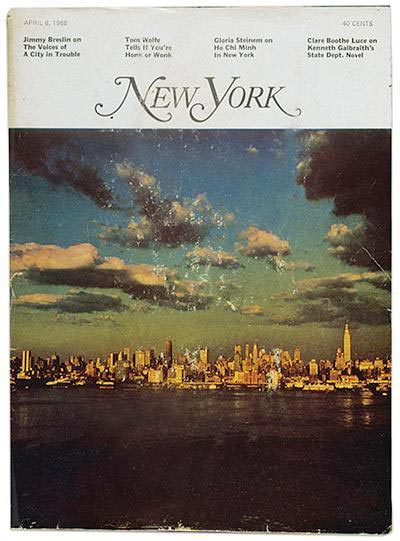

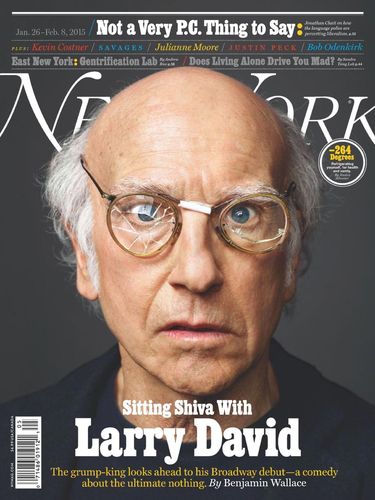

New York Magazine, в 1968 и в 2015

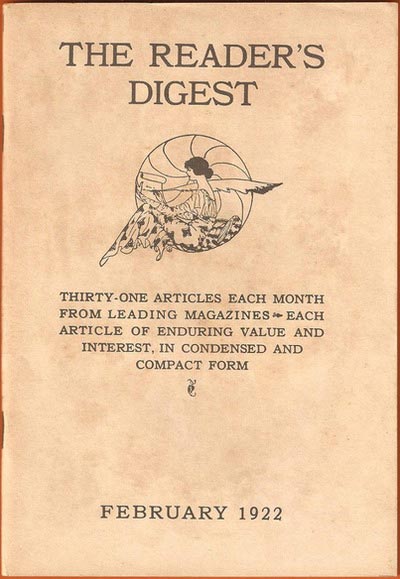

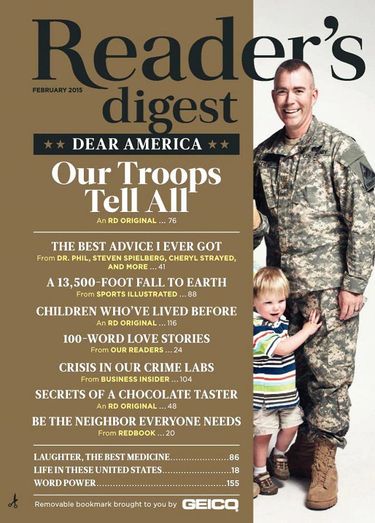

Reader’s Digest, в 1922 и в 2015

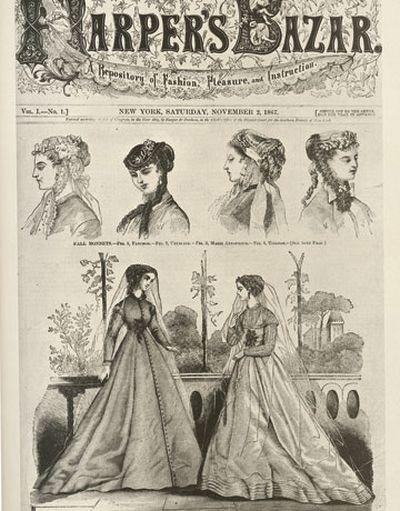

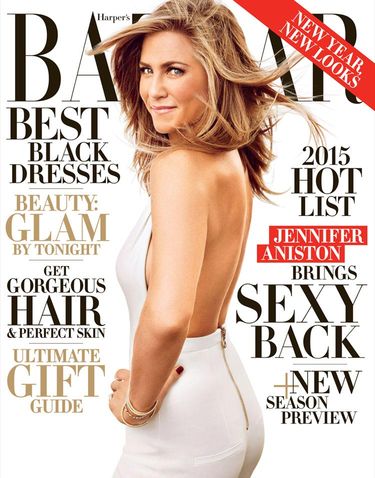

Harper’s Bazaar, в 1867 и в 2015

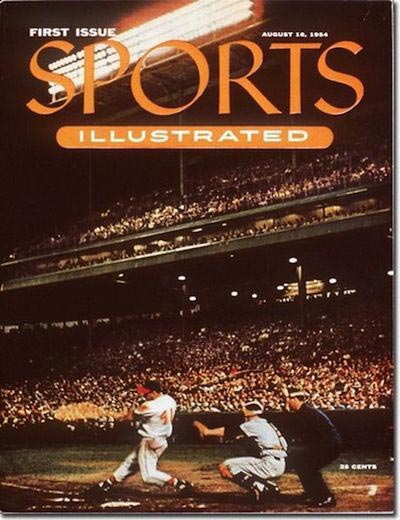

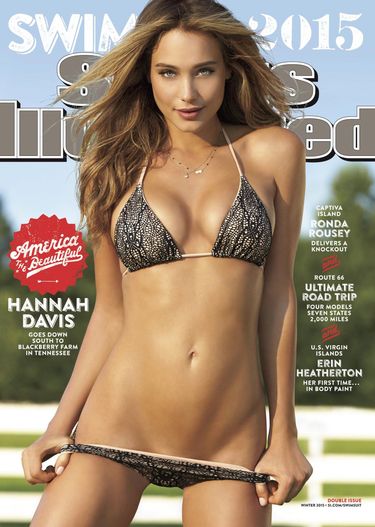

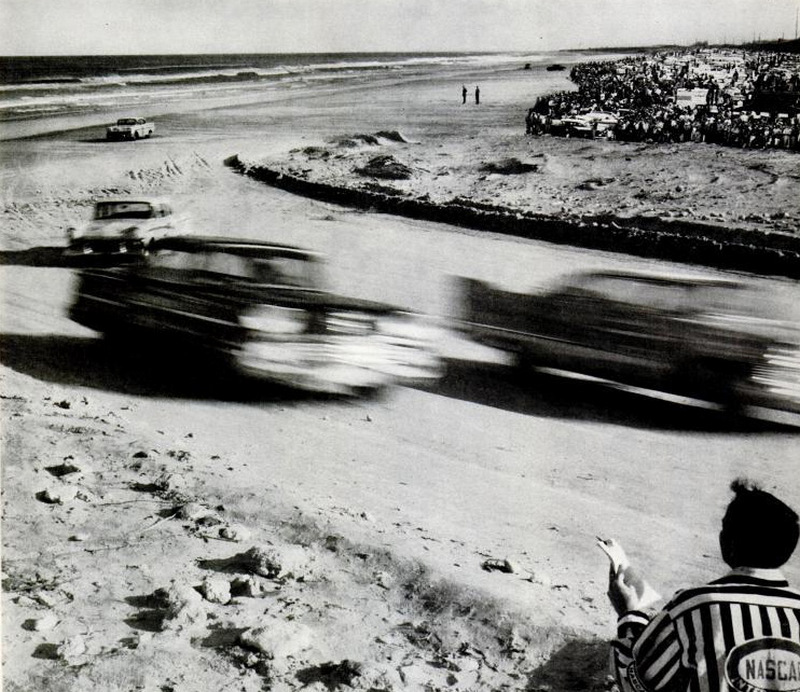

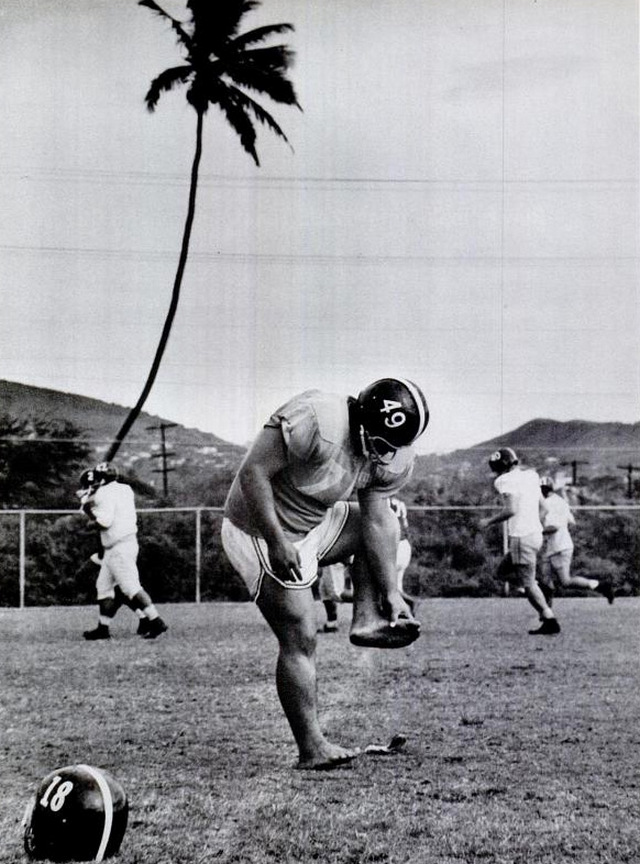

Sports Illustrated, в 1954 и в 2015

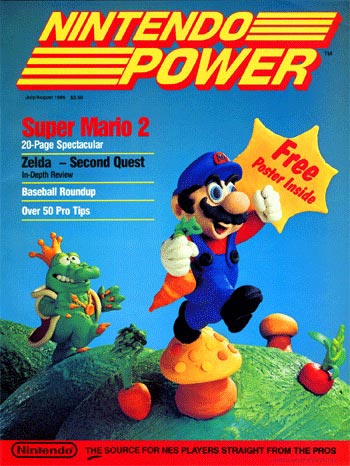

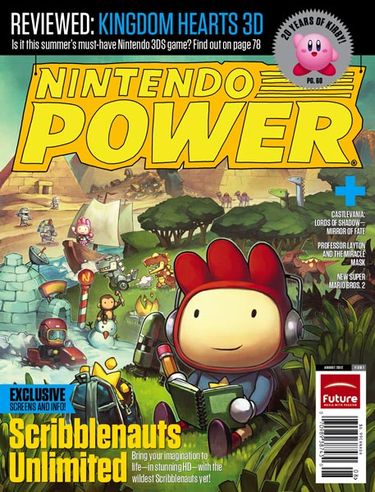

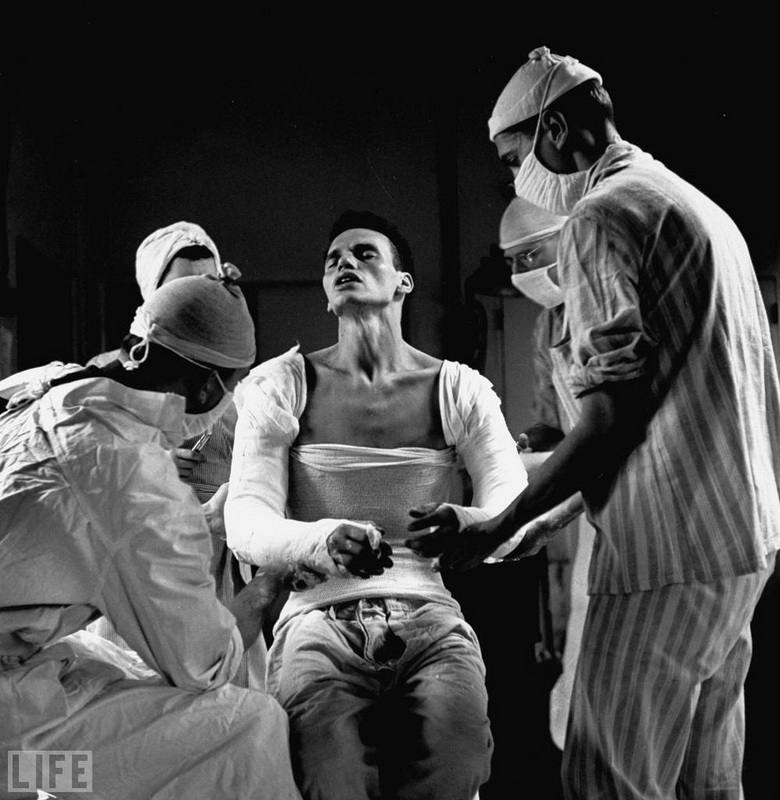

Nintendo Power, в 1988 и в 2012

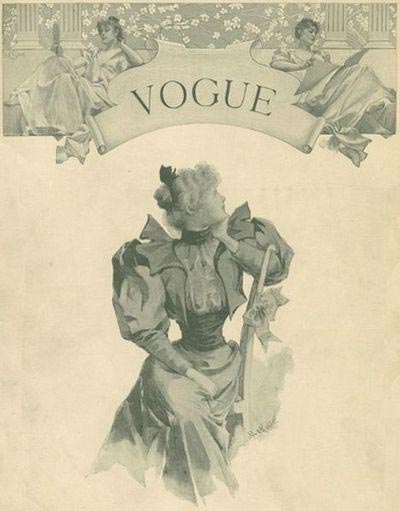

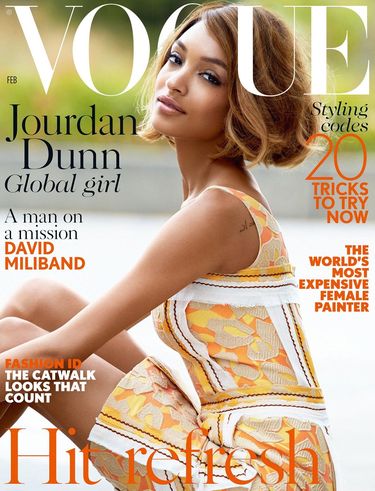

Vogue, в 1893 и в 2015

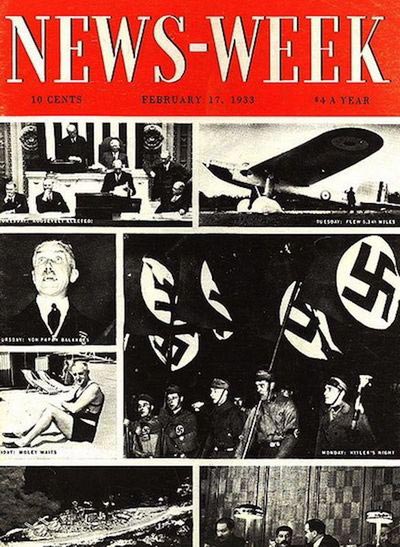

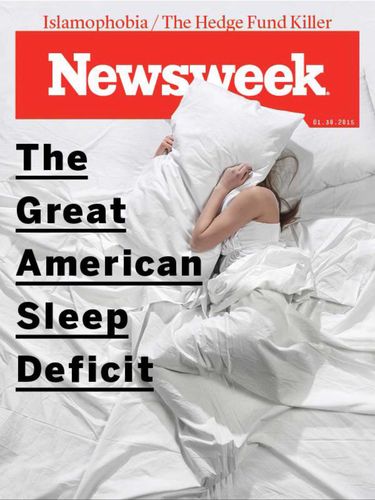

Newsweek, в 1933 и в 2015

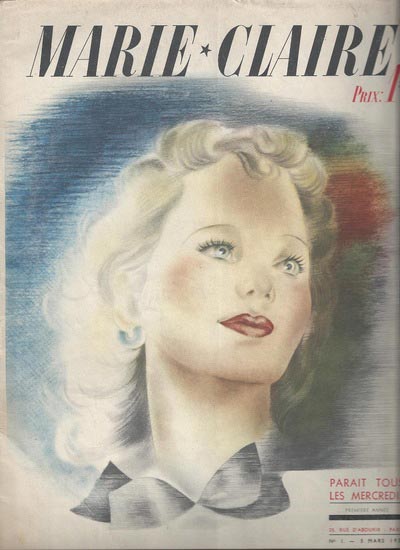

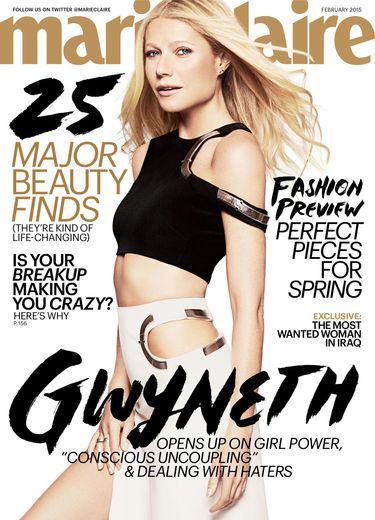

Marie Claire, в 1937 и в 2015

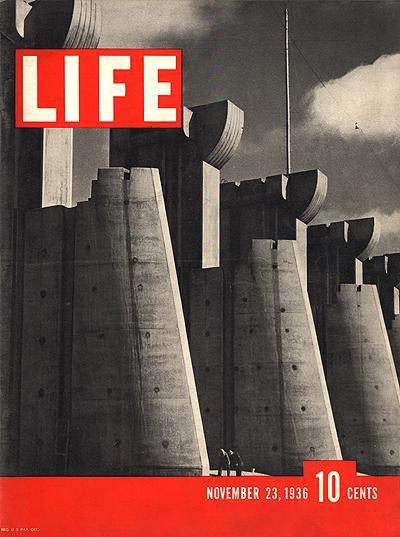

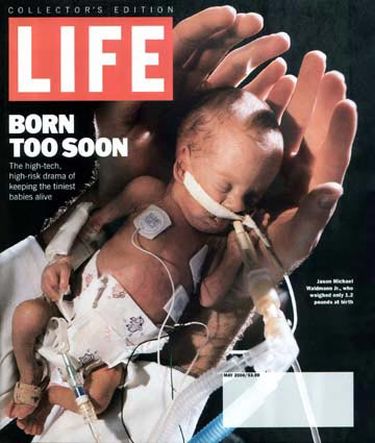

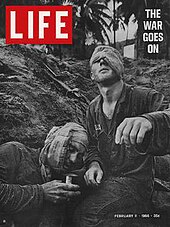

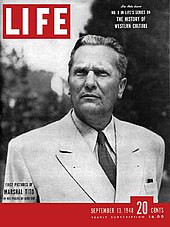

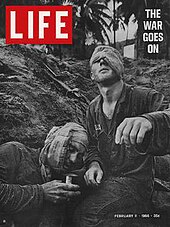

Life, 1936 и обложка последнего номера, вышедшая в мае 2000 года

Американский журналист Джордж Стори (George Story) родился чуть ли не в один день с журналом «Life» в 1936 году. В первом номере «Life» появилась фотография новорожденного Джорджа с подзаголовком «Жизнь начинается». В дальнейшем судьба Стори периодически освещалась на страницах журнала — две его женитьбы, отцовство, уход на пенсию. 64-летний Джордж появился и в последнем выпуске, в мае 2000 года, на этот раз под заголовком «Жизнь заканчивается» (имелось в виду закрытие журнала). Через несколько дней Джордж Стори скончался от инфаркта.

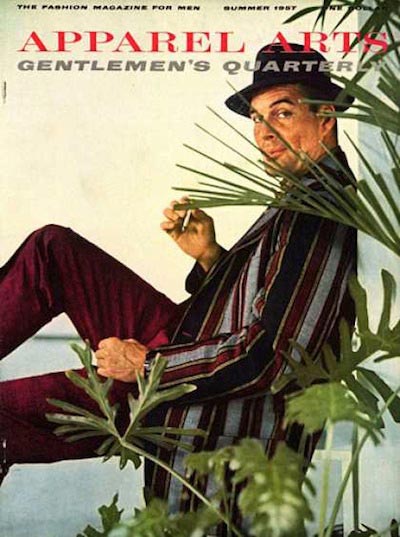

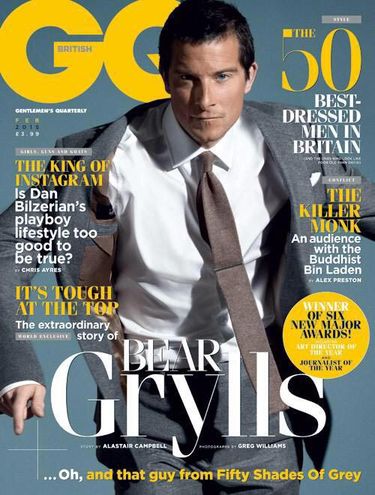

GQ (изначально журнал назывался Apparel Arts Gentlemen’s Quarterly), в 1957 и в 2015

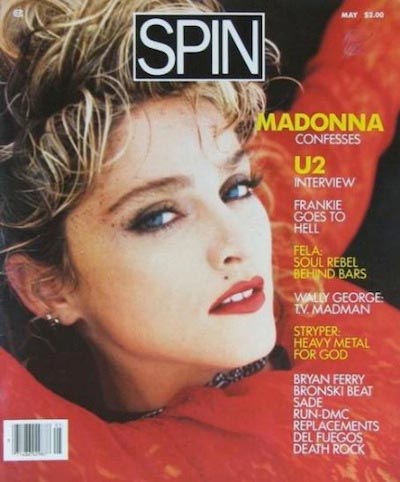

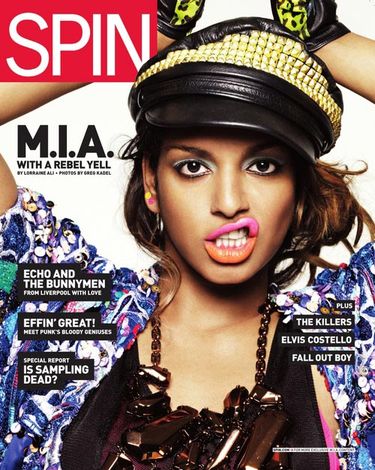

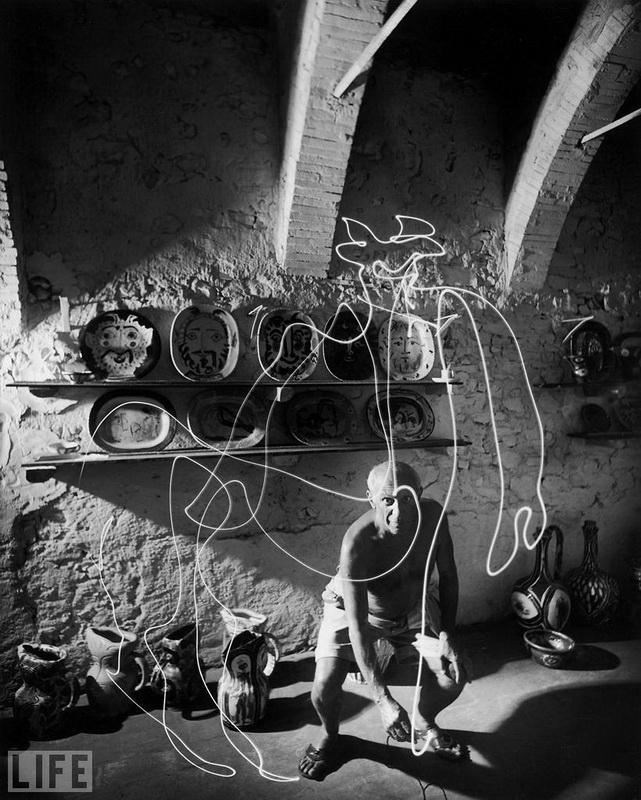

Spin, в 1985 и в 2014

Pg… 1

Cover: Born Too soon: The high-risk drama of keeping the tiniest babies alive: Jason Michael Waldmann Jr. who weighed only 1.2 pounds at birth

Pg… 6

Publisher»s Note: Last monthly issue of LIFE magazine

Pg… 12

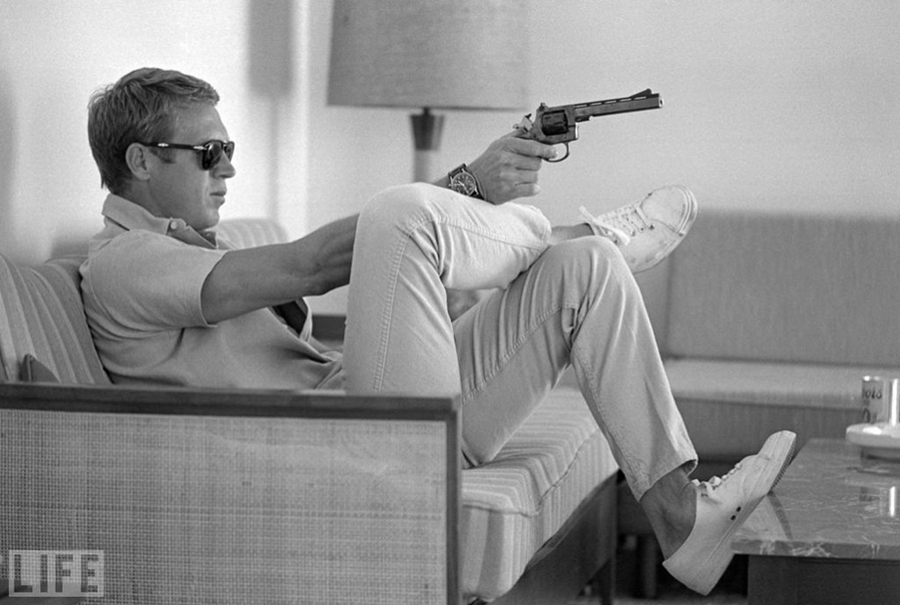

The Big Picture: In Texas, a tornado leaves a house in tatters; in Illinois, a basset hound nurtures an unlikely family; in Uganda, a cult leaves only horror behind

Pg… 22

Life Around the World: A family man in Jakarta proves that hope is stronger than any hardship or handicap

Pg… 31

Bob Greene: LIFE columnist bids farewell to his first love

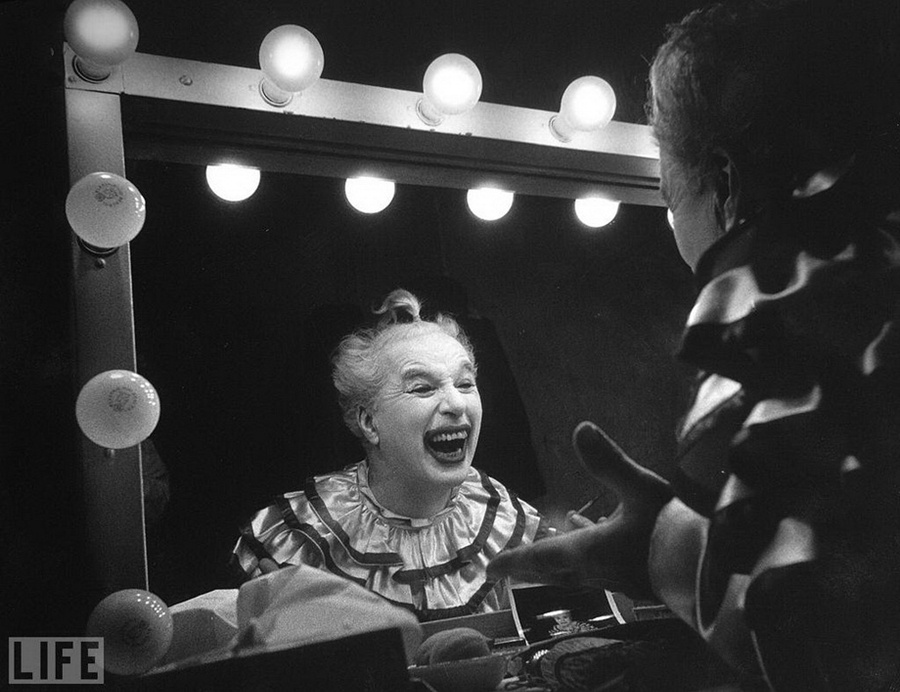

Pg… 34

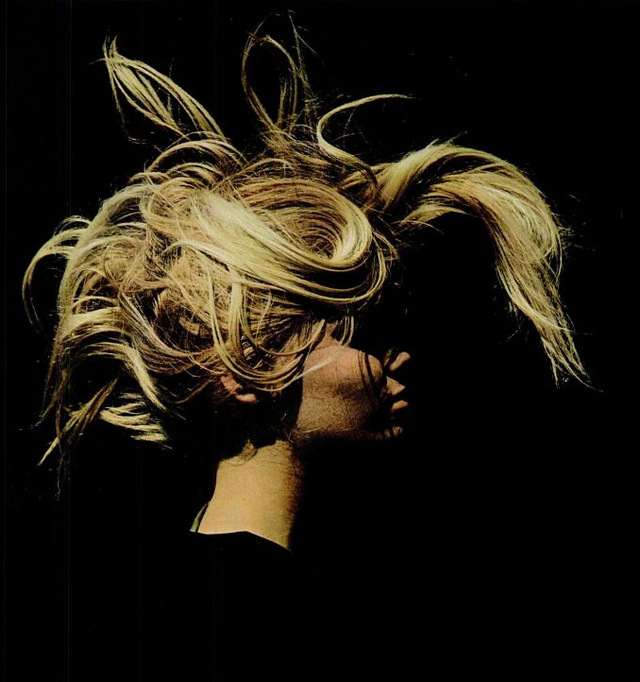

Then and Now: What ever happened to some of LIFE»s favorite story subjects

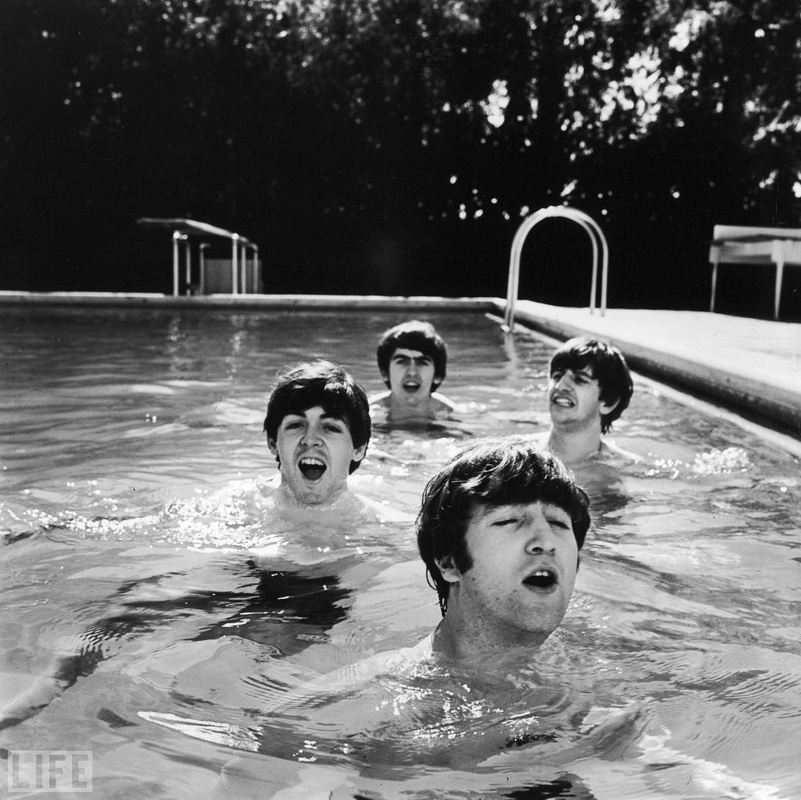

Pg… 44

Coming Back to Life: Twenty years later, the natural beauty of Mount St. Helens rises from the ashes. By Charles Hirshberg. Photography by Gary Braasch

Pg… 48

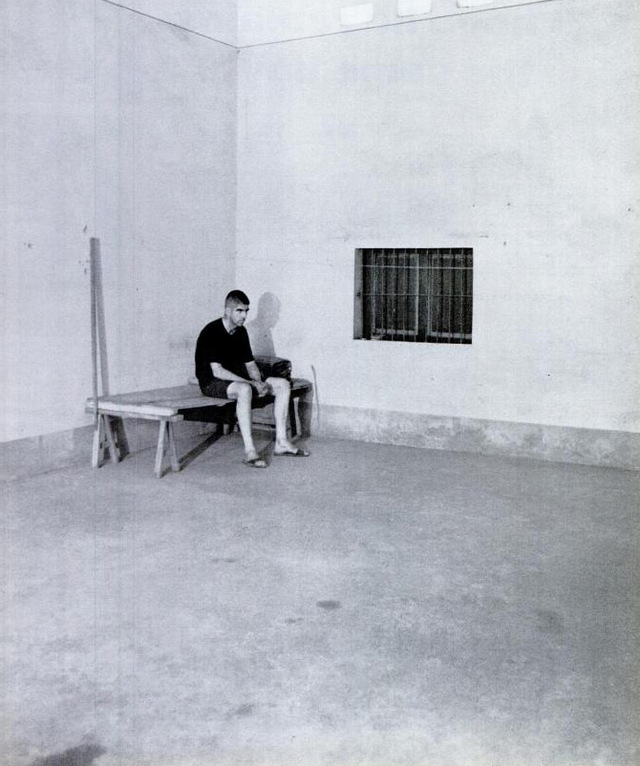

Saving Jason: Only 1.2 pounds at birth, Jason Michael Waldmann Jr. was born too soon. But new technology, and old-fashioned care, are keeping tinier and tinier babies alive. By Lise Funderburg. Photography by Co Rentmeester

Pg… 66

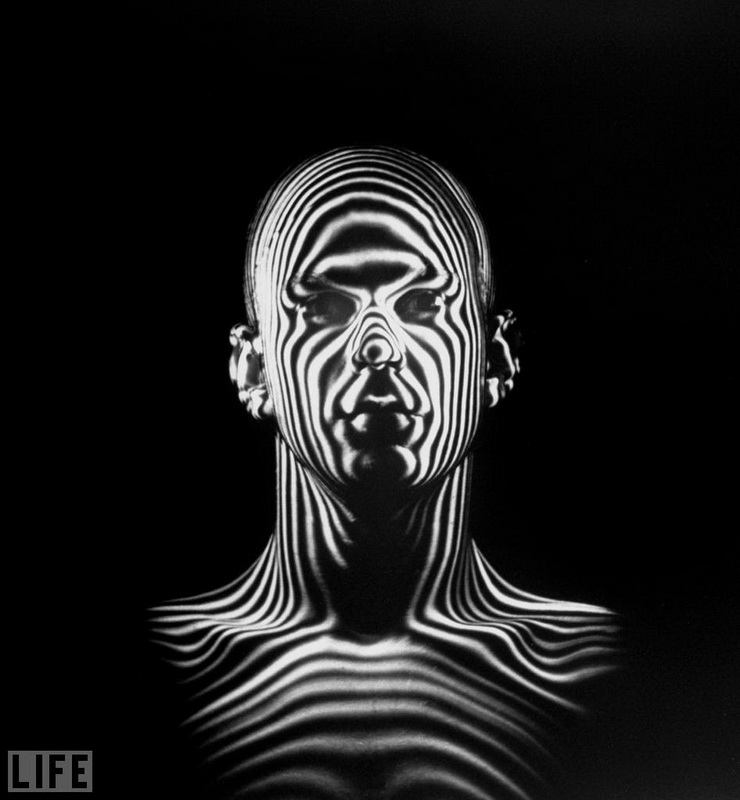

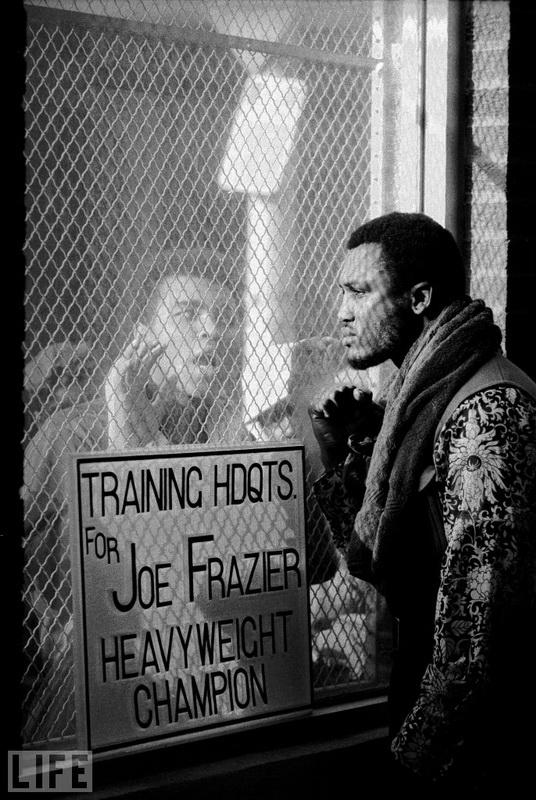

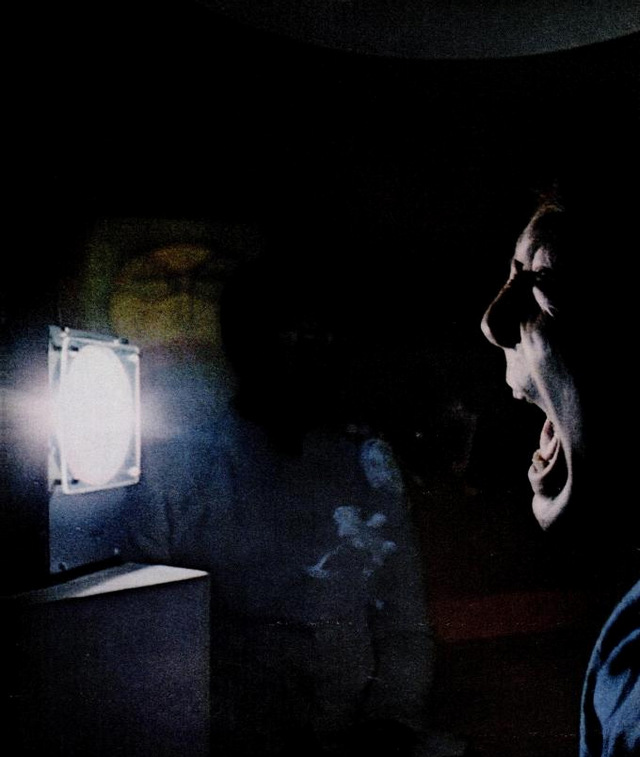

Making Faces: A portrait photographer asks his subjects: «What do you see?» Photography by Steve Pyke

Pg… 76

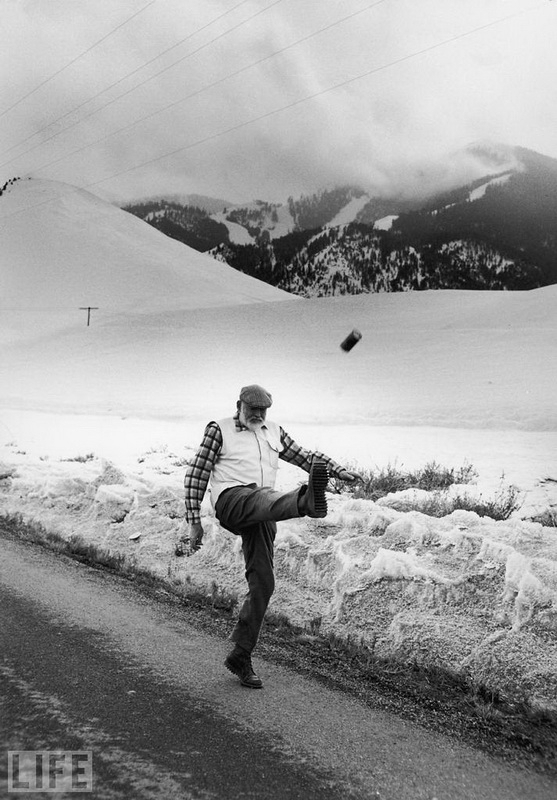

The Vanishing Wild: For his new book, a nature photographer set out to document the world»s animals before it»s too late. Photography by Art Wolfe

Pg… 106

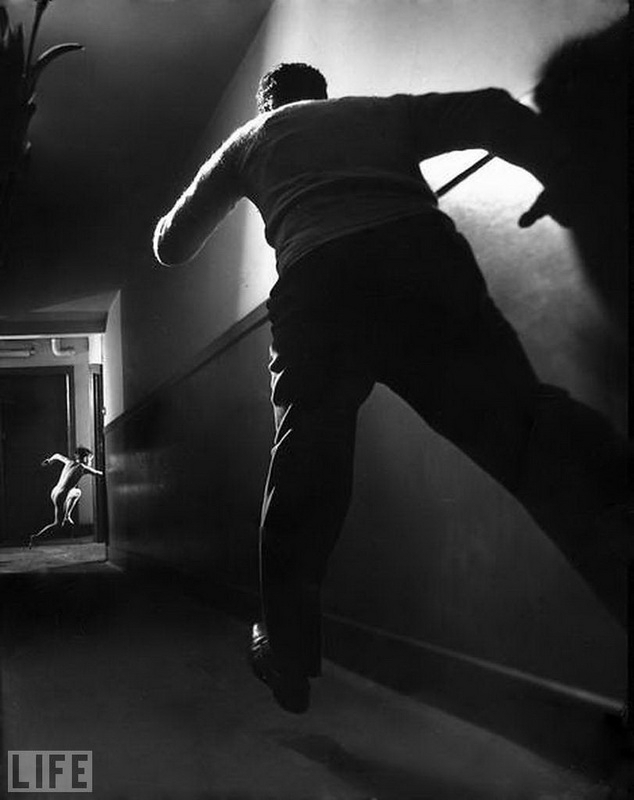

Just One More: The people who brought LIFE to life

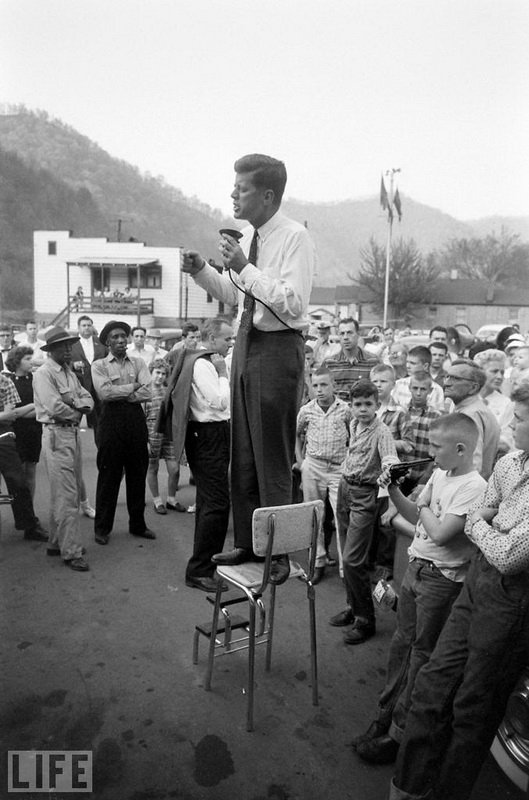

С 1936 по 1972 года новостной журнал «LIFE» выходил еженедельно. С 1978 по 2000 года выпуски стали появляться раз в месяц. В этой подборке можно увидеть знаменитые фотографии, публиковавшиеся на обложке «LIFE».

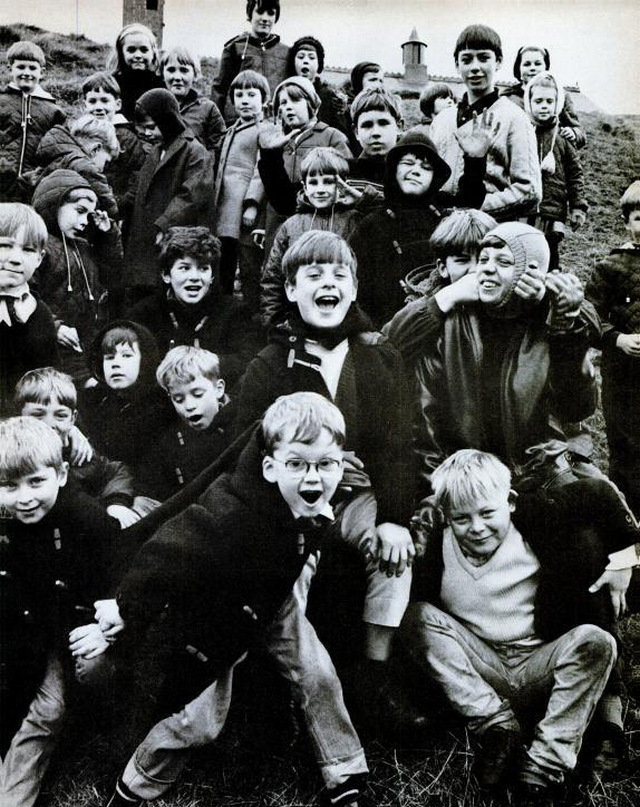

1. Представление театра кукол. (The Puppet Show). Photo by Alfred Eisenstaedt, 1963. Эмоции детей во время кукольного представления. На сцене Святой Георгий убивает змея.

2. Goin’ Home. Photo by Ed Clark, 1945. На похоронах президента Рузвельта 12 апреля 1945 года звучала песня «Goin’ Home» в исполнении старшины Грэма Джексона.

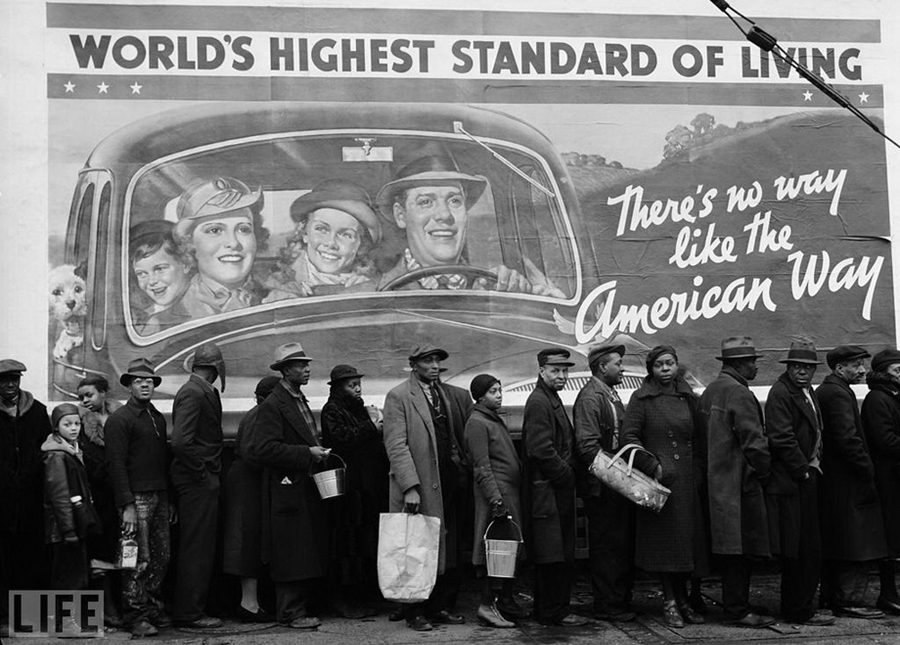

3. Образ жизни граждан Америки. (The American Way). Photo by Margaret Bourke-White, 1937. Надпись на плакате возле пункта Красного креста гласит: «Нет такого другого образа жизни, как американский». На фото: люди на фоне плаката в очереди за едой у пункта Красного креста во время Великой депрессии.

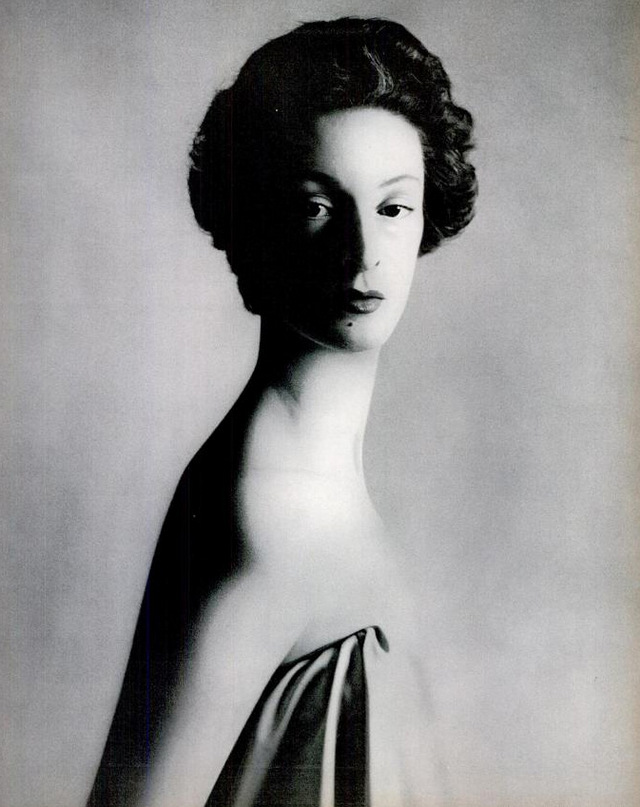

4. Марлен Дитрих (Marlene Dietrich). Photo by Milton Greene, 1952.

5. Длинный день (The Longest Day). Photo by Robert Capa, 1944. На фотографии: момент высадки американских военных на Омаха-бич в Нормандии 6 июня 1944 года. Это событие было отражено в фильме Стивена Спилберга «Спасти рядового Райана».

6. Глаза ненависти (Eyes of Hate). Photo by Alfred Eisenstaedt, 1933. Геббелс (на кресле) не скрывает своих эмоций, узнав, что его переводчик еврей.

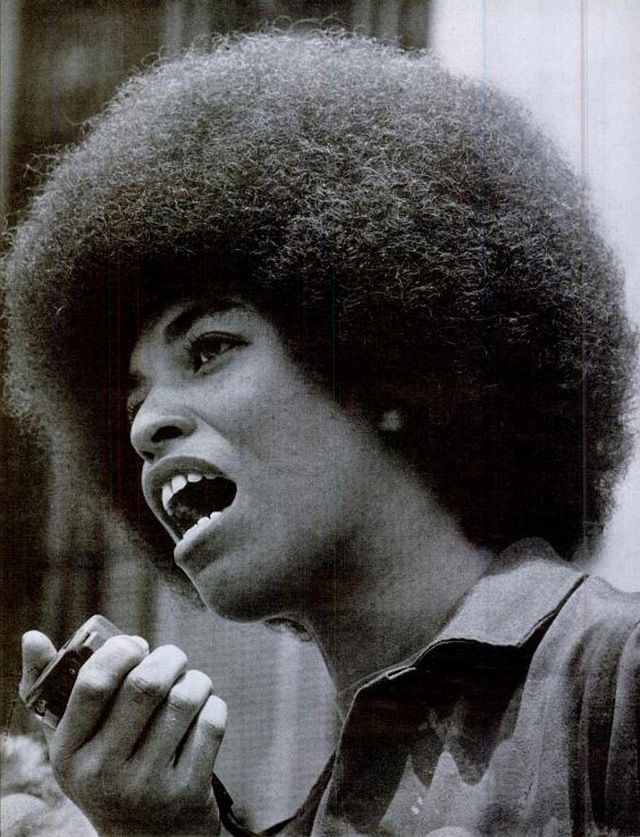

7. Meeting peace With fire hoses. Photo by Charles Moore, 1963. Для разгона мирного митинга против сегрегации в Бирмингеме (штат Алабама) использовались пожарные брандспойты.

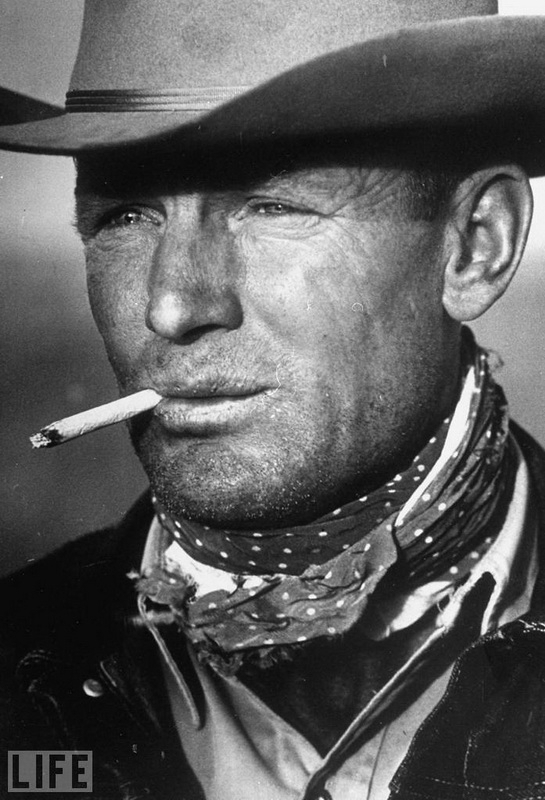

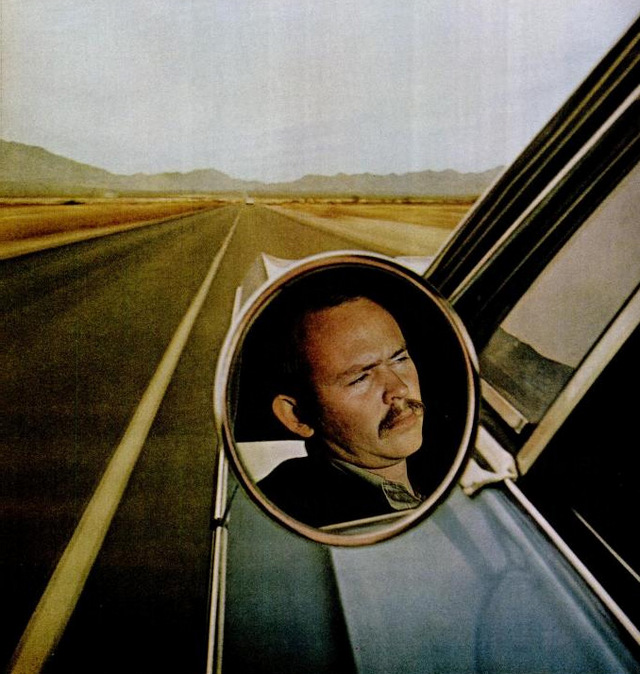

8. «The Marlboro Man». Photo by Leonard McCombe, 1949. Образ 39-летнего техасского ковбоя Clarence Hailey был использован неоднократно для рекламы сигарет.

9. Peek-A-Boo. Photo by Ed Clark, 1958. Джон Кеннеди со своей дочерью Кэролайн.

10. Песок Иводзимы (Sand of Iwo Jima). Photo by Photo by W. Eugene Smith, 1945. Битва за Иводзиму весной 1945 года с участием американских морских пехотинцев.

11. Освобождение узников Бухенвальда (Liberation of Buchenwald). Photo by Margaret Bourke-White, 1945.

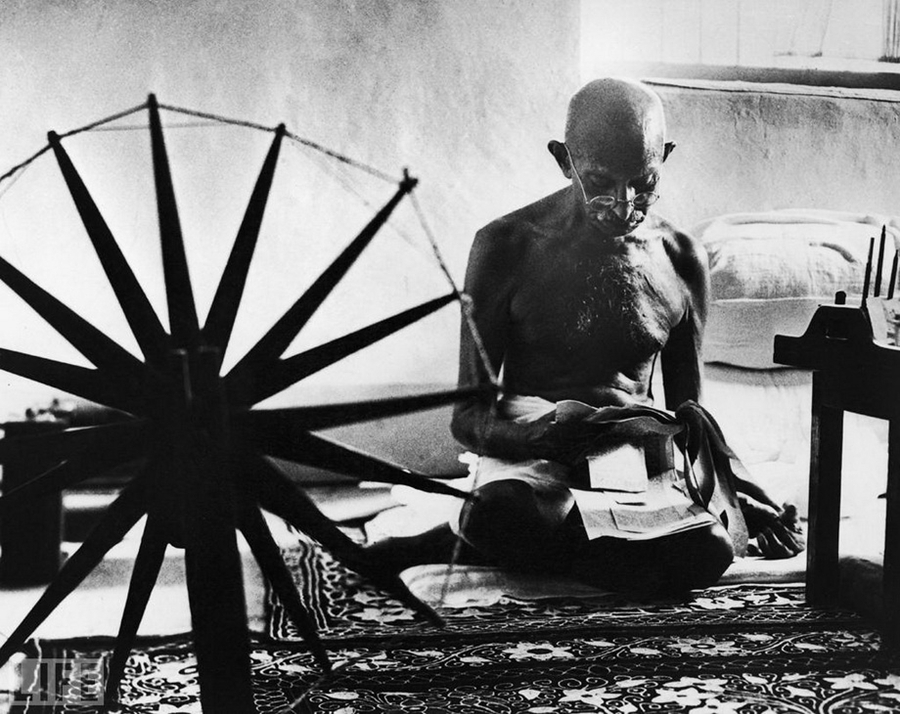

12. Великая душа (The Great Soul). Photo by Margaret Bourke-White, 1946. Махатма Ганди рядом с символом ненасильственного движения за независимость Индии от Великобритании — прялкой.

13. A Child Is Born. Photo by Lennart Nilsson, 1965. Снимок ребенка в утробе матери стал первым в мире.

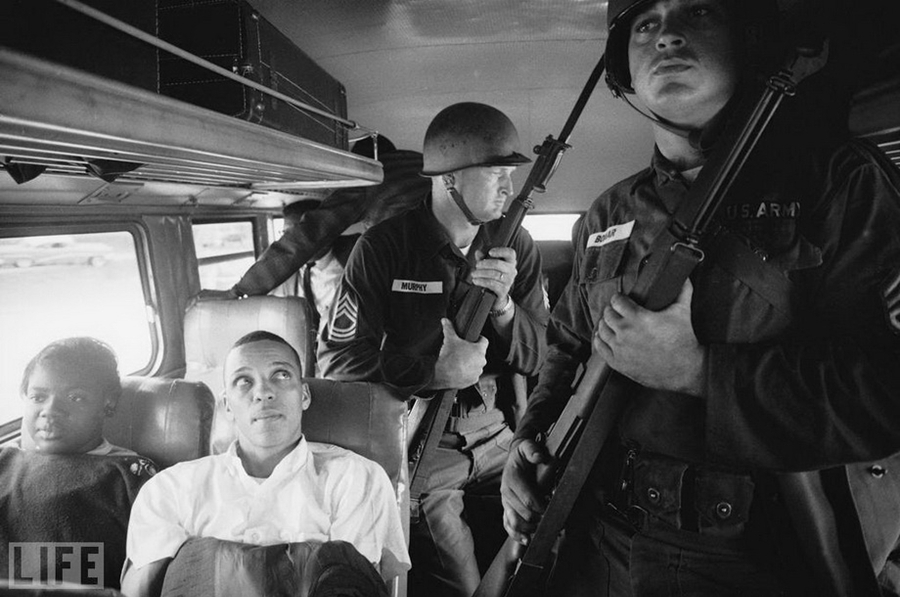

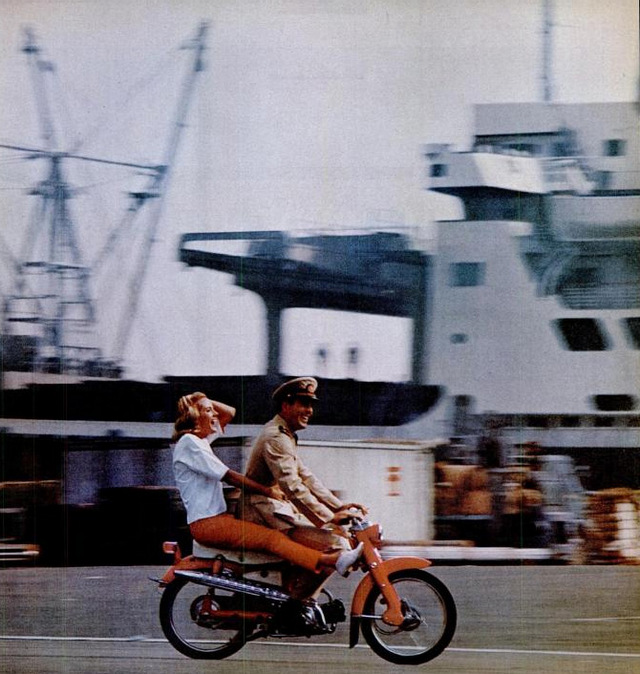

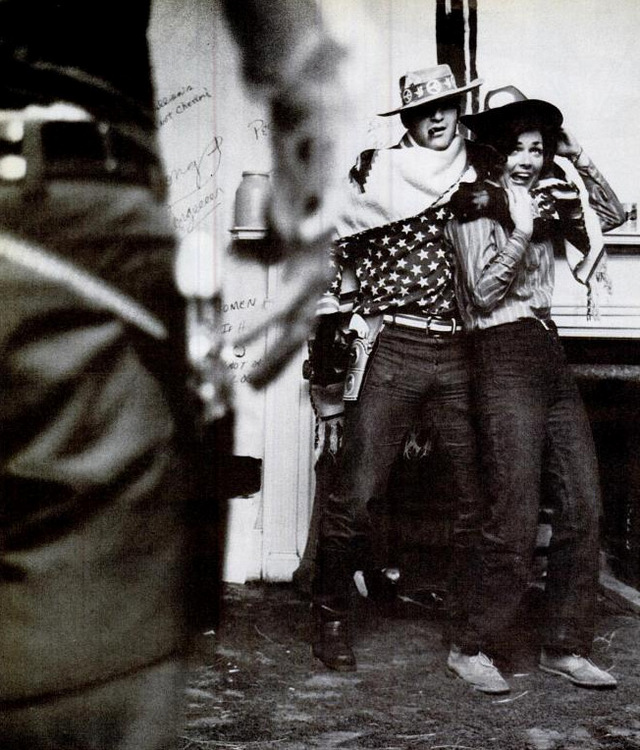

14. Всадники свободы (Freedom Riders). Photo by Paul Schutzer, 1961. «Всадниками свободы» называли совместные автобусные поездки черных и белых активистов, которые протестовали против нарушения прав чернокожего населения в южных штатах США. В 1961 году активисты арендовали автобусы и колесили по южным штатам, неоднократно подвергаясь нападениям со стороны белых южан и арестам. Во время поездки из Монтгомери (штат Алабама) в Джексоне (штат Миссисипи) для защиты «всадников» были выделены солдаты Национальной гвардии.

15. Агония (Agony): Photo by Ralph Morse, 1944. Армейский медик Джордж Лотт получил тяжелые ранения обоих рук.

16. Море шляп (Sea of Hats). Photo by Margaret Bourke-White, 1930. Толпа в шляпах на улицах Нью-Йорка.

17. Reaching Out: Photo by Larry Burrows, 1966. Раненные морской пехотинец во время военных действий во Вьетнаме.

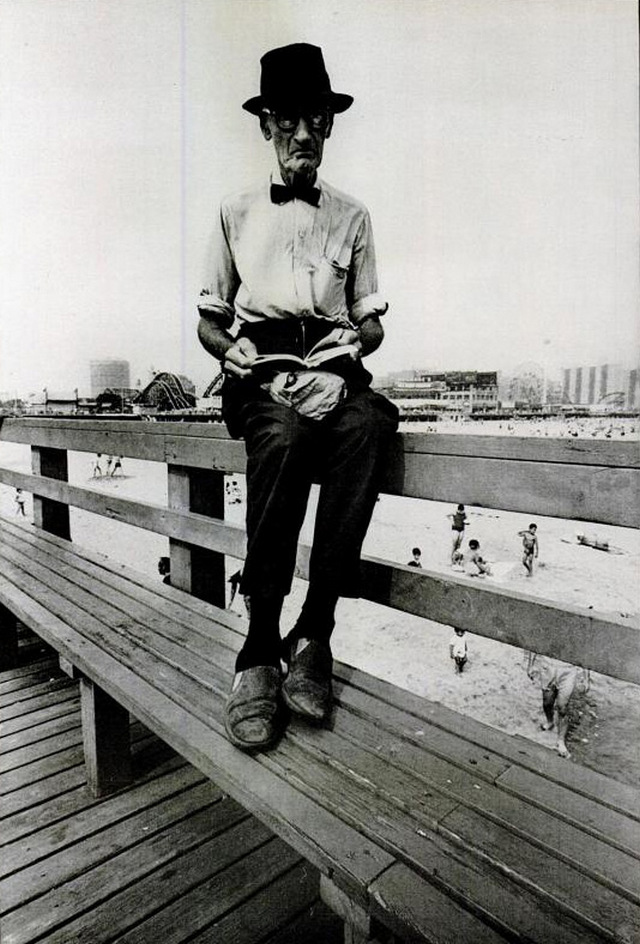

18. Alexander Solzhenitsyn Breathes Free. Photo by Harry Benson. Александр Солженицын в Вермонте.

19. Королевские прыжки (Jumping Royals). Photo by Philippe Halsman, 1959. Герцог и герцогиня Виндзор

20. В центре внимания (Center of Attention). Photo by Leonard McCombe, 1956.

21. Лицо смерти (Face of Death). Photo by Ralph Morse, 1943. Танк с головой японского солдата.

22. Пикассо и кентавр (Picasso and Centaur). Photo by Gjon Mili, 1949. Рисунок в воздухе.

23. Уинстон Черчилль (Winston Churchill). Photo by Yousuf Karsh, 1941. Уинстон Черчилль занимал пост премьер-министра Великобритании в 1940—1945 и 1951—1955 годах. Политик, военный, журналист, писатель. Стал лауреатом Нобелевской премии по литературе.

24. Леопард-убийца (A Leopard’s Kill). Photo by John Dominis, 1966. Леопард с жертвой.

25. Крысолов из Энн-Арбор (Pied Piper of Ann Arbor). Photo by Alfred Eisenstaedt, 1950. Во главе колонны детей барабанщик из Мичиганского университета.

26. Человек реактивного века (Jet Age Man). Photo by Ralph Morse, 1954. Пилот реактивного самолета.

27. 3D Movie Audience. Photo by J.R. Eyerman, 1952. Люди смотрят первый полнометражный стерео-фильм Bwana Devil.

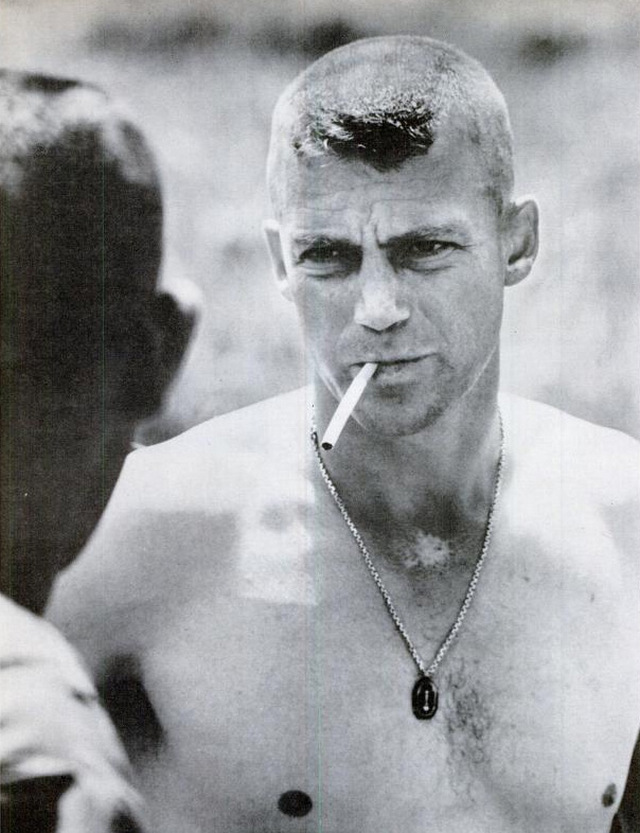

28. Steve McQueen. Photo by John Dominis, 1963. Актер Стив Маккуин, снявшийся в фильме «Великолепная семерка».

29. Сельский врач (Country Doctor). Photo by W. Eugene Smith, 1948. Ernest Ceriani был единственным врачом на 1200 квадратных миль региона. На фото: доктор после неудачной операции кесарева сечения, в ходе которой из-за осложнений погибли мать и ребенок.

30. Три американца (Three Americans). Photo by George Strock, 1943. Трупы американских солдат, погибших в бою с японцами на пляже в Новой Гвинее. Это был первый фотоснимок мертвых американских солдат в ходе Второй мировой войны.

31. Jack and Bobby: Photo by Hank Walker, 1960. Джон Кеннеди (на тот момент еще сенатор) со своим братом Робертом в гостинице во время съезда Демократической партии в Лос-Анджелесе.

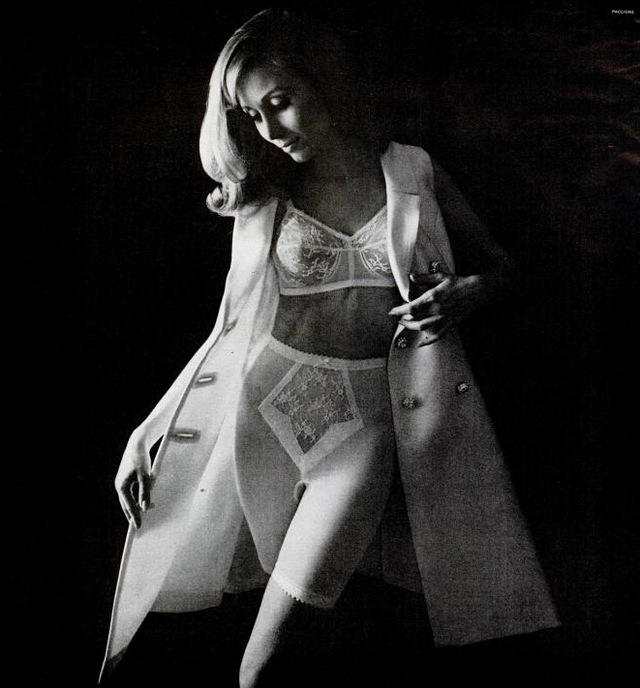

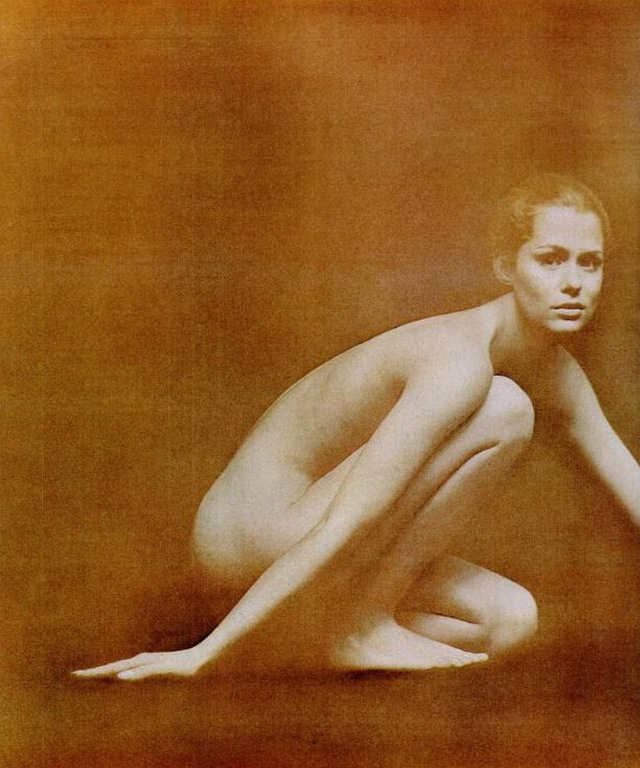

32. Sophia Loren. Photo by Alfred Eisenstaedt, 1966. Кадр из фильма «Брак по-итальянски» с Софи Лорен. Когда вышел этот номер журнала «LIFE», он получил критику со стороны читателей за столь откровенные снимки. Один читатель написал: «Слава Богу, что почтальон приходит в полдень, когда мои дети в школе».

33. Charlie Chaplin. Photo by W. Eugene Smith, 1952. Чарли Чаплин в возрасте 63 лет.

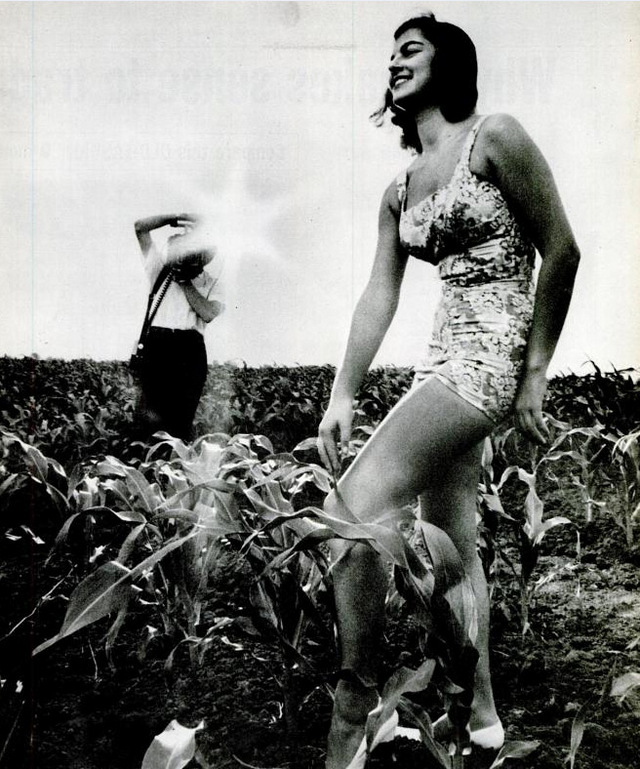

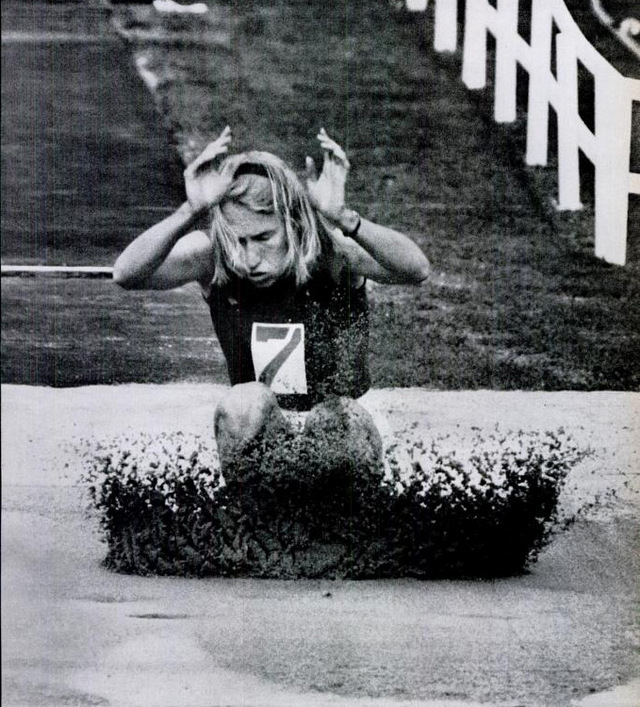

34. Gunhild Larking. Photo by George Silk, 1956. Gunhild Larking — шведская прыгунья в высоту. На фото: Gunhild на Олимпийских играх 1956 года в Мельбурне.

35. The Beatles in Miami. Photo by John Loengard, 1964. Легендарная четверка во время американских гастролей. Судя по гримасе Ринго, вода в бассейне в тот день была достаточно прохладной.

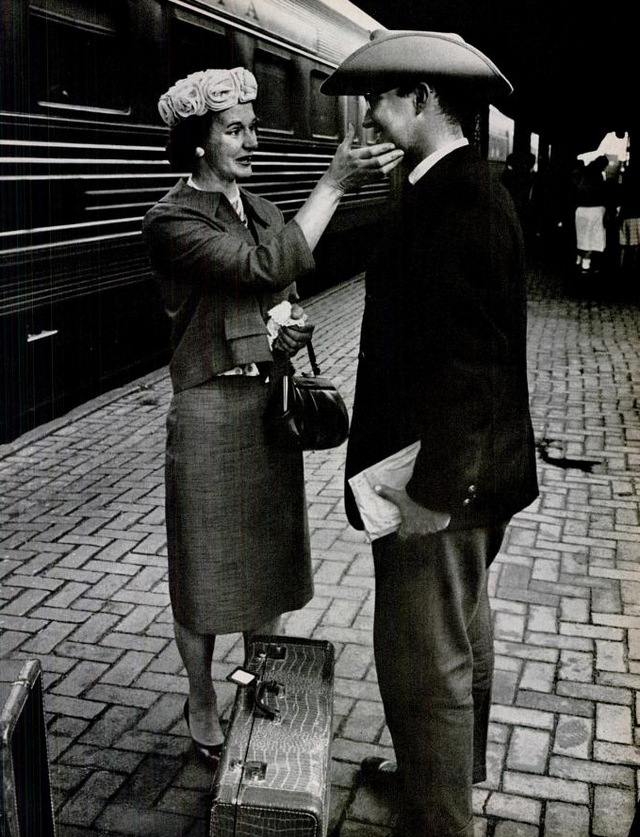

36. Перед свадьбой (Before the Wedding). Photo by Michael Rougier, 1962

37. Оставшийся в живых (Littlest Survivor). Photo by W. Eugene Smith, 1943. Оказавшиеся в осаде на острове Сайпан, сотни японцев совершили массовое самоубийство, чтобы не попасть в плен к американцам во время Второй мировой войны. На фото: чудом оставшийся в живых японский ребенок в руках американского морского пехотинца.

38. Liz and Monty: Photo by Peter Stackpole, 1950. Элизабет Тейлор и Монтгомери Клифт на съемках фильма «A Place in the Sun» студии Paramount.

39. «Dali Atomicus». Photo by Philippe Halsman, 1948. Чтобы сделать этот снимок, фотографу понадобилось шесть часов времени и 28 бросков (воды, стула и кошек). По окончанию съемок фотограф и его помощники были мокрые, грязные и истощенные.

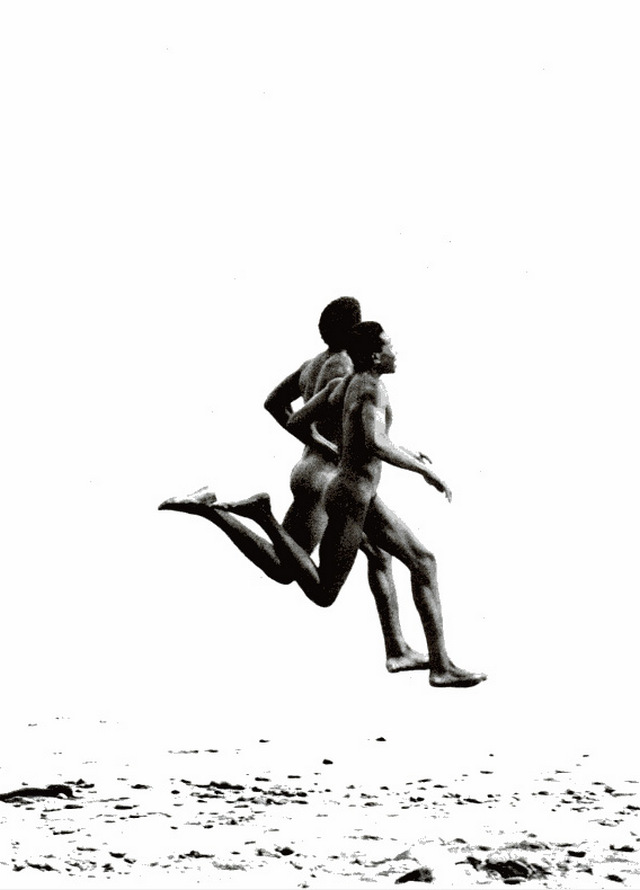

40. Both Sides Now. Photo by John Shearer, 1971. Мухаммед Али перед боем с Джо Фрейзером в марте 1971 года. Любитель дразнить оппонентов, Али, перед боем с Фрейзером подверг сомнению мужественность, интеллектуальные способности и «чернокожесть» последнего.

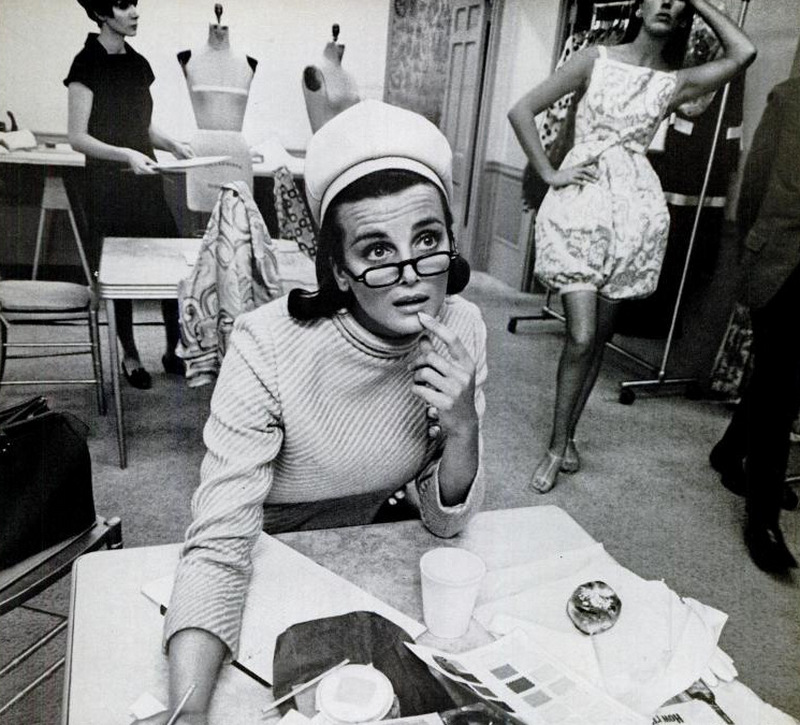

41. Ingenue Audrey: Photo by Mark Shaw, 1954. Звезда «Римских каникул» Одри Хепберн в возрасте 25 лет.

42. Лев зимой (Lion in Winter). Photo by John Bryson, 1959. Хемингуэй недалеко от своего дома в Кетчуме, штат Айдахо.

43. Расступление моря в Солт-Лейк-Сити (Parting the Sea in Salt Lake City). Photo by J.R. Eyerman, 1958. На экране автокинотеатра в столице Юты Солт-Лейк-Сити транслируется фильм «Десять заповедей»: Моисей на фоне расступающегося Красного моря.

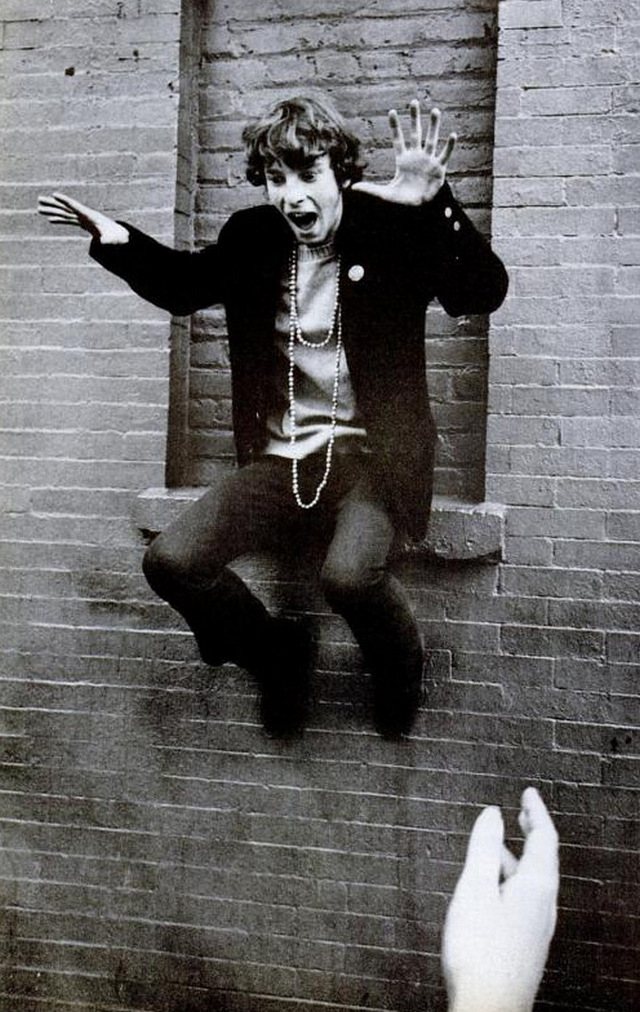

44. Побег мальчика (A Boy’s Escape). Photo by Ralph Crane, 1947. На этом постановочном снимке изображен побег мальчика из детского дома.

45. Перед Камелотом, визит в Западную Вирджинию (Before Camelot, a Visit to West Virginia). Photo by Hank Walker, 1960. Джон Кеннеди выступает во время предвыборной компании в американском городке.

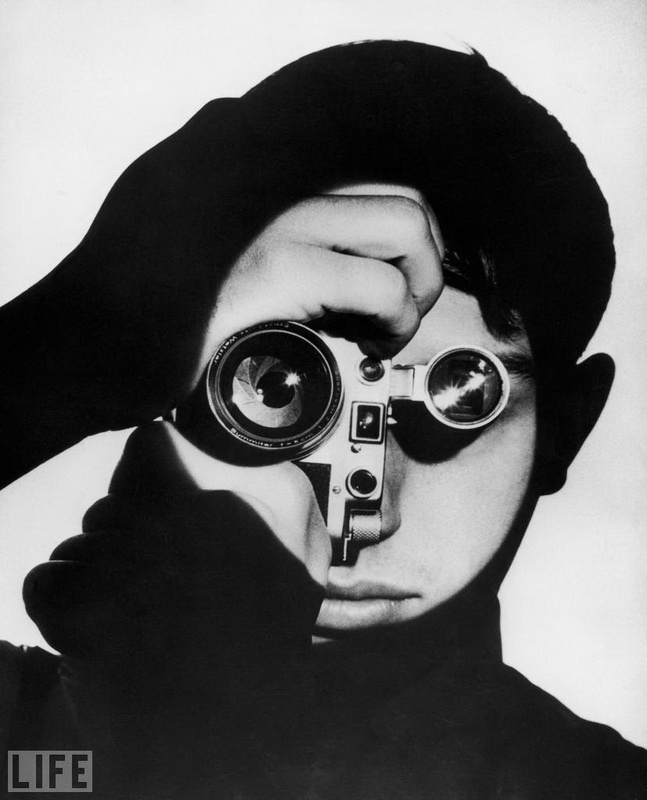

50. Dennis Stock: Photo by Andreas Feininger, 1951

Из истории американской фотожурналистики: медиамагнат Генри Люс и новый стиль фотографии журнала LIFE. Альфред Хичкок, Мэрилин Монро и Адольф Гитлер на страницах LIFE, известные фотографы и репортажи.

Американский журнал LIFE

был основан в 1883 году и имел развлекательную направленность: юмор, иллюстрации, карикатуры, комментарии.

обложка журнала LIFE

за февраль 1922 года

В 1936 году LIFE

пережил перерождение: он был куплен американским издателем Генри Люсом , который создал первую мультимедийную корпорацию (в 1923 году Люс основал еженедельный новостной журнал TIME, в 1930 году бизнесс-журнал FORTUNE, в 1951 году — журнал Sports Illustrated, также являлся создателем популярных радио и других передач).

Генри Люс изменил формат журнала — LIFE

стал фотожурналом о политике, культуре и социуме. Он выходил на 50 страницах и состоял из фотографий с небольшими комментариями-описаниями.

обложка журнала LIFE

за февраль 1963 года, подпись справа: Альфред Хичкок, фильм ужасов “Птицы”.

Фотожурналисты LIFE

работали в особенном формате: о событии, личности, информационном поводе или явлении повествовала фотография с небольшим комментарием. Соответственно, фотография должна была быть содержательной, информативной и интересной.

фотография LIFE

, фотограф Айерман , комментарий: “Чарльтон Хестон в роли Моисея в фильме “Десять заповедей”, Автокинотеатр, Юта”, 1958 год.

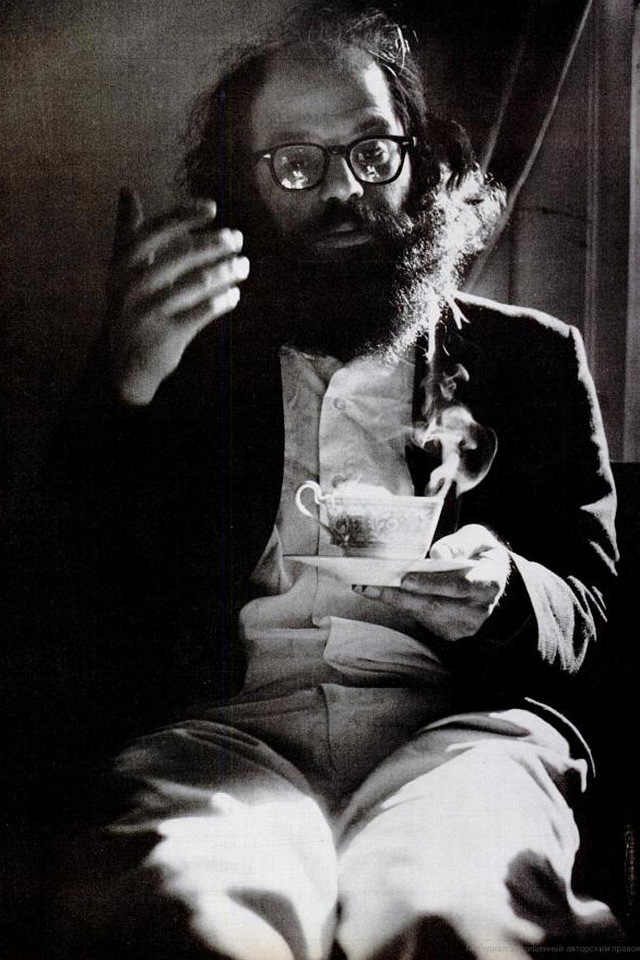

Мэрилин Монро смотрит в объектив одного из самых известных фотографов LIFE

— Альфреда Эйзенштадта , 1953 год.

Кроме постоянных фотокорреспондентов, авторами LIFE

становились и сторонние фотографы — одним из них стал личный фотограф Адольфа Гитлера, немец Хуго Йегер . Архив Йегера, состоящий из нескольких тысяч цветных снимков, на которых запечатлен фюрер во времена своей бурной военно-политической деятельности, а также его окружение и сограждане, был приобретён журналом LIFE

в 1970 году. В апреле 1970 года LIFE

опубликовал серию фотографий Хуго Йегера с комментарием редактора:

“Мы нечасто уделяем в журнале так много места работе человека, которого так мало уважаем”.

Тем не менее, фотографии Йегера представляют большую историческую ценность, так как позволяют прочувствовать атмосферу эпохи, увидеть поближе Гитлера-фюрера и его окружение, представить, как функционировал Третий рейх и пропагандистская машина фашистской Германии.

комментарий LIFE

: “Автомобильный инженер Фердинанд Порше (в костюме), Адольф Гитлер, слева от фюрера — глава Германского трудового фронта Роберт Лей восхищаются подарком Гитлеру на 50-летие: Фольксваген с откидным верхом”, 1939 год, фотограф Хуго Йегер.

Комментарий LIFE

: “Лига немецких девушек, танцующих во время Конгресса партии рейха, 1938, Нюрнберг, Германия”, фотограф Хуго Йегер.

23 ноября 1936 года в печать вышел первый номер журнала «Лайф» (LIFE), который в последующие 30 лет стал символом фотожурналистики. Предлагаем подборку самых ярких фотографий, размещенных на обложке журнала.

Goin’ Home. Photo by Ed Clark, 1945.

Старшина Грэм Джексон играет Goin’ Home на похоронах президента Рузвельта 12 апреля 1945 года.

Американский образ жизни (The American Way). Photo by Margaret Bourke-White, 1937.

Очередь за едой у пункта Красного Креста во время Великой депрессии на фоне плаката «Нет такого другого образа жизни, как американский».

Марлен Дитрих (Marlene Dietrich). Photo by Milton Greene, 1952.

Самый длинный день (The Longest Day). Photo by Robert Capa, 1944.

Момент высадки американской армии на Омаха-бич в Нормандии 6 июня 1944 года, отображенной также в фильме «Спасти рядового Райана» Стивена Спилберга.

Глаза ненависти (Eyes of Hate). Photo by Alfred Eisenstaedt, 1933.

Здесь запечатлен момент, когда Геббелс (сидит) узнал, что его переводчик — еврей, и приветливая улыбка сошла с его лица.

Meeting peace With fire hoses. Photo by Charles Moore, 1963.

Разгон мирного митинга против сегрегации в Бирмингеме (штат Алабама) с помощью пожарных брандспойтов.

The Marlboro Man. Photo by Leonard McCombe, 1949.

39-летний техасский ковбой Кларенс Хэйли, образ которого был впоследствии использован для рекламы сигарет.

Peek-A-Boo. Photo by Ed Clark, 1958.

Джон Кеннеди со своей дочерью Кэролайн, одна из легендарных фотографий журнала LIFE.

Песок Иводзимы (Sand of Iwo Jima). Photo by Photo by W. Eugene Smith, 1945.

Американские морские пехотинцы во время битвы за Иводзиму весной 1945 года.

Освобождение Бухенвальда (Liberation of Buchenwald). Photo by Margaret Bourke-White, 1945.

Великая душа (The Great Soul). Photo by Margaret Bourke-White, 1946.

Махатма Ганди рядом с его прялкой — символом ненасильственного движения за независимость Индии от Великобритании.

A Child Is Born. Photo by Lennart Nilsson, 1965.

В утробе матери.

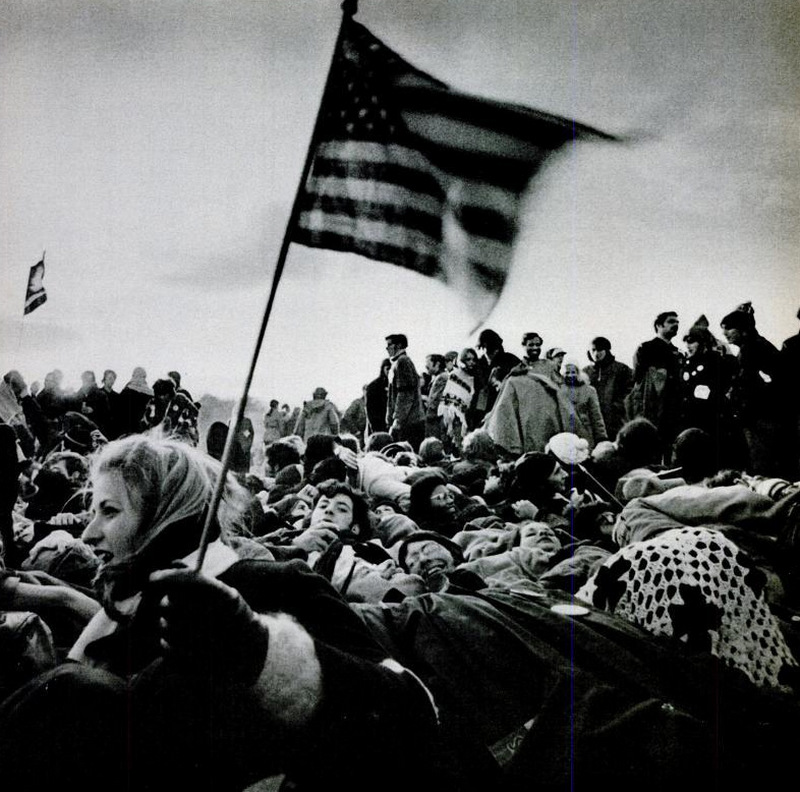

Всадники свободы (Freedom Riders). Photo by Paul Schutzer, 1961.

«Всадники свободы» (Freedom Riders) — совместные автобусные поездки черных и белых активистов, протестовавших против нарушений прав чернокожего населения в южных штатах США. В 1961 г. они арендовали автобусы и разъезжали по южным штатам, выступая против сегрегационных законов и обычаев, подвергаясь нападениям со стороны белых южан и арестам. Для защиты активистов в ходе поездки из Монтгомери (штат Алабама) в Джексоне (штат Миссисипи) были выделены солдаты Национальной гвардии.

Агония (Agony): Photo by Ralph Morse, 1944.

Армейский медик Джордж Лотт, тяжело раненный в обе руки.

Море шляп (Sea of Hats). Photo by Margaret Bourke-White, 1930.

В Нью-Йорке.

Reaching Out: Photo by Larry Burrows, 1966.

Морские пехотинцы во время войны во . Темнокожий солдат тянется к своему раненому белому товарищу.

Alexander Solzhenitsyn Breathes Free. Photo by Harry Benson.

«Свободное дыхание». Александр Солженицын в Вермонте.

Королевские прыжки (Jumping Royals). Photo by Philippe Halsman, 1959.

Герцог и герцогиня Виндзор.

В центре внимания (Center of Attention). Photo by Leonard McCombe, 1956.

Лицо смерти (Face of Death). Photo by Ralph Morse, 1943.

Голова японского солдата на танке.

Пикассо и кентавр (Picasso and Centaur). Photo by Gjon Mili, 1949.

Эфемерный рисунок воздухе.

Уинстон Черчилль (Winston Churchill). Photo by Yousuf Karsh, 1941.

Премьер-министр Великобритании в 1940-1945 и 1951-1955 годах. Политик, военный, журналист, писатель, лауреат Нобелевской премии по литературе.

Барабанщик из Мичиганского университета марширует с детьми.

Пилот реактивного самолета.

На кукольном представлении в парижском парке, момент убийства змея Святым Георгием.

На просмотре первого полнометражного стереофильма Bwana Devil.

Актер Стив Маккуин («Великолепная семерка»).

Сельский доктор Эрнест Кериани, единственный врач на 1200 квадратных миль региона, после неудачной операции кесарева сечения, в ходе которой из-за осложнений погибли мать и ребенок.

Американские солдаты, погибшие в результате боя с японцами на пляже в Новой Гвинее. Первый снимок с мертвыми американскими солдатами на поле боя в ходе Второй мировой.

Джон Кеннеди (тогда еще сенатор) со своим младшим братом Робертом в гостиничном номере во время съезда Демократической партии в Лос-Анджелесе. Оба будут убиты через несколько лет.

В фильме «Брак по-итальянски». Когда этот откровенный снимок украсил обложку «Лайф», многие критиковали журнал за то, что он «опустился до порнографии». Один читатель написал: «Слава богу, что почтальон приходит в полдень, когда мои дети в школе».

63-летний Чарли Чаплин.

Шведская прыгунья в высоту Гунхильд Ларкин на Олимпийских играх в Мельбурне (Австралия) 1956 года.

Подборка знаменитых фотографий журнала «LIFE», в разные годы публиковавшихся на его обложке. «LIFE» – Еженедельный новостной журнал, выходивший с 1936 до 1972 гг., с сильным акцентом на фото журналистику. Затем выходил ежемесячно с 1978 по 2000 год.

1. Кукольное представление (The Puppet Show). Photo by Alfred Eisenstaedt, 1963

На кукольном представлении в парижском парке, момент убийства змея Святым Георгием.

2. Goin’ Home. Photo by Ed Clark, 1945

Старшина Грэм Джексон играет «Goin’ Home» на похоронах президента Рузвельта 12 апреля 1945 года.

3. Американский образ жизни (The American Way). Photo by Margaret Bourke-White, 1937

Очередь за едой у пункта Красного креста во время Великой депресии на фоне плаката: «Нет такого другого образа жизни, как американский».

.jpg)

4. Марлен Дитрих (Marlene Dietrich). Photo by Milton Greene, 1952

5. Самый длинный день (The Longest Day). Photo by Robert Capa, 1944

Момент высадки американской армии на Омаха-бич в Нормандии 6 июня 1944 года, отображенной также в фильме «Спасти рядового Райана» Стивена Спилберга.

6. Глаза ненависти (Eyes of Hate). Photo by Alfred Eisenstaedt, 1933

Здесь запечатлен момент, когда Геббелс (сидит) узнал, что его переводчик — еврей и приветливая улыбка

сошла с его лица.

7. Meeting peace With fire hoses. Photo by Charles Moore, 1963

Разгон мирного митинга против сегрегации в Берменгеме (штат Алабама) с помощью пожарных брандспойтов (fire hoses).

8. «The Marlboro Man». Photo by Leonard McCombe, 1949

39-летний техасский ковбой Clarence Hailey, образ которого был использован впоследствии для рекламы сигарет.

9. Peek-A-Boo. Photo by Ed Clark, 1958

Джон Кеннеди со своей дочерью Керролайн, одна из легендарных фотографий журнала Life

10. Песок Иводзимы (Sand of Iwo Jima). Photo by Photo by W. Eugene Smith, 1945

Американские морские пехотинцы во время битвы за Иводзиму весной 1954

11. Освобождение Бухенвальда (Liberation of Buchenwald). Photo by Margaret Bourke-White, 1945

12. Великая душа (The Great Soul). Photo by Margaret Bourke-White, 1946

Махатма Ганди рядом с его прялкой — символом ненасильственного движения за независимость Индии от Великобритании.

13. A Child Is Born. Photo by Lennart Nilsson, 1965

Первый в истории снимок ребенка в утробе матери.

14. Всадники свободы (Freedom Riders). Photo by Paul Schutzer, 1961 «Всадники свободы» (Freedom Riders) — совместные автобусные поездки черных и белых активистов, протестовавших против нарушений прав чернокожего населения в южных шт. США. В 1961 г. они арендовали автобусы и разъезжали по юж. штатам, выступая против сегрегационных законов и обычаев, подвергаясь нападениям со стороны белых южан и арестам. Для защиты активистов в ходе поездки из из Монтгомери (штат Алабама) в Джексоне (штат Миссисипи) были выделены солдаты Национальной гвардии.

15. Агония (Agony): Photo by Ralph Morse, 1944

Армейский медик Джордж Лотт, тяжело раненный в обе руки.

.jpg)

16. Море шляп (Sea of Hats). Photo by Margaret Bourke-White, 1930

В Нью-Йорке.

17. Reaching Out: Photo by Larry Burrows, 1966

Морские пехотинцы во время войны во Вьетнаме. Темнокожий солдат тянется к своему раненому белому товарищу.

18. Alexander Solzhenitsyn Breathes Free. Photo by Harry Benson

Свободное дыхание. Александр Солженицын в Вермонте

19. Королевские прыжки (Jumping Royals). Photo by Philippe Halsman, 1959

Герцог и герцогиня Виндзор

20. В центре внимания (Center of Attention). Photo by Leonard McCombe, 1956

21. Лицо смерти (Face of Death). Photo by Ralph Morse, 1943

Голова японского солдата на танке

22. Пикассо и кентавр (Picasso and Centaur). Photo by Gjon Mili, 1949

Эфемерный рисунок воздухе.

23. Уинстон Черчилль (Winston Churchill). Photo by Yousuf Karsh, 1941

Премьер-министр Великобритании в 1940-1945 и 1951-1955 годах. Политик, военный, журналист, писатель, лауреат Нобелевской премии по литературе.

24. Леопард-убийца (A Leopard’s Kill). Photo by John Dominis, 1966

25. Крысолов из Энн-Арбор (Pied Piper of Ann Arbor). Photo by Alfred Eisenstaedt, 1950

Барабанщик из Мичиганского университета марширует с детьми

26. Человек реактивного века (Jet Age Man). Photo by Ralph Morse, 1954

Пилот реактивного самолета

27. 3D Movie Audience. Photo by J.R. Eyerman, 1952

На просмотре первого полнометражного стерео-фильма Bwana Devil.

28. Steve McQueen. Photo by John Dominis, 1963

Актер Стив Маккуин («Великолепная семерка»).

29. Сельский врач (Country Doctor). Photo by W. Eugene Smith, 1948

Сельский доктор Ernest Ceriani, единственный врач на 1200 квадратных миль региона, после неудачной операции кесарева сечения, в ходе которой из-за осложнений погибли мать и ребенок.

30. Три американца (Three Americans). Photo by George Strock, 1943

Американские солдаты, погибшие в результате боя с японцами на пляже в Новой Гвинее. Первый снимок с мертвыми американскими солдатами на поле боя в ходе Второй мировой.

31. Jack and Bobby: Photo by Hank Walker, 1960

Джон Кеннеди (тогда еще сенатор) со своим младшим братом Робертом в гостиничном номере во время съезда Демократической партии в Лос-Анджелесе. Оба будут убиты через несколько лет.

32. Sophia Loren. Photo by Alfred Eisenstaedt, 1966

Софи Лорен в фильме «Брак по-итальянски». Когда это откровенный снимок украсил обложку «Лайф», многие

критиковали журнал за то, что он «опустился до порнографии». Один читатель написал: «Слава Богу, что почтальон приходит в полдень, когда мои дети в школе».

33. Charlie Chaplin. Photo by W. Eugene Smith, 1952

63-летний Чарли Чаплин

34. Gunhild Larking. Photo by George Silk, 1956

Шведская прыгунья в высоту Gunhild Larking на Олимпийских играх в Мельбурне (Австралия) 1956 года

35. The Beatles in Miami. Photo by John Loengard, 1964

Битлз во время американских гастролей. Вода в бассейне была довольно холодной в тот день, о чем свидетельствует гримаса Ринго.

36. Перед свадьбой (Before the Wedding). Photo by Michael Rougier, 1962

37. Оставшийся в живых (Littlest Survivor). Photo by W. Eugene Smith, 1943

Во время Второй мировой сотни японцев оказались в осаде на острове Сайпан и совершили массовое самоубийство, чтобы не сдаваться американцам. Когда американские морские пехотинцы осматривали остров, в одной из пещер был найден едва живой ребенок.

38. Liz and Monty: Photo by Peter Stackpole, 1950

Элизабет Тейлор и Монтгомери Клифт во время перерыва на съемках фильма «A Place in the Sun» на студии Paramount.

39. «Dali Atomicus». Photo by Philippe Halsman, 1948

Шесть часов и 28 бросков (воды, стула и трех кошек). По словам фотографа «его помощники и он были мокрыми, грязными и почти полностью истощенными», когда наконец снимок удался.

40. Both Sides Now. Photo by John Shearer, 1971

Мухаммед Али любил перед боем дразнить оппонентов. Перед «боем века» с Джо Фрейзером в марте 71 года

он подверг сомнению его мужественность, интеллектуальные способности и «чернокожесть».

.jpg)

41. Ingenue Audrey: Photo by Mark Shaw, 1954

25-летняя звезда «Римских каникул» Одри Хепберн

42. Лев зимой (Lion in Winter). Photo by John Bryson, 1959

Хемингуэй неподалеку от своего дома в Кетчуме (шт. Айдахо)

43. Расступление моря в Солт-Лейк-Сити (Parting the Sea in Salt Lake City). Photo by J.R. Eyerman, 1958

Автокинотеатр в столице штата Юта Солт-Лейк-Сити. На экране Моисей перед расступающимся Красным морем в фильме «Десять заповедей».

44. Побег мальчика (A Boy’s Escape). Photo by Ralph Crane, 1947

Постановочное фото, изображающее побег мальчика из детского дома.

45. Перед Камелотом, визит в Западную Вирджинию (Before Camelot, a Visit to West Virginia). Photo by Hank Walker, 1960

Джон Кеннеди, который вскоре станет самым молодым американским президентом, выступает в каком-то городке во время предвыборной компании.

46. Самолет над Манхеттеном (Airplane Over Manhattan). Photo by Margaret Bourke-White, 1939

47. На свет (Into the Light). Photo by Eugene Smith, 1946

48. Прыжок одинокого волка (A Wolf’s Lonely Leap). Photo by Jim Brandenburg, 1986

Борьба полярного волка за выживание на севере Канады.

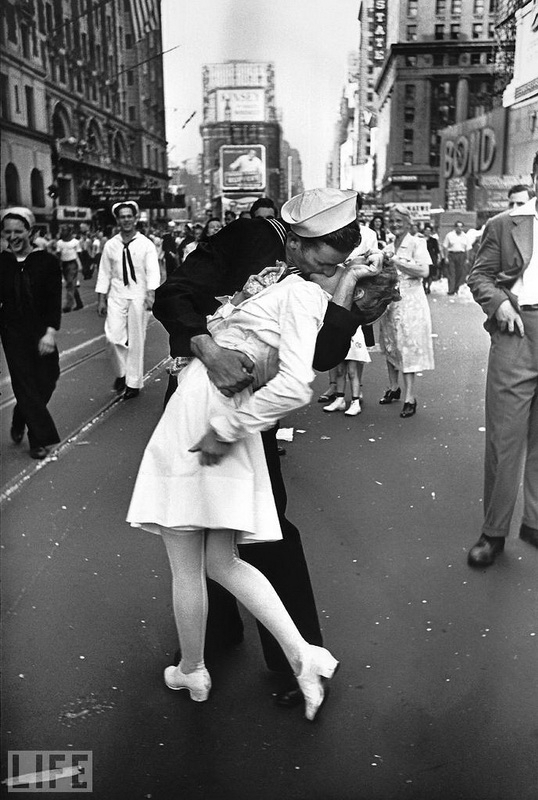

49. Поцелуй (The Kiss). Photo by Alfred Eisenstaedt, 1945

Одна из самых известных фотографий. Поцелуй моряка и медсестры после объявления об окончании войны.

Автор:

25 ноября 2013 08:48

Журнал Life — еженедельный новостной журнал, который был основан в 1936 году Генри Люсом. За всю историю своего существования ( а это без малого 40 лет) в его архивах накопилось великое множество самых различных уникальный фотографий, многие из которых в дальнейшем стали настоящими легендами. Вашему вниманию предлагается подборка уникальных снимков, которые размещались на его обложке.

Peek-A-Boo. Photo by Ed Clark, 1958

Джон Кеннеди со своей дочерью Керролайн, одна из легендарных фотографий журнала Life

Кукольное представление (The Puppet Show). Photo by Alfred Eisenstaedt, 1963

На кукольном представлении в парижском парке, момент убийства змея Святым Георгием.

Goin’ Home. Photo by Ed Clark, 1945

Старшина Грэм Джексон играет «Goin’ Home» на похоронах президента Рузвельта 12 апреля 1945 года.

Американский образ жизни (The American Way). Photo by Margaret Bourke-White, 1937

Очередь за едой у пункта Красного креста во время Великой депресии на фоне плаката: «Нет такого другого образа жизни, как американский».

Марлен Дитрих (Marlene Dietrich). Photo by Milton Greene, 1952

Самый длинный день (The Longest Day). Photo by Robert Capa, 1944

Момент высадки американской армии на Омаха-бич в Нормандии 6 июня 1944 года, отображенной также в фильме «Спасти рядового Райана» Стивена Спилберга.

Глаза ненависти (Eyes of Hate). Photo by Alfred Eisenstaedt, 1933

Здесь запечатлен момент, когда Геббелс (сидит) узнал, что его переводчик — еврей и приветливая улыбка сошла с его лица.

Meeting peace With fire hoses. Photo by Charles Moore, 1963

Разгон мирного митинга против сегрегации в Берменгеме (штат Алабама) с помощью пожарных брандспойтов (fire hoses).

«The Marlboro Man». Photo by Leonard McCombe, 1949

39-летний техасский ковбой Clarence Hailey, образ которого был использован впоследствии для рекламы сигарет.

Песок Иводзимы (Sand of Iwo Jima). Photo by Photo by W. Eugene Smith, 1945

Американские морские пехотинцы во время битвы за Иводзиму весной 1945 года

Освобождение Бухенвальда (Liberation of Buchenwald). Photo by Margaret Bourke-White, 1945

Великая душа (The Great Soul). Photo by Margaret Bourke-White, 1946

Махатма Ганди рядом с его прялкой — символом ненасильственного движения за независимость Индии от Великобритании.

A Child Is Born. Photo by Lennart Nilsson, 1965

Первый в истории снимок ребенка в утробе матери.

Всадники свободы (Freedom Riders). Photo by Paul Schutzer, 1961

«Всадники свободы» (Freedom Riders) — совместные автобусные поездки черных и белых активистов, протестовавших против нарушений прав чернокожего населения в южных шт. США. В 1961 г. они арендовали автобусы и разъезжали по юж. штатам, выступая против сегрегационных законов и обычаев, подвергаясь нападениям со стороны белых южан и арестам. Для защиты активистов в ходе поездки из из Монтгомери ( штат Алабама) в Джексоне ( штат Миссисипи) были выделены солдаты Национальной гвардии.

Агония (Agony): Photo by Ralph Morse, 1944

Армейский медик Джордж Лотт, тяжело раненный в обе руки.

Море шляп (Sea of Hats). Photo by Margaret Bourke-White, 1930

В Нью-Йорке.

Reaching Out: Photo by Larry Burrows, 1966

Морские пехотинцы во время войны во Вьетнаме. Темнокожий солдат тянется к своему раненому белому товарищу.

Alexander Solzhenitsyn Breathes Free. Photo by Harry Benson

Свободное дыхание. Александр Солженицын в Вермонте

Королевские прыжки (Jumping Royals). Photo by Philippe Halsman, 1959

Герцог и герцогиня Виндзор

В центре внимания (Center of Attention). Photo by Leonard McCombe, 1956

Пикассо и кентавр (Picasso and Centaur). Photo by Gjon Mili, 1949

Эфемерный рисунок воздухе.

Уинстон Черчилль (Winston Churchill). Photo by Yousuf Karsh, 1941

Премьер-министр Великобритании в 1940—1945 и 1951—1955 годах. Политик, военный, журналист, писатель, лауреат Нобелевской премии по литературе.

Леопард-убийца (A Leopard’s Kill). Photo by John Dominis, 1966

Крысолов из Энн-Арбор (Pied Piper of Ann Arbor). Photo by Alfred Eisenstaedt, 1950

Барабанщик из Мичиганского университета марширует с детьми

Человек реактивного века (Jet Age Man). Photo by Ralph Morse, 1954

Пилот реактивного самолета

3D Movie Audience. Photo by J.R. Eyerman, 1952

На просмотре первого полнометражного стерео-фильма Bwana Devil.

Steve McQueen. Photo by John Dominis, 1963

Актер Стив Маккуин («Великолепная семерка»).

Сельский врач (Country Doctor). Photo by W. Eugene Smith, 1948

Сельский доктор Ernest Ceriani, единственный врач на 1200 квадратных миль региона, после неудачной операции кесарева сечения, в ходе которой из-за осложнений погибли мать и ребенок.

Три американца (Three Americans). Photo by George Strock, 1943

Американские солдаты, погибшие в результате боя с японцами на пляже в Новой Гвинее. Первый снимок с мертвыми американскими солдатами на поле боя в ходе Второй мировой.

Jack and Bobby: Photo by Hank Walker, 1960

Джон Кеннеди (тогда еще сенатор) со своим младшим братом Робертом в гостиничном номере во время съезда Демократической партии в Лос-Анджелесе. Оба будут убиты через несколько лет.

Sophia Loren. Photo by Alfred Eisenstaedt, 1966

Софи Лорен в фильме «Брак по-итальянски». Когда это откровенный снимок украсил обложку «Лайф», многие критиковали журнал за то, что он «опустился до порнографии». Один читатель написал: «Слава Богу, что почтальон приходит в полдень, когда мои дети в школе».

Charlie Chaplin. Photo by W. Eugene Smith, 1952

63-летний Чарли Чаплин

Gunhild Larking. Photo by George Silk, 1956

Шведская прыгунья в высоту Gunhild Larking на Олимпийских играх в Мельбурне (Австралия) 1956 года

The Beatles in Miami. Photo by John Loengard, 1964

Битлз во время американских гастролей. Вода в бассейне была довольно холодной в тот день, о чем свидетельствует гримаса Ринго.Перед свадьбой (Before the Wedding). Photo by Michael Rougier, 1962

Перед свадьбой (Before the Wedding). Photo by Michael Rougier, 1962

Оставшийся в живых (Littlest Survivor). Photo by W. Eugene Smith, 1943

Во время Второй мировой сотни японцев оказались в осаде на острове Сайпан и совершили массовое самоубийство, чтобы не сдаваться американцам. Когда американские морские пехотинцы осматривали остров, в одной из пещер был найден едва живой ребенок.

Liz and Monty: Photo by Peter Stackpole, 1950

Элизабет Тейлор и Монтгомери Клифт во время перерыва на съемках фильма «A Place in the Sun» на студии Paramount.

Dali Atomicus». Photo by Philippe Halsman, 1948

Шесть часов и 28 бросков (воды, стула и трех кошек). По словам фотографа «его помощники и он были мокрыми, грязными и почти полностью истощенными», когда наконец снимок удался.

Both Sides Now. Photo by John Shearer, 1971

Мухаммед Али любил перед боем дразнить оппонентов. Перед «боем века» с Джо Фрейзером в марте 71 года он подверг сомнению его мужественность, интеллектуальные способности и «чернокожесть».

. Ingenue Audrey: Photo by Mark Shaw, 1954

25-летняя звезда «Римских каникул» Одри Хепберн

Лев зимой (Lion in Winter). Photo by John Bryson, 1959

Хемингуэй неподалеку от своего дома в Кетчуме (шт. Айдахо)

. Расступление моря в Солт-Лейк-Сити (Parting the Sea in Salt Lake City). Photo by J.R. Eyerman, 1958

Автокинотеатр в столице штата Юта Солт-Лейк-Сити. На экране Моисей перед расступающимся Красным морем в фильме «Десять заповедей».

Побег мальчика (A Boy’s Escape). Photo by Ralph Crane, 1947

Постановочное фото, изображающее побег мальчика из детского дома.

Перед Камелотом, визит в Западную Вирджинию (Before Camelot, a Visit to West Virginia). Photo by Hank Walker, 1960

Джон Кеннеди, который вскоре станет самым молодым американским президентом, выступает в каком-то городке во время предвыборной компании.

Самолет над Манхеттеном (Airplane Over Manhattan). Photo by Margaret Bourke-White, 1939

На свет (Into the Light). Photo by Eugene Smith, 1946

Прыжок одинокого волка (A Wolf’s Lonely Leap). Photo by Jim Brandenburg, 1986

Борьба полярного волка за выживание на севере Канады.

Поцелуй (The Kiss). Photo by Alfred Eisenstaedt, 1945

Одна из самых известных фотографий. Поцелуй моряка и медсестры после объявления об окончании войны.

Dennis Stock: Photo by Andreas Feininger, 1951

Источник:

Ссылки по теме:

Новости партнёров

реклама

Журнал LIFE – это уникальные снимки и оригинальная подача кадров. Архив издания насчитывает приблизительно 10 миллионов уникальных фотографий, которые журнал накопил за всю историю своего существования.

Популярность журнала LIFE объясняется тем, что его, если можно так выразиться, мультимедийное оформление, было доведено до совершенства. Любые события, новости, обзоры журнала сопровождались прекрасно иллюстрированными фотографиями. И это в те времена, когда телевизоры еще не были распространены повсеместно. Просмотр и чтение LIFE было для американцев куда более увлекательным занятием, нежели просмотр телевизионных новостей. Фотосъемки для журнала производились по всему миру лучшими мастерами. События, которые происходили в США и других странах, были представлены профессиональными очерками с качественными фотоснимками.

Огромный архив профессиональных фотоснимков компания выложила в свободный доступ через новый сервис Google. При этом для каждой фотографии указываются точные данные: дата и место съемки, кем сделан снимок и что на нем изображено. Многие из этих фотографий ранее вообще не были нигде опубликованы. Конечно, это не весь архив журнала LIFE, однако, он уже насчитывает несколько миллионов фото и постоянно пополняется.

Девиз первого выпуска LIFE: «Есть жизнь – есть надежда»

Основатель журнала LIFE − Джон Эймс Митчел. Впервые он вышел в печать в 1836 году. LIFE изначально позиционировал себя как развлекательное издание: социальные комментарии, шутки. В журнале работали достаточно знаменитые в своих кругах писатели и карикатуристы: Чарльз Дана Гибсон, Норман Рокуэлл и Гарри Оливер.

В 1918 году Митчел умер. Журнал перекупил за 1 миллион американских долларов Чарльз Гибсон. Но несмотря на гениальный персонал, LIFE неизбежно катился к финансовому краху.

Почему?

Семейный юмор и милые аккуратненькие шуточки на социальную тему канули в Лету, общество обросло цинизмом и вырос интерес к сексуальной тематике.

Во времена Великой депрессии журнал потерял большую долю своих читателей. Зато популярность набрали журналы New Yorker, Ballyhoo и Hooey за счет непристойного юмора.

В 1936 году Генри Льюис ( владелец газеты Times) выкупил LIFE за 92 милилона долларов, а сделал он это, чтобы получить права на имя журнала.

В период Генри Льюса LIFE стал первым полностью фотографическим американским журналом новостей. Вклад в американскую фотожурналистику этого издания невозможно сравнивать с чем-либо.

Пожалуй, его самой знаменитой фотографией стала «Медсестра в объятиях моряка» от 27 августа 1945 года, снятая Альфредом Эйзенштадтом в Нью-Йорке во время празднования победы над Японией.

Журнал неоднократно менял формат и закрывался: с 1936 года до его закрытия в 1972 году это был еженедельник. В 1978 году после шестилетнего перерыва его выпуск был возобновлён, но уже в формате ежемесячного издания.

В 2000 году журнал LIFE прекратил свое существование.

Что удивительно: американский журналист Джордж Стори родился чуть ли не в один день с журналом LIFE в 1936 году. В первом номере LIFE появилась фотография новорожденного Джорджа с подзаголовком «Жизнь начинается». В дальнейшем судьба Стори периодически освещалась на страницах журнала − две его женитьбы, отцовство, уход на пенсию. 64-летний Джордж появился и в последнем выпуске, в мае 2000 года, на этот раз под заголовком «Жизнь заканчивается» (имелось в виду закрытие журнала). Через несколько дней Джордж Стори скончался от инфаркта.

Однако с 2004 по 2007 год LIFE выходил как еженедельное приложение к газетам The Los Angeles Times, The Miami Herald и The Washington Post.

В 2007 году Time Inc. прекратила бумажную публикацию журнала, заявив о намерении продолжить издание LIFE исключительно на просторах Интернета. В качестве причины Time Inc. назвала спад газетного бизнеса в целом, а также низкие доходы от рекламы со страниц их журнала. В итоге компания посчитала, что выпускать еженедельное приложение совершенно не выгодно и решила перевести LIFE в электронный формат. Видимо, учитывая большую армию интернет-пользователей и ту возростающую популярность, которой пользуются сейчас мультимедийные интернет-ресурсы, Time Inc. надеется дать журналу «новую жизнь».

Смотрите также:

- 27 неопубликованных фотографий из архивов National Geographic

- Фотографии, которые стоят тысячи слов. 79 архивных снимков от National Geographic

- Фотографии, которые изменили мир: 100 самых значимых снимков по версии журнала Time

![]()

Самая заботливая лисичка в мире.

![]()

Церемония награждения в Торонто была очень скучной, поэтому один из наблюдателей решил ее разнообразить.

![]()

Скажи а-а-а!

![]()

Медведи в парке Сакраменто демонстрируют мастерство баланса и свои пятки.

![]()

На выход!

![]()

Юный стоматолог.

![]()

Чего не сделаешь для лучшего друга!

![]()

Надеясь пристыдить орангутана за лишний вес и посадить на диету, Билл Пекетт, смотритель Лондского зоопарка за обезьянами, показывает мистеру Джиггсу, что обхват его талии равен 119 сантиметрам.

![]()

Белка пьет воду из протекающего крана, Орландо, Флорида, США.

![]()

Ну и как у вас тут, наверху?

![]()

Заботливая ворона.

![]()

Гвардеец демонстрирует, что даже если он упадет, британские солдаты не обратят на это никакого внимания.

![]()

В Музее искусств Сан-Франциско есть кое-что поинтереснее современного искусства.

![]()

Когда очень сильно хочется пить, и решето сойдет в качестве кружки.

![]()

Джен Шлетер ревнует Рикки Лоффи к любой другой женщине, даже если это невеста, на свадьбе которой они находятся.

![]()

Причина, по которой иногда почта не бывает доставлена. Ланкашир, Англия.

![]()

Уборщица на танцах в Лондоне не может сдержаться и тоже пускается в пляс.

![]() Подмигивающий тюлень в зоопарке Копенгагена.

Подмигивающий тюлень в зоопарке Копенгагена.

![]()

Все мы люди, и ничто человеческое нам не чуждо.

![]()

Собачка Сьюзи с Манхеттена, оказывается, гораздо сильнее, чем кажется на первый взгляд.

![]()

А что, в согнутой будке даже удобнее разговаривать!

![]()

Сьюзи Спир из Ла-Порта, Индиана, на своем выпускном балу, что-то нежно «шепчет» своему кавалеру.

![]()

Главное — не спалиться.

![]()

На открытии нового магазина Robrt Hall в Мемфисе пиджак 39-го размера помогает продать себя.

![]()

В великой индийской пустыне к северу от города Джодхпур, где воды не хватает, она подается из высоких кранов и стоит 2,5 цента за мешок.

![]()

Кэти соблюдает закон о наличии шлема на голове во время езды на мотоцикле с Франклином Дрисколлом на Гаваях.

![]()

В зоопарк Проспект-парка в Бруклине, баран Барбари карабкается по стене, мечтая вместо этого подниматься на высокие скалы на его африканской родине.

![]()

Десятилетний Ch.Mighty Mo II из Флоссмура, Иллинойс.

![]()

Я тут постою?

![]()

Сел пообедать с хозяином.

![]()

Шляпа из трубы сузафона.

![]()

Когда рук уже не хватает, десятилетний почтальон Филлип Лаффин из Эллсворта, Мэн, держит почту зубами.

![]()

Тоггл даже не студент школы в Шампайн, штат Иллинойс, но все равно участвует в забеге учеников на милю.

![]()

Нет, не упадет.

![]()

Жизнь прекрасна, улыбайтесь почаще!

Источник: интернет

| |

A cover of the earlier Life magazine from 1911 | |

| Editor | George Cary Eggleston |

|---|---|

| Former editors | Robert E. Sherwood |

| Categories | Humor, general interest |

| Frequency | Weekly |

| Publisher | Clair Maxwell (1921–1942) |

| Total circulation (1920) | 250,000 |

| First issue | January 4, 1883; 140 years ago |

| Final issue | 2000 |

| Country | United States |

| Based in | New York City, New York, U.S. |

| Language | English |

| Website | www.life.com |

| ISSN | 0024-3019 |

Life was an American magazine published weekly from 1883 to 1972, as an intermittent «special» until 1978, and as a monthly from 1978 until 2000. During its golden age from 1936 to 1972, Life was a wide-ranging weekly general-interest magazine known for the quality of its photography, and was one of the most popular magazines in the nation, regularly reaching one-quarter of the population.[1]

Life was independently published for its first 53 years until 1936 as a general-interest and light entertainment magazine, heavy on illustrations, jokes, and social commentary. It featured some of the most notable writers, editors, illustrators and cartoonists of its time: Charles Dana Gibson, Norman Rockwell and Jacob Hartman Jr. Gibson became the editor and owner of the magazine after John Ames Mitchell died in 1918. During its later years, the magazine offered brief capsule reviews (similar to those in The New Yorker) of plays and movies currently running in New York City, but with the innovative touch of a colored typographic bullet resembling a traffic light, appended to each review: green for a positive review, red for a negative one, and amber for mixed notices.

In 1936, Time publisher Henry Luce bought Life, only wanting its title: he greatly re-made the publication. Life (now stylized in all caps) became the first all-photographic American news magazine, and it dominated the market for several decades, with a circulation of more than 13.5 million copies a week at one point. Possibly the best-known image published in the magazine was Alfred Eisenstaedt’s photograph of a nurse in a sailor’s arms, taken on August 14, 1945 during a VJ-Day celebration in New York’s Times Square. The magazine’s role in the history of photojournalism is considered its most important contribution to publishing. Its profile was such that the memoirs of President Harry S. Truman, Prime Minister Winston Churchill, and General Douglas MacArthur were all serialized in its pages.

After 2000, Time Inc. continued to use the Life brand for special and commemorative issues. Life returned to regularly scheduled issues when it became a weekly newspaper supplement from 2004 to 2007.[2] The website life.com, originally one of the channels on Time Inc.’s Pathfinder service, was for a time in the late 2000s managed as a joint venture with Getty Images under the name See Your World, LLC.[3] On January 30, 2012, the Life.com URL became a photo channel on Time.com.[clarification needed][2][4]

1883 humor and general interest magazine[edit]

Cover art, January 27, 1910, illustration by Coles Phillips in original Life magazine

Cover of issue for January 24, 1924

Life was founded on January 4, 1883, in a New York City artist’s studio at 1155 Broadway, as a partnership between John Ames Mitchell and Andrew Miller. Mitchell held a 75% interest in the magazine with the remaining 25% held by Miller. Both men retained their holdings until their deaths.[5] Miller served as secretary-treasurer of the magazine and managed the business side of the operation. Mitchell, a 37-year-old illustrator who used a $10,000 inheritance to invest in the weekly magazine, served as its publisher. He also created the first Life name-plate with cupids as mascots and later on, drew its masthead of a knight leveling his lance at the posterior of a fleeing devil. Then he took advantage of a new printing process using zinc-coated plates, which improved the reproduction of his illustrations and artwork. This edge helped because Life faced stiff competition from the best-selling humor magazines Judge and Puck, which were already established and successful. Edward Sandford Martin was brought on as Life‘s first literary editor; the recent Harvard University graduate was a founder of the Harvard Lampoon.

The motto of the first issue of Life was: «While there’s Life, there’s hope.»[6] The new magazine set forth its principles and policies to its readers:

We wish to have some fun in this paper…We shall try to domesticate as much as possible of the casual cheerfulness that is drifting about in an unfriendly world…We shall have something to say about religion, about politics, fashion, society, literature, the stage, the stock exchange, and the police station, and we will speak out what is in our mind as fairly, as truthfully, and as decently as we know how.[6]

The magazine was a success and soon attracted the industry’s leading contributors,[7] of which the most important was Charles Dana Gibson. Three years after the magazine was founded, the Massachusetts native first sold Life a drawing for $4: a dog outside his kennel howling at the moon. Encouraged by a publisher, also an artist, Gibson was joined in Life early days by illustrators such as Palmer Cox (creator of the Brownie), A. B. Frost, Oliver Herford and E. W. Kemble. Life‘s literary roster included the following: John Kendrick Bangs, James Whitcomb Riley and Brander Matthews.

Mitchell was accused of anti-Semitism at a time of high rates of immigration to New York of eastern European Jews. When the magazine blamed the theatrical team of Klaw & Erlanger for Chicago’s Iroquois Theater Fire in 1903, many people complained. Life‘s drama critic, James Stetson Metcalfe, was barred from the 47 Manhattan theatres controlled by the Theatrical Syndicate. Life published caricatures of Jews with large noses.

Several individuals would publish their first major works in Life. In 1908 Robert Ripley published his first cartoon in Life, 20 years before his Believe It or Not! fame. Norman Rockwell’s first cover for Life magazine, Tain’t You, was published May 10, 1917. His paintings were featured on Life‘s cover 28 times between 1917 and 1924. Rea Irvin, the first art director of The New Yorker and creator of the character «Eustace Tilley», began his career by drawing covers for Life.

This version of Life took sides in politics and international affairs, and published pro-American editorials. After Germany attacked Belgium in 1914, Mitchell and Gibson undertook a campaign to push the U.S. into the war. Gibson drew the Kaiser as a bloody madman, insulting Uncle Sam, sneering at crippled soldiers, and shooting Red Cross nurses.

Following Mitchell’s death in 1918, Gibson bought the magazine for $1 million, but the end of World War I had brought on social change. Life‘s brand of humor was outdated, as readers wanted more daring and risque works, and Life struggled to compete. A little more than three years after purchasing Life, Gibson quit and turned the decaying property over to publisher Clair Maxwell and treasurer Henry Richter. Gibson retired to Maine to paint and lost interest in the magazine.

1922 cover, The Flapper by F. X. Leyendecker

In 1920, Gibson selected former Vanity Fair staffer Robert E. Sherwood as editor. A WWI veteran and member of the Algonquin Round Table, Sherwood tried to inject sophisticated humor onto the pages. Life published Ivy League jokes, cartoons, flapper sayings and all-burlesque issues. Beginning in 1920, Life undertook a crusade against Prohibition. It also tapped the humorous writings of Frank Sullivan, Robert Benchley, Dorothy Parker, Franklin Pierce Adams and Corey Ford. Among the illustrators and cartoonists were Ralph Barton, Percy Crosby, Don Herold, Ellison Hoover, H. T. Webster, Art Young and John Held, Jr.

Life had 250,000 readers in 1920,[citation needed] but as the Jazz Age rolled into the Great Depression, the magazine lost money and subscribers. By the time Maxwell and editor George Eggleston took over, Life had switched from publishing weekly to monthly. The two men went to work revamping its editorial style to meet the times, which resulted in improved readership. However, Life had passed its prime and was sliding toward financial ruin. The New Yorker, debuting in February 1925, copied many of the features and styles of Life; it recruited staff from its editorial and art departments.[original research?] Another blow to Life‘s circulation came from raunchy humor periodicals such as Ballyhoo and Hooey, which ran what can be termed «outhouse» gags. In 1933, Esquire joined Life‘s competitors. In its final years, Life struggled to make a profit.

Announcing the end of Life, Maxwell stated: «We cannot claim, like Mr. Gene Tunney, that we resigned our championship undefeated in our prime. But at least we hope to retire gracefully from a world still friendly.»[citation needed]

For Life‘s final issue in its original format, 80-year-old Edward Sandford Martin was recalled from editorial retirement to compose its obituary. He wrote:

That Life should be passing into the hands of new owners and directors is of the liveliest interest to the sole survivor of the little group that saw it born in January 1883 … As for me, I wish it all good fortune; grace, mercy and peace and usefulness to a distracted world that does not know which way to turn nor what will happen to it next. A wonderful time for a new voice to make a noise that needs to be heard![6]

1936 weekly news magazine[edit]

Cover of the June 19, 1944, issue of Life with Gen. Dwight D. Eisenhower. The issue contained 10 frames by Robert Capa of the Normandy invasion. | |

| Editor-in-chief | Edward Kramer Thompson |

|---|---|

| Categories | News |

| Frequency | Weekly (1936–1972) Monthly (1978–2000) |

| Publisher | Henry Luce |

| Total circulation (1937) | 1,000,000 |

| First issue | November 23, 1936; 86 years ago |

| Final issue | May 2000 |

| Company | Time Inc. |

| Country | United States |

| Based in | New York City, New York, U.S. |

| Language | English |

| Website | www.life.com |

| ISSN | 0024-3019 |

In 1936, publisher Henry Luce paid $92,000 (worth $1.43 million in 2021) to the owners of Life magazine because he sought the name for his company, Time Inc. Time Inc. sold Life‘s subscription list, features, and goodwill to Judge. Convinced that pictures could tell a story instead of just illustrating text, Luce launched the new Life on November 23, 1936, along with John Shaw Billings and Daniel Longwell as founding editors.[8][9] The third magazine published by Luce, after Time in 1923 and Fortune in 1930, Life developed as the definitive photo magazine in the U.S., giving as much space and importance to images as to words. The first issue of Life, which sold for ten cents (worth $1.95 in 2021), featured five pages of Alfred Eisenstaedt’s photographs.

In planning the weekly news magazine, Luce circulated a confidential prospectus,[10] within Time Inc. in 1936, which described his vision for the new Life magazine, and what he viewed as its unique purpose. Life magazine was to be the first publication, with a focus on photographs, that enabled the American public,

To see life; to see the world; to eyewitness great events; to watch the faces of the poor and the gestures of the proud; to see strange things — machines, armies, multitudes, shadows in the jungle and on the moon; to see man’s work — his paintings, towers and discoveries; to see things thousands of miles away, things hidden behind walls and within rooms, things dangerous to come to; the women that men love and many children; to see and take pleasure in seeing; to see and be amazed; to see and be instructed…

- —Prospectus for a New Magazine[11][12]

Luce’s first issue cover depicted the Fort Peck Dam in Montana, a Works Progress Administration project, photographed by Margaret Bourke-White.[13]

The format of Life in 1936 was a success: the text was condensed into captions for 50 pages of photographs. The magazine was printed on heavily coated paper and cost readers only a dime. The magazine’s circulation was beyond the company’s predictions, going from 380,000 copies of the first issue to more than one million a week four months later.[14] It soon challenged The Saturday Evening Post, then the largest-circulation weekly in the country. The magazine’s success stimulated many imitators, such as Look, which was founded a year later in 1937 and ran until 1971.[citation needed]

Luce moved Life into its own building at 19 West 31st Street, a Beaux-Arts building constructed in 1894. Later Life moved its editorial offices to 9 Rockefeller Plaza.[citation needed]

Success[edit]

A co-founder of the new Life magazine, Longwell served as managing editor from 1944 to 1946 and chairman of the board of editors until his retirement in 1954.[8] He was credited for publishing Winston Churchill’s The Second World War and Ernest Hemingway’s The Old Man and the Sea.[15][16][17]

Luce also selected Edward Kramer Thompson, a stringer for Time, as assistant picture editor in 1937. From 1949 to 1961 he was the managing editor, and served as editor-in-chief for nearly a decade, until his retirement in 1970. His influence was significant during the magazine’s heyday, which was roughly from 1936 until the mid-1960s. Thompson was known for the free rein he gave his editors, particularly a «trio of formidable and colorful women: Sally Kirkland, fashion editor; Mary Letherbee, movie editor; and Mary Hamman, modern living editor.»[18]

When the U.S. entered the war in 1941, so did Life. By 1944, of the 40 Time and Life war correspondents, seven were women: Americans Mary Welsh Hemingway, Margaret Bourke-White, Lael Tucker, Peggy Durdin, Shelley Smith Mydans, Annalee Jacoby, and Jacqueline Saix, an Englishwoman. (Saix’s name is often omitted from the list, but she and Welsh are the only women listed as part of the magazine’s team in a Times‘s publisher’s letter, dated May 8, 1944.)[19]

Life backed the war effort each week. In July 1942, Life launched its first art contest for soldiers and drew more than 1,500 entries, submitted by all ranks. Judges sorted out the best and awarded $1,000 in prizes. Life picked 16 for reproduction in the magazine. The National Gallery in Washington, D.C. agreed to put 117 entries on exhibition that summer. Life, also supported the military’s efforts to use artists to document the war. When Congress forbade the armed forces from using government money to fund artists in the field, Life privatized the programs, hiring many of the artists being let go by the Department of War (which would later become the Department of Defense). On December 7, 1960, Life managers later donated many of the works by such artists to the Department of War and its art programs, such as the United States Army Art Program.[20]

Each week during World War II, the magazine brought photographs of the war to Americans; it had photographers from all theaters of war. The magazine was imitated in enemy propaganda using contrasting images of Life and Death.[21]

In August 1942, writing about labor and racial unrest in Detroit, Life warned that «the morale situation is perhaps the worst in the U.S. … It is time for the rest of the country to sit up and take notice. For Detroit can either blow up Hitler or it can blow up the U.S.»[22] Mayor Edward Jeffries was outraged: «I’ll match Detroit’s patriotism against any other city’s in the country. The whole story in Life is scurrilous … I’d just call it a yellow magazine and let it go at that.»[23] The article was considered so dangerous to the war effort that it was censored from copies of the magazine sold outside North America.[24]

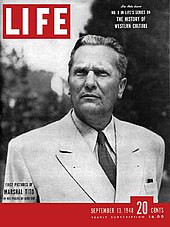

Cover of the September 13, 1948, issue of Life with Marshal Josip Broz Tito

The magazine hired war photographer Robert Capa.[when?] A veteran of Collier’s magazine, Capa accompanied the first wave of the D-Day invasion in Normandy, France, on June 6, 1944, and returned with only a handful of images, many of them out of focus. The magazine wrote in the captions that the photos were fuzzy because Capa’s hands were shaking. He denied it, claiming that the darkroom had ruined his negatives. Later he poked fun at Life by titling his war memoir Slightly Out of Focus (1947). In 1954, Capa was killed after stepping on a landmine, while working for the magazine covering the First Indochina War. Life photographer Bob Landry also went in with the first wave at D-Day, «but all of Landry’s film was lost, and his shoes to boot.»[25]

In a notable mistake, in its final edition just before the 1948 U.S. presidential election, the magazine printed a large photo showing U.S. presidential candidate Thomas E. Dewey and his staff riding across San Francisco, California harbor entitled «Our Next President Rides by Ferryboat over San Francisco Bay». Incumbent President Harry S. Truman won the election.[26] Dewey was expected to win the election, and this mistake was also made by the Chicago Tribune.[citation needed]

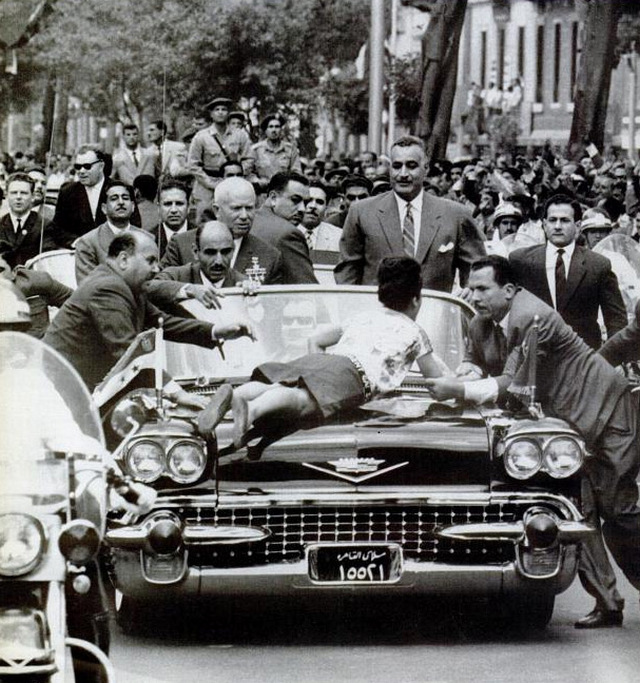

On May 10, 1950, the council of ministers in Cairo banned Life from Egypt forever. All issues on sale were confiscated. No reason was given, but Egyptian officials expressed indignation over the April 10, 1950 story about King Farouk of Egypt, entitled the «Problem King of Egypt». The government considered it insulting to the country.[27]

Life in the 1950s earned a measure of respect by commissioning work from top authors.[citation needed] After Life‘s publication in 1952 of Ernest Hemingway’s The Old Man and the Sea, the magazine contracted with the author for a 4,000-word piece on bullfighting. Hemingway sent the editors a 10,000-word article, following his last visit to Spain in 1959 to cover a series of contests between two top matadors. The article was republished in 1985 as the novella, The Dangerous Summer.[28]

In February 1953, just a few weeks after leaving office, President Harry S. Truman announced that Life magazine would handle all rights to his memoirs. Truman said it was his belief that by 1954 he would be able to speak more fully on subjects pertaining to the role his administration played in world affairs. Truman observed that Life editors had presented other memoirs with great dignity; he added that Life also made the best offer.[citation needed]

For his 1955 Museum of Modern Art traveling exhibition The Family of Man, which was to be seen by nine million visitors worldwide, curator Edward Steichen relied heavily on photographs from Life; 111 of the 503 pictures shown, constituting more than 20% as counted by Abigail Solomon-Godeau.[29] His assistant Wayne Miller entered the magazine’s archive in late 1953 and spent an estimated nine months there. He searched through 3.5 million images, most in the form of original negatives (only in the last years of the war did the picture department start to print contact sheets of all assignments) and submitted to Steichen for selection, many that had not been published in the magazine.[30]

In November 1954, the actress Dorothy Dandridge was the first African-American woman to be featured on the cover of the magazine.[citation needed]

In 1957, R. Gordon Wasson, a vice president at J. P. Morgan, published an article in Life extolling the virtues of magic mushrooms.[31] This prompted Albert Hofmann to isolate psilocybin in 1958 for distribution by Sandoz alongside LSD in the U.S., further raising interest in LSD in the mass media.[32] Following Wasson’s report, Timothy Leary visited Mexico to try out the mushrooms, which were used in traditional religious rituals.[citation needed]

Life‘s motto became[33] «To see Life; to see the world.» The magazine produced many popular science serials, such as The World We Live In and The Epic of Man in the early 1950s. The magazine continued to showcase the work of notable illustrators, such as Alton S. Tobey, whose contributions included the cover for a 1958 series of articles on the history of the Russian Revolution.[citation needed]

However, as the 1950s drew to a close and television became more popular, the magazine was losing readers. In May 1959 it announced plans to reduce its regular news-stand price from 25 cents a copy to 20. With the increase in television sales and viewership, interest in news magazines was waning. Life had to try to create a new form.[citation needed]

1960s and the end of an era[edit]

Henri Huet’s photograph of Thomas Cole featured on the cover of Life, February 11, 1966

A subscription offer from LIFE 1970, the US price was then 19 issues for $2.55

In the 1960s, the magazine was filled with color photos of movie stars, President John F. Kennedy and his family, the war in Vietnam, and the Apollo program. Typical of the magazine’s editorial focus was a long 1964 feature on actress Elizabeth Taylor and her relationship with actor Richard Burton. Journalist Richard Meryman traveled with Taylor to New York, California, and Paris. Life ran a 6,000-word first-person article on the screen star.[citation needed]

«I’m not a ‘sex queen’ or a ‘sex symbol,’ » Taylor said. «I don’t think I want to be one. Sex symbol kind of suggests bathrooms in hotels or something. I do know I’m a movie star and I like being a woman, and I think sex is absolutely gorgeous. But as far as a sex goddess, I don’t worry myself that way… Richard is a very sexy man. He’s got that sort of jungle essence that one can sense… When we look at each other, it’s like our eyes have fingers and they grab ahold…. I think I ended up being the scarlet woman because of my rather puritanical upbringing and beliefs. I couldn’t just have a romance. It had to be a marriage.»[34]

In the 1960s, the magazine featured photographs by Gordon Parks. «The camera is my weapon against the things I dislike about the universe and how I show the beautiful things about the universe,» Parks recalled in 2000. «I didn’t care about Life magazine. I cared about the people,» he said.[35]

The June 1964 Paul Welch Life article entitled «Homosexuality In America» was the first time a national publication reported on gay issues. Life‘s photographer was referred to the gay leather bar in San Francisco called the Tool Box for the article by Hal Call, who had long worked to dispel the myth that all homosexual men were effeminate. The article opened with a two-page spread of the mural of life-size leathermen in the bar, which had been painted by Chuck Arnett in 1962.[36][37] The article described San Francisco as «The Gay Capital of America» and inspired many gay leathermen to move there.[38]

On March 25, 1966, Life featured the drug LSD as its cover story. The drug had attracted attention among the counter culture and was not yet criminalized.[39]

In March 1967, Life won the 1967 National Magazine Award, chosen by the Columbia University Graduate School of Journalism.[citation needed]

Despite the industry’s accolades and its coverage of the U.S. mission to the Moon in 1969, the magazine continued to lose circulation. Time Inc. announced in January 1971 its decision to reduce circulation from 8.5 million to 7 million, in an effort to offset shrinking advertising revenues. The following year, Life cut its circulation further, to 5.5 million beginning with the January 14, 1972 issue. Life was reportedly not losing money, but its costs were rising faster than its profits. Life lost credibility with many readers when it supported author Clifford Irving, whose fraudulent autobiography of Howard Hughes was revealed as a hoax in January 1972. The magazine had purchased serialization rights to Irving’s manuscript.[citation needed]

Industry figures showed that some 96% of Life’s circulation went to mail subscribers, with only 4% coming from the more profitable newsstand sales. Gary Valk was publisher when on December 8, 1972, the magazine announced it would cease publication by the end of the year and lay off hundreds of staff.[citation needed] The weekly Life magazine published its last issue on December 29, 1972.[40]

From 1972 to 1978, Time Inc. published ten Life Special Reports on such themes as «The Spirit of Israel», «Remarkable American Women» and «The Year in Pictures». With a minimum of promotion, these issues sold between 500,000 and 1 million copies at cover prices of up to $2.[citation needed]

1978 monthly (1978–2000)[edit]

Beginning with an October 1978 issue, Life was published as a monthly, with a new, modified logo. Although it remained a familiar red rectangle with the white type, the new version was larger, the lettering was closer together and the box surrounding it was smaller.

Life continued for the next 22 years as a moderately successful[original research?] general-interest, news features magazine. In 1986, it decided to mark its 50th anniversary under the Time Inc. umbrella with a special issue showing every Life cover starting from 1936, which included the issues published during the six-year hiatus in the 1970s. The circulation in this era hovered around the 1.5 million-circulation mark. The cover price in 1986 was $2.50 (equivalent to $6.18 in 2021). The publisher at the time was Charles Whittingham; the editor was Philip Kunhardt. In 1991 Life sent correspondents to the first Gulf War and published special issues of coverage. Four issues of this weekly, Life in Time of War, were published during the first Gulf War.

The magazine struggled financially and, in February 1993, Life announced the magazine would be printed on smaller pages starting with its July issue. This issue also featured the return of the original Life logo.

Life reduced advertising prices by 34%[when?] in a bid to make the monthly publication more appealing to advertisers. The magazine reduced its circulation guarantee for advertisers by 12% in July 1993 to 1.5 million copies from the current 1.7 million. The publishers in this era were Nora McAniff and Edward McCarrick, while Daniel Okrent was the editor. Life for the first time was the same trim size as its longtime Time Inc. sister publication, Fortune.

Though experiencing financial trouble, in 1999 the magazine still made news by compiling lists to round out the 20th century. Life editors ranked their «Most Important Events of the Millennium.» This list has been criticized for being overly focused on Western achievements.[citation needed] The Chinese, for example, had invented type four centuries before Johannes Gutenberg, but with thousands of ideograms, found its use impractical. Life also published a list of the «100 Most Important People of the Millennium.» This list, too, was criticized for focusing on the West. Thomas Edison’s number one ranking was challenged since critics believed other inventions, such as the Internal combustion engine, the automobile, and electricity-making machines, for example, had greater effects on society than Edison’s. The top 100 list was criticized for mixing world-famous names, such as Isaac Newton, Albert Einstein, Louis Pasteur, and Leonardo da Vinci, with figures largely unknown outside of the United States (18 Americans compared to 13 Italian and French, and 11 English).[citation needed]

In March 2000, Time Inc. announced it would cease regular publication of Life with the May issue.

«It’s a sad day for us here,» Don Logan, chairman and chief executive of Time Inc., told CNN.com. «It was still in the black,» he said, noting that Life was increasingly spending more to maintain its monthly circulation level of approximately 1.5 million. «Life was a general interest magazine and since its reincarnation, it had always struggled to find its identity, to find its position in the marketplace,» Logan said.[41]

The magazine’s last issue featured a human interest story. In 1936, its first issue under Henry Luce featured a baby named George Story, with the headline «Life Begins»; over the years the magazine had published updates about the course of Story’s life as he married, had children, and pursued a career as a journalist. After Time announced its pending closure in March, George Story happened to die of heart failure on April 4, 2000. The last issue of Life was titled «A Life Ends», featuring his story and how it had intertwined with the magazine over the years.[42]

For Life subscribers, remaining subscriptions were honored with other Time Inc. magazines, such as Time. In January 2001, these subscribers received a special, Life-sized format of «The Year in Pictures» edition of Time magazine. It was a Life issue disguised under a Time logo on the front. (Newsstand copies of this edition were published under the Life imprint.)

While citing poor advertising sales and a difficult climate for selling magazine subscriptions, Time Inc. executives said a key reason for closing the title in 2000 was to divert resources to the company’s other magazine launches that year, such as Real Simple. Later that year, its parent company, Time Warner, struck a deal with the Tribune Company for Times Mirror magazines, which included Golf, Ski, Skiing, Field & Stream, and Yachting. AOL and Time Warner announced a $184 billion merger, the largest corporate merger in history, which was finalized in January 2001.[43]

In 2001, Time Warner began publishing special newsstand «megazine» issues of Life, on topics such as the September 11 attacks in 2001 and the Holy Land. These issues, which were printed on thicker paper, were more like softcover books than magazines.[clarification needed]

1990s online presence[edit]

Life‘s online presence began in the 1990s[44] as part of the Pathfinder.com network. The standalone Life.com site was launched on March 31, 2009, and closed on January 30, 2012. Life.com was developed by Andrew Blau and Bill Shapiro, the same team who launched the weekly newspaper supplement. While the archive of Life, known as the Life Picture Collection, was substantial, they searched for a partner who could provide significant contemporary photography. They approached Getty Images, the world’s largest licensor of photography. The site, a joint venture between Getty Images and Life magazine, offered millions of photographs from their combined collections.[45] On the 50th anniversary of the night Marilyn Monroe sang «Happy Birthday» to John F. Kennedy, Life.com presented Bill Ray’s iconic portrait of the actress, along with other rare photos.

2013 movie release[edit]

The film, The Secret Life of Walter Mitty (2013), starring Ben Stiller and Kristen Wiig, portrays Life as it transitioned from printed material toward having only an online presence.[46] Life.com later became a redirect to a small photo channel on Time.com. Life.com also maintains Tumblr[47] and Twitter[48] accounts and a presence on Instagram.

2004 supplement (2004–2007)[edit]

Beginning in October 2004, Life was revived for a second time. It resumed weekly publication as a free supplement to U.S. newspapers, competing for the first time with the two industry heavyweights, Parade and USA Weekend. At its launch, it was distributed with more than 60 newspapers with a combined circulation of approximately 12 million. Among the newspapers to carry Life were the Washington Post, New York Daily News, Los Angeles Times, Chicago Tribune, Denver Post, and St. Louis Post-Dispatch. Time Inc. made deals with several major newspaper publishers to carry the Life supplement, including Knight Ridder and the McClatchy Company. The launch of Life as a weekly newspaper supplement was conceived by Andrew Blau, who served as the President of Life. Bill Shapiro was the founding editor of the weekly supplement.

This version of Life retained its trademark logo but sported a new cover motto, «America’s Weekend Magazine.» It measured 9½ x 11½ inches and was printed on glossy paper in full color. On September 15, 2006, Life was 19 pages of editorial content. The editorial content contained one full-page photo, of actress Julia Louis-Dreyfus, and one three-page, seven-photo essay, of Kaiju Big Battel. On March 24, 2007, Time Inc. announced that it would fold the magazine as of April 20, 2007, although it would keep the web site.[2][4]

2008: Google partnership[edit]

On November 18, 2008, Google began hosting an archive of the magazine’s photographs, as part of a joint effort with Life.[49] Many images in this archive had never been published in the magazine.[50] The archive of over six million photographs from Life is also available through Google Cultural Institute, allowing for users to create collections, and is accessible through Google image search. The full archive of the issues of the main run (1936–1972) is available through Google Book Search.[51]

2016 and later: special issues[edit]

Special editions of Life are published on notable occasions, such as a Bob Dylan edition on the occasion of his winning the Nobel Prize in Literature, in 2016, Paul at 75, in 2017, and «Life» Explores: The Roaring ’20s in 2020.[52] Life is now published by the IAC’s subsidiary Dotdash Meredith.

Today[edit]

Life is currently owned by Dotdash Meredith, which own most of former Time Inc. assets.

Contributors[edit]

Notable contributors have included:

- John Kendrick Bangs (editor, writer)

- Dominic Behan (writer)

Photojournalists:

- Harry Benson

- Berry Berenson

- Walter Bosshard

- Margaret Bourke-White

- Brian Brake

- Larry Burrows

- David Burnett

- David Douglas Duncan

- Robert Capa

- Henri Cartier-Bresson

- Loomis Dean

- John Dominis

- Alfred Eisenstaedt

- Eliot Elisofon

- Bill Eppridge

- Andreas Feininger

- Ron Galella

- Alfred Gescheidt

- Bob Gomel

- Allan Grant

- Dirck Halstead

- Marie Hansen

- Bernard Hoffman

- Henri Huet

- Isaac Kitrosser

- Peter B. Martin

- Hansel Mieth

- Lee Miller

- Gjon Mili

- Ralph Morse

- Carl Mydans

- Gordon Parks

- John Phillips

- Bill Ray

- Co Rentmeester

- Paul Schutzer

- Art Shay

- George Silk

- George Strock

- W. Eugene Smith

- Peter Stackpole

- Pete Souza

- Edward K. Thompson (M. editor 1949–61; editor 1961–70)

- John Vachon

- Jeff Vespa (and editor)

- Leigh Wiener

- Tony Zappone (Europe edition)

- John G. Zimmerman

- Lalaine Madrigal

Film critics:

- Brad Darrach

- Wheeler Winston Dixon

Fashion:

- Howell Conant (fashion photographer)

- Sally Kirkland (editor/fashion)

- Clay Felker (sportswriter, founder of New York magazine)

Photographers:

- John Florea

- Henry Grossman

- Philippe Halsman

- Dorothea Lange

- Nina Leen

- Mark Shaw

- André Weinfeld (portrait)

- Edward Steichen (portrait)

Illustrators:

- Charles Dana Gibson

- Lejaren Hiller, Sr.

- Mary Hamman (modern living editor)

- Jane Howard (journalist correspondent)

- Will Lang Jr. (bureau chief)

- Henry Luce (publisher, editor-in-chief)

- Richard Edes Harrison (cartographer)

- Gerald Moore (reporter)

Writers:

- Normand Poirier